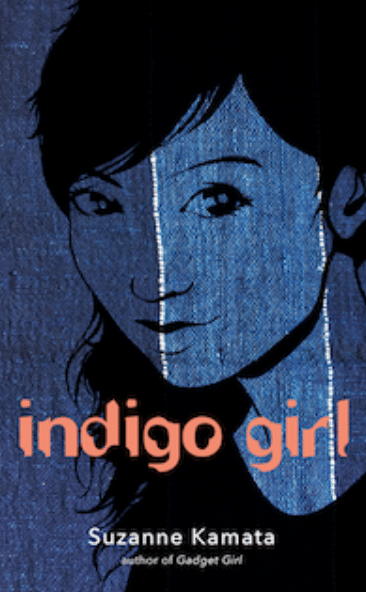

Indigo Girl

- Fiction

- Set in America and Japan

Keywords: disability, farming, family, coming-of-age, identity

Fifteen-year-old Aiko Cassidy, a bicultural girl with cerebral palsy, grew up in Michigan with her single mother. For as long as she could remember, it was just the two of them. When a new stepfather and a baby half sister enter her life, she finds herself on the margins. Having recently come into contact with her biological father, she is invited to spend the summer with his indigo-growing family in a small Japanese farming village. Aiko thinks she just might fit in better in Japan. If nothing else, she figures the trip will inspire her manga story, Gadget Girl.

However, Aiko’s stay in Japan is not quite the easygoing vacation that she expected. Her grandmother is openly hostile toward her, and she soon learns of painful family secrets that have been buried for years. Even so, she takes pleasure in meeting new friends. She is drawn to Taiga, the figure skater who shows her the power of persistence against self-doubt. Sora is a fellow manga enthusiast who introduces Aiko to a wide circle of like-minded artists. And then there is Kotaro, a refugee from the recent devastating earthquake in northeastern Japan.

As she gets to know her biological father and the story of his break with her mother, Aiko begins to rethink the meaning of family and her own place in the world.

Indigo Girl is filled with examples of contemporary life in Japan, many of which are explained below so that students can better understand the social and cultural contexts that are integral to the story.

Homes in Japan: Many homes in Japan today are a mix of contemporary and traditional architecture and interior design. When you enter a Japanese house, remove your shoes in the genkan (foyer) and then step up to the main floor, where you are given slippers. It is not uncommon to have tatami mat rooms, as in the farmhouse in this story. Slippers are removed before entering a tatami room. In these rooms, you sit on the floor, typically on your knees with your legs crossed under you at the ankles. Boys and men often sit cross-legged. Older Japanese often use small, raised seats to take the pressure off their legs.

Breakfast: Aiko is surprised at the type of breakfast she receives at the farmhouse. A typical Japanese breakfast is rice, soup, salad, and perhaps some fish. “Western style” includes fried eggs, ham, salad, and thick slice of white toast. Japanese also will eat leftovers from the night before, such as curry rice, for breakfast. Tea and/or coffee is also served.

Bathrooms and Toilets: The toilet and room for bathing are separate in Japan. You always take off your house slippers and put on toilet slippers when entering the room with the toilet. t is not uncommon to locate the washing machine next to the room for bathing. For bathing, you enter a separate room where there is a shower and a bathtub. You must never get into that bathtub without showering first. After scrubbing with soap and rinsing off, you lower yourself into the tub for a nice relaxing soak in very hot water. Several people may use the same bath, so it is important to keep the water clean and hot. (Do not add cold water to the bath!)

Butsudan (Buddhist altar): Homes often have what the author refers to as a shrine. This is a butsudan, a Buddhist altar where prayers and offerings are made for deceased family members. Typically, the butsudan will house a statue or painting of the Buddha or a Buddhist deity. Memorial tablets and photos of the deceased are placed upon the altar, and flowers and incense typically placed in front of the photographs. Food and/or tea may also be placed there as an offering. Typically, upon approaching the altar, you light a stick of incense and put it in its holder, strike a small mallet against a bowl-shaped bell, and then offer prayers to the deceased.

The Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995: This national disaster is referred to several times in the book. Also called the Kobe earthquake or the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake, this huge earthquake (7.3 on the Richter scale) occurred at 5:46 a.m. Japan time on January 17, 1995. It struck the Hanshin area of Japan, Japan’s second largest urban area, which includes the cities of Osaka and Kobe. The epicenter was located beneath the northern end of Awaji Island. An estimated 6,400 people were killed, 40,000 injured, and over 240,000 homes damaged overall, with the city of Kobe being the hardest hit (4,571 fatalities, over 14,000 injured, over 120,000 damaged structures). Roads and bridges were twisted and broken, and traditional houses with heavy roof tiles became death traps for many families. [source: https://www.britannica.com/event/Kobe-earthquake-of-1995]

3.11: This triple disaster is also referred to in the book, and is the reason for why Aiko’s new friend, Taiga, and a second character, Kotaro, are both refugees from Tōhoku. At 9:46 p.m. on Friday, March 3, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck in the Pacific Ocean, east of Sendai in the Tōhoku region of northern Honshu. The rare magnitude 9.0 earthquake lasted three minutes and moved the main island of Honshu a few meters east, with the local coastline subsiding half a meter. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan. The 15-meter tsunami that followed was horrific in its size and speed, overwhelming entire neighborhoods while people attempted to flee. Around 19,500 people were confirmed dead, over a million buildings collapsed or were destroyed. The tsunami caused the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, primarily the partial meltdowns of three of the fuel rods in three of its reactors. The release of radiation that followed resulted in the evacuation of over 100,000 people. [source: https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident.aspx]

Half-lion half-dog statues: Aiko passes a local shrine (p. 39). The half-lion half-dog statues are Chinese lion dogs (komainu), which often appear as guardian figures at or near the entrance to shrines or temples. The “red gate” is a torii, which is a tall gate under which you pass when you enter the grounds of a shrine. The main building within a Shinto shrine houses the nature spirit of the shrine. The image below is a large torii at the Fushimi Inari Taisha (Shrine) in Kyoto.

Arranged marriages: These are not quite what Americans would think. In modern Japan, a family would approach a matchmaker about finding a potential marriage partner for their son or daughter. The matchmaker would provide some photos and descriptions of various possibilities, and then the son or daughter would decide whether they were interested in meeting one of these people. If the couple hit it off, they would continue to date and might become engaged. In the past, an arranged marriage might have been more the decision of the family heads rather than between the couple (as was the case with the grandmother in the story). In contemporary Japan, couples also meet the same way that they do in the U.S., without using the matchmaker.

Adoption: Also mentioned in the book is the adoption of a man into a woman’s family. The type of adoption that Americans are familiar with is not the custom in Japan. Rather, when a family does not have a male heir to pass on the family name or take up the family occupation, a young man who marries the eldest daughter of the house will often legally adopt the girl’s family name. This type of adoption is centuries old and was used to maintain a male head of a business or household. The practice still occurs today.

Laundry: There are both washers and dryers in Japan, but typically only washers are used. Laundry is then hung up to dry indoors or outside in the open air. There are all sorts of poles and other articles used for hanging laundry from balconies or in the garden.

Shikoku pilgrimage: the pilgrimage site mentioned on page 59 is one of 88 Buddhist temples that are part of the Shikoku pilgrimage. Devoted pilgrims usually wear special clothing, but one can also walk part or all of the route without doing so. The full route, if walked in its entirety, can take several months.

Otani yaki (Otani ware): Japan has many regional specialties, such as variations in teas, ceramics, cloth, and items made of wood. Otani pottery, mentioned on page 67, is a representative ceramic of Shikoku.

Treatment of Guests: Aiko is uncomfortable with the way her family hovers over her and prevents her from going about by herself. But in Japan, hospitality is very important, and that means making sure the guest is not inconvenienced or has to go anywhere alone. To an American, this can seem stifling; to a Japanese, this is just good manners.

