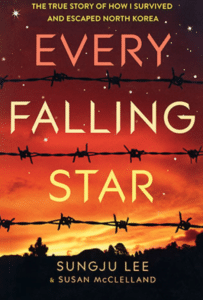

Every Falling Star

- Non-fiction

- Set in North Korea

Keywords: politics, survival, friendship, resilience

A timely and gripping autobiographical account of a teenage boy in North Korea. An authentic view of the “inside” of North Korea, and the reality of the life of ordinary citizens living under a regime of severe political constraints that has isolated itself from the world. Students will gain a better understanding both of why some North Korean people support the regime as well as why others try to escape. Excellent non-fiction read for high school students.

Theme: Migration

The United States is a nation of immigrants. Indigenous communities also have stories of migration, displacement, or first meetings. Migration stories are often about hardship, injustice, and intense suffering, and this is certainly true for North Koreans who have fled the regime and settled elsewhere. As author Sungju Lee (pronounced: SUHNG-joo LEE) explains in this memoir, he hopes to change the conditions that created the injustice and suffering by telling his story. Here is some background information to help you and your students better understand the story.

Genre: Refugee Memoir

Sungju Lee’s family is one of many who fled North Korea to escape persecution and famine. They are part of a massive flow of people around the world who are displaced by circumstances and must go on dangerous journeys across borders to survive. Sungju Lee’s story is a refugee memoir, told by people who witnessed or experienced refugee migration firsthand, or who were part of refugee communities.

Dogs in Korea

In his early years, Sungju and his family lived a comfortable life in Pyongyang (pronounced: PYUHNG-yahng) North Korea. Their dog, Bo Cho, was a Pungsan (or Poongsan; pronounced: POONG-sahn), one of three dog breeds native to Korea. Originally from North Korea, Pungsan were raised as hunting dogs. The Sapsali (romanized as Sapsaree; pronounced: sahp-SAH-lee) dog breed is also native to Korea. It was believed that that Sapsali could hunt ghosts and chase away spirits.

The Jindo (Jindo gae; pronounced: chin-DOH geh) is said to originate from Jindo Island. The famous Jindo dog statue was inspired by the story

of a Jindo that, after being adopted by a family living 180 miles away from her previous home, escaped and made her way back to her family on Jindo Island. Jindo dogs are thought to be very loyal, brave, and protective of their humans.

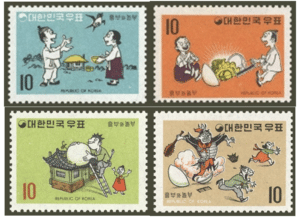

Korean Folktales: The Legend of the Brothers Hungbu and Nolbu

The folktale of brothers Hungbu (pronounced: HUUNG-boo) and Nolbu (pronounced: DOHL-boo) is known throughout the Korean peninsula. It was even retold in a 1970s South Korean stamp series (see images below). As the story goes, Hungbu and his wife are kind and generous people. Though they are poor, they maintain their good natures. One day they find a sparrow with an injured leg, and they nurse the injured sparrow back to health. The sparrow then returns the next spring with a gourd seed, which the couple plants. They harvest the ripened gourds to find wealth beyond their dreams. It is a reward from the Sparrow King for their good deed.

Though Nolbu is already rich after hoarding the family wealth and chasing Hungbu’s family from their land, Nolbu is envious of his brother’s newfound wealth and demands to know the source. Hungbu tells him the entire story. Not satisfied until they have more wealth than Hungbu, Nolbu and his wife find a sparrow. They injure its leg on purpose in order to nurse it back to health. The next spring, the sparrow brings them an enchanted gourd seed. But instead of more wealth, they receive tokkebi (goblins; pronounced: TOH-KEH-bee), who punish them for their bad deeds and take away all they have.

Hungbu, who is still generous and humble, takes in Nolbu’s family. Nolbu eventually becomes a kinder person, thanks to the example of his younger brother, Hungbu.

Folktales endure through time and generations in part because they can be adapted to new lessons. The story of Hungbu and Nolbu teaches that what goes around comes around. It also teaches that everyone matters in a community, and people with more wealth are responsible for the welfare of people who have less. Yet another lesson is that people should be kind to one another and to their companions in nature, such as the bird who is injured in the story. In Sungju’s grandfather’s version, the story teaches about the relationship between North and South Korea. The countries are like estranged brothers.