Bowing: Bowing is a very important sign of respect in Japan. You keep your back straight as you bow, head slightly lowered, and hands either at the side or crossed in front of you. There are even different levels of bowing; a teacher or boss receives a deeper bow than a colleague at work or a casual acquaintance, for example. Quick shallow bows are common when acquaintances meet in the street.

Japanese Words: there are too many Japanese words to include in this essay but a few common ones that students enjoy learning include:

Ohayō gozaimasu [oHIO_GO_ZAI_MAH_suh] Good morning (said before 11:00 a.m.)

Konnichi wa [KOH_KNEE_CHEE_wah] Good day (said after 11:00 a.m. and before evening)

Gomen nasai [go_MEN_NAH_sigh_ee] Excuse me or an apology (this phrase typically of western Japan)

Arigatoo gozaimasu [ah_REE_GAH_toe_ go_ZAI_MAH_suh] thank you

Hai [HA_ee; pronounced like the greeting “hi” in English] yes; also used as a response to a teacher asking if you are present

Tadaima [tah_DIE_EE_mah] I’m home! I’m back! I’ve just arrived!

Author: Brenda G. Jordan, former University of Pittsburgh NCTA Director

2025

As a fiber artist and educator, I was initially interested in this book because of the word “indigo” in the title. The summary drew me in further when I learned that the central character spends time in Japan on her father’s indigo farm. I found this book to be a wonderful read that I highly recommend for teachers working with students aged twelve to sixteen, or in grades 7 through 11. The central character, Aiko Cassidy, is of American and Japanese descent, and she has cerebral palsy. Her mother’s recent marriage and Aiko’s new roles as stepdaughter and big sister to a half-sister, Esme, have left her questioning her place in her family. As the story opens, Aiko’s sense of belonging is further challenged by a summer trip to Japan to see her biological father and his family, whom she has never met.

Readers of Suzanne Kamata’s works may already be familiar with Aiko from Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible. Set in Paris, Gadget Girl addresses many of the same themes as Indigo Girl: the search for self-identity, the complexities of young love, and a desire for acceptance. I hesitate to call Indigo Girl a sequel to Gadget Girl as it stands on its own. Because of Aiko’s age, her conflicted feelings about her biological father, and the love she feels for her stepfather, this text is better suited to students of high-school age and may, as such, engage a wider audience than Gadget Girl. In schools where Social/Emotional Learning is a focus, this text could be an important resource. Students may be reluctant to engage in sensitive topics that suggest that they are feeling alienated, lost, or unsure of their place among peers and family. But through Aiko, students could discuss these concerns without having to personalize their comments. Aiko’s struggles may also provide a way for students to make connections to their own lives and feel more comfortable in discussing them.

Kamata skillfully weaves issues of identity and culture throughout Aiko’s story. Having grown up in the U.S., Aiko is immediately aware that she is perceived differently in Japan, as a biracial young woman with cerebral palsy. The author draws upon her own experiences in Japan of raising a biracial child with physical disabilities. In her personal blog, Kamata notes that many of the resources available to American students with disabilities are not available to students with mental and physical challenges in Japan. When Aiko is introduced to the entire student body of her stepbrother’s school, she not only has to overcome the humiliation of having to walk to the podium, but she is introduced as a cousin to conceal her true relationship to the family. Kamata addresses these topics in an open and honest manner, neither criticizing Japanese cultural norms nor suggesting any superiority in the American way of doing things. Rather, through Kamata’s use of the first-person narrative, we see what Aiko thinks about the differences between her American family and her Japanese family, and ultimately, she is able to appreciate both viewpoints.

This text would be a great summer read for students who are part of a Social Studies course that addresses the history and culture of Asia, a Sociology course, or Psychology course. It is my experience that many students do not believe they have a culture but, rather, that their experience is normal or standard, and that anything that deviates from it is strange. To explore the influence of culture, students could be asked to write a paper focusing on a ritual that is part of their culture, but from the viewpoint of an outsider. This mirrors Aiko’s experience of attending school with her stepbrother and recalls the questions Japanese students ask Aiko, which reflect some misunderstanding of what American teenagers can and cannot do—providing rich topics for discussion. Horace Miner’s influential 1956 essay “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” would be another interesting resource to supplement the reading of this text. Additionally, students could research information about the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) to learn more about this important piece of legislation and to debate issues surrounding the notion of “equal opportunity” and how this is addressed in other cultures.

Aiko’s biological father is an indigo farmer, and she begins to help him with the annual harvest. The work is done by hand over many months and is labor-intensive, requiring near constant attention as well as specialized knowledge. The family is one of the few that still creates the stunning natural blue dye in this manner. Aiko realizes that despite her stepbrother’s love of robotics, he feels a sense of duty to continue in the steps of his father and grandfather, who was regarded as a Living National Treasure. Here too, Kamata addresses opposing cultural norms in a direct and engaging manner through conversations between Aiko and her family, creating an opportunity in the classroom for dialogue about self-direction versus familial obligation.

Aiko’s experiences with indigo farming could be used by a history or literature teacher working with a teacher in the Sciences to explore how the plant is grown and harvested. Although indigo is grown in many places throughout the world, the way the leaves are processed to yield a wide range of blue hues is unique to each culture, based on climate and the growing season. A contemporary issue affecting famers of all crops is climate change. Considering the intensive physical labor and time required to yield a small amount of indigo dye, it is no wonder that few farmers grow it today. That said, a revival of natural dyes is underway as the world becomes more aware of the impact of synthetic dyes on the environment. This issue would be interesting for students in Family and Consumer Science classes to research as they study fibers, fabric, and the role of fashion in the destruction of the environment.

Teachers of American History could extend the study of indigo to their classroom as well. While the name Elizabeth (Eliza) Lucas Pickney is not well known outside of Charleston, South Carolina, in the eighteenth century, Pickney transformed indigo into an important cash crop exported throughout the world. Finally, studio art teachers can use indigo dye to introduce students to shibori, a Japanese way of binding, tying, stitching and wrapping fabric before dying to create pattern on cloth (a type of sophisticated tie-dyeing). Shibori has become very popular and is used today in contemporary ways to add color to all manner of clothing and textile pieces such as pillows, wall hangings, and kitchenware.

Another strong STEAM connection that could be addressed through the text is the effect of natural disasters on the people of Japan. Through Taiga, who became a refugee after an earthquake, and through the tsunami in Tohoku, readers are made aware of the devastating impact of natural disasters on a human scale. The increasing severity of weather and natural disasters could be addressed in a variety of ways, through the study of global warming and climate change.

Aiko’s desire to help those affected by the tsunami is a thread that runs throughout the text, and she seeks ways to help others in a meaningful way. Significantly, Aiko’s gift for drawing anime enables her to connect with another person who is in need of help, and as the text draws to a close, the reader can see that by sharing her art, Aiko may have found a way to help her family as well. Aiko’s love of anime and manga are a way to connect with her peers; by encouraging students to look at manga, anime, and graphic novels, teachers of studio art, art history, and literature will discover additional ways for students to interact with the text.

Ultimately, this novel has multiple applications for teachers in all disciplines. It is an engaging story, and Aiko is a character students will easily identify with. Although this book stands on its own, teachers in middle school may find it worthwhile to introduce students to Aiko via Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible and team up with a colleague at high school to reintroduce students to Aiko as a more mature young woman in Indigo Girl.

Recommended Teaching Resources

- Americans with Disabilities Act. 1990. ADA.gov

- Kamata, Suzanne. Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible. GemmaMedia, 2013.

- Miner, Horace. “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema.” American Anthropologist 58, no.3 (1956): 503–507.

Author: Kachina Leigh, 10–12 Studio Art and Art History Teacher, Muhlenberg High School, Reading, Pennsylvania

2021

Fill out the online form to view NCTA webinar with author Suzanne Kamata