The Korean People’s Army of North Korea

Sungju Lee’s father was a high-ranking military officer in the North Korean Army (officially known as the Korean People’s Army), and his mother was a schoolteacher. Like many North Korean children, Sungju dreamed of becoming a soldier in the army. Military service is universal and mandatory in North Korea—for both men and women. Service for men typically lasts ten years; for women, until they are twenty-three.

Youth Leagues

In North Korea, the Youth League and the Young Pioneers are similar to Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts in the United States, but participation is universal and compulsory. All North Korean children are required to join the Korean Children’s Union from ages seven to thirteen, and they must join the Youth League from ages fourteen to thirty. Children in the KCU are required to perform labor and produce certain quotas in areas such as farming, construction, and collecting materials for their school. Failure to do so results in a cash penalty.

The image below is a Victory Day Parade with members of the Youth League (Kimilsungist-Kimjongilist Youth League) being cheered on by Korean Children’s Union members (Young Pioneers) along the sidewalk.

The Legacy of Kim Il-Sung

On July 8, 1994, Kim Il-Sung (pronounced: KEEM ILL-suhng), founder of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, died and the nation went into mourning. People feared they would be punished if they didn’t weep loudly enough. It was also a year of disasters in North Korea, including flooding, drought, widespread famine, and economic collapse. During this period, Lee’s family, who had been in good standing with the Party and the military, were ruthlessly persecuted. Many other families also fell victim to political changes and social turbulence.

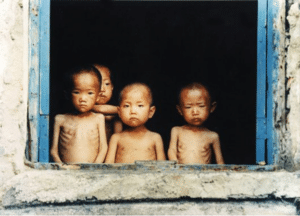

Famine

Before the 1990s, many North Koreans enjoyed a decent standard of living, with universal employment, furnished housing with utilities, free education, and ample time for leisure activities (arts, sports, culture). Beginning in the mid-1990s, anyone who was not a Korean Workers’ Party member in good standing was in danger of losing everything in the economic crisis. At present, it is estimated that one in four North Korean children suffers from malnutrition (Source: Liberty in North Korea, libertyinnorthkorea.org).

Sungju witnesses increasingly dire famine conditions in the town of Gyeongseong (pronounced: KYUHNG-suhng). As rations become scarce, the Lees forage for anything edible, but Sungju knows that they are starving, along with everyone else in Gyeongseong. The search for resources drives Sungju’s father to leave the family and cross into China. Sungju’s mother also leaves in search of food, never to return. Sungju survives by eating a ration of salt and water each day until he finally leaves the house to go to the home of his friend Young-Bum (pronounced: YUHNG-buhm) for help. Without this help, he believes he would have died, like so many people in Gyeongseong.

Social Control

In North Korea, family punishment is a common practice. If one person is in trouble with the authorities for even a slight infraction such as expressing dissent, the entire family can be sanctioned, with punishment including jail or executions. For Sungju’s father’s infraction, the entire family was punished. North Koreans who have left the country take precautions not to provide any information that might endanger family members who may still be in North Korea.

People who are caught trying to escape are punished with jail time or execution. As a child in Gyeongseong, Sungju and his classmates are marched to the public execution of a man and woman who were accused of stealing equipment and crossing into China. They were branded as “traitors.”

Dreams and Omens

For Sungju, omens and dreams are crucial sources of information in his chaotic life on the streets. After seeing a falling star or a bird on an unusual flight path, Sungju finds that his life takes unexpected turns. Some of these images are prescient: he sees a person in his dream and later learns of their death.

Myths and legends also figure into young Sungju’s understanding of the events in North Korea. Living with his kkotjebi group (see below; pronounced: GOH-CHEH-bee), the slightest mistake or bad luck can make the difference between life and death, and Sungju is careful of the shan-shin-ryong-nim (benevolent cave-dwelling spirits; pronounced: SAHN-SHILL-YUHNG-neem) and ru-ryeong (vengeful ghosts; pronounced: YOO-lyuhng).

Omens and dreams have a special significance in Korean culture. Symbolism can involve things like animals, colors, times of day, or seasons. Dreams can be portents when they include family or ancestors.

The seven brightest stars of the Big Dipper constellation are called the Chilseong (Seven Stars; pronounced: CHILL-suhng). In Korean mythology, the stars were the home of the mythical Jade Emperor.

Orphan Gangs: The Kkotjebi

Sungju, Young-Bum, Chul-Ho (pronounced: CHUH-loh), and the other orphaned boys become a second family by joining a kkotjebi. Joining a kkotjebi gang is how most children survive after losing their families to famine or displacement. The gang members work together to steal from the markets, but some also work with merchants to provide protection. They might also fight with rival kkotjebi gangs over territory or access. They could work with another gang and steal for them in exchange for food, security, fighting skills, and so on, as Sungju’s kkotjebi worked with Big Brother’s gang in the Pohang (pronounced: POH-ahng) market. Sungju and his group of kkotjebi get into a fight and lose one of their brothers.

Though its members are all children, the kkotjebi functions like a family with its own traditions. They care for the sick among their ranks and hold funeral rites when a member dies.

Currency: Won

Among the many adjustments for North Korean refugees in South Korea is a currency system with the same name, won, but with a very different scale. Five North Korean won is equivalent to 0.006 USD, or about half of one cent (in 2020, 1 USD = 900 North Korean won or 1,191 South Korean won). The five-won note is the smallest denomination of paper currency in circulation in North Korea.

Authors:

Hye-Seung (Theresa) Kang, PhD, Director, Indiana University NCTA National Coordinating Site; Associate Director, East Asian Studies Center

Perry Miller, PhD, EdD Student in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Indiana University; Senior Lecturer, Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Ohio State University

2021

Appropriate Age/Grade Level

Every Falling Star is most appropriate for high school students, grades 9 and up.

Contextualizing Curricular Connections

Every Falling Star is a young teen memoir set in North Korea. Many books tell true stories of how adults escape from North Korea—such as the autobiography Aquariums of Pyongyang by Kang Chol-Hwan and Nothing to Envy by journalist Barbara Demick—but this is the first to offer the perspective of a young teen living on the streets of North Korea. While other books focus on the main character’s survival as a refugee, Every Falling Star concentrates on the boy’s survival within the Hermit Kingdom. It begins with twelve-year-old Sungju Lee (pronounced: SUHNG-joo LEE)living with his family in Pyongyang, then traces the next five years. When Sungju’s father falls out of favor with the regime, the family is forced to flee the capital for more remote areas of North Korea, where a famine is raging. His parents leave in search of food, and when they do not return, Sungju forms a street gang to survive. Years later, he is reunited with his father in South Korea.

Common Core Standards

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.9-10.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.9-10.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.9-10.3: Analyze in detail a series of events described in a text; determine whether earlier events caused later ones or simply preceded them. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.1: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.2: Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

CCSS.ELA-READING LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.3: Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-SPEAKING AND LISTENING.SL.9-12.1: Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 9–10 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-WRITING STANDARDS FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY.R.9-12.7: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-WRITING STANDARDS FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY.WHST.9-12.10: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for reflection and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Literary Themes

Survival, state control, family, street life, gangs, drugs, theft, violence, smuggling, connection, disconnection

Concepts and Entry Points: High School (9–12)

Each of the following concepts can reinforce understanding, open discussion, or serve as a jumping-off point into a portion of the book or research connected to the novel.

Korean War: war that was fought in 1950–1953 on the Korean peninsula. The north of Korea was supported by the Soviet Union, and the south was supported by the United Nations, including the United States. Ultimately, the war did not officially end but was paused on July 27,1953, with an armistice agreement that remains in effect today.

DMZ: Demilitarized Zone. After World War II, the Soviet Union accepted Japanese surrender north of the 38th parallel and controlled this land, while the United States accepted Japanese surrender and control south of this line. Once the Cold War began, different leaders and ideologies took hold in each region, and these differences led to the Korean War. While the war moved the boundary between 1950 and 1953, the conflict ended where it started, and the DMZ continues to divide the Korean peninsula today. It is approximately 1.2 miles wide and 150 miles long.[1]

Juche (pronounced: jew-shay): a North Korean term meaning “self-reliance,” used by the communist party to emphasize a sense of unique “North Korea-ness.” People, propaganda, and household items (for example, portraits of the leader) are imbued with juche to demonstrate true commitment and loyalty to the North Korean nation and its leaders.

Pyongyang (pronounced: PYUHNG-yahng): the capital of North Korea, where people who have the most commitment to the North Korean communist party live (for example, party and military leaders). The quality of life in Pyongyang is higher than elsewhere in the country in terms of housing, food, and education. By North Korean party standards, life here is presented as ideal and serves as the model for the rest of North Korea, though most North Koreans don’t enjoy this standard and know that it is unachievable.

Kotjebi (pronounced: GOH-CHEH-bee): this term refers to homeless people, typically street children, who often live together in gangs. These gangs serve as surrogate families for children whose parents have died or left town to search for opportunities (either within North Korea or across the border in China).

Great Famine: a famine that occurred in 1995–1999, under Kim Jong Il. Approximately 3–5% of the North Korean population (600,000–1,000,000 people) died during this time.[2] As North Koreans were expected to demonstrate juche, or self-reliance and tenacity, this is also known as the Arduous March or the March of Suffering, which was portrayed as parallel to the experience of Kim Jong Il’s hundred-day march in opposition to Japan’s occupation in the 1930s.

Guiding Questions

Describe the differences between Sungju’s life in Pyongyang and the life of Gyeong-seong (pronounced: KYUHNG-suhng).

- Sungju’s father never tells him directly why they had to leave Pyongyang, but he discovers the truth in many ways. Provide at least three specific examples from the book (for example, conversations with other boys, observations he makes, things his parents say) that give him clues about why they had to leave the capital city.

- Sungju loses his education when he is forced to move to the countryside. Though, arguably, his greatest education comes from this transition. Describe the process that Sungju undergoes as he shifts from life as a Pyongyang youth full of juche to a kotjebi orphan surviving on the street. What does he have to learn and unlearn?

- Discuss the term juche and the role it plays in North Korean society vs. the role it plays in Sungju’s story.

- What global issues in Sungju’s story transcend borders? What do the people of North Korea face that other people in the world also face, regardless of their government or geographic boundaries.

Suggested Learning Activities

Research

Students can extend their learning through one or more of the following research topics and present their findings as slides, a paper, or a poster:

- Causes of the Great Famine (for example, environmental, economic, and political circumstances that contributed to the famine)

- North Korean defectors (in China vs. in South Korea)

- North Korean borders, especially the Yalu River and DMZ

- Countries that provided aid to North Korea during the famine (including the U.S.)

- Education in North Korea

- Leaders of North Korea since 1948 and how each developed a narrative and cult of personality around themselves.

Four Corners

Young-bum said, “Morality is a great song a person sings when he or she has never been hungry. You can walk the noble road, Sungju. But if you die because of it, nobody will remember you were a noble person. Just a fool. Our enemy is death now.”

- Discuss this quote with a partner and share what you think it means. Do you agree or disagree?

- Join with another set of partners to form a small group; share your conclusions about the quote together.

- Teacher should label each corner of the room Strongly Agree/Agree/Disagree/Strongly Disagree. Then provide the first part of the sentence, “Morality is a great song a person sings when he or she has never been hungry,” and have students move to the corner they feel best describes their opinion. Ask students to defend their position. Other students can move if a peer’s argument is persuasive.

Timeline & Map

Have students develop a timeline and a map of events in Every Falling Star. Divide the class in two, half working on each aspect, then switch halfway through.

Possible Resources

- Chol-Kwan, Kang and Rigoulot, Pierre. Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag. Basic Books, 2005.

- Demick, Barbara. “Barbara Demick | Everday Lives in North Korea.” YouTube, June 9, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yUkW8ZiMHCs.

- Demick, Barbara. Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea. Random House, 2010.

- Stimson Center. 38 North https://www.stimson.org/project/38-north/

- Lee, Hyeonseo. “My Escape from North Korea” | TED Talk, February 2013. https://www.ted.com/talks/hyeonseo_lee_my_escape_from_north_korea.

- Lee, Sungju. “Every Falling Star by Sungju Lee.” YouTube, June 14, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4jaa2sTelk4.

- Lee, Sungju. “Sungju Lee Shares His Defector Story | 2018 Democracy Award.” YouTube, June 20, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zq__qjvaik.

- Richardson, Christopher. “North Korea’s Kim Dynasty: The Making of a Personality Cult.” The Guardian, February 16, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/16/north-korea-kim-jong-il-birthday.

- Seth, Michael J. “North Korea’s 1990s Famine in Historical Perspective.” Association for Asian Studies, August 18, 2020. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/north-koreas-1990s-famine-in-historical-perspective/.

- Youn, Soo. “Pictures of a Train Ride through North Korea.” Travel, May 3, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/take-train-through-north-korea-unseen-countryside.

Author: Michael-Ann Cerniglia, Upper School History Teacher, Winchester Thurston,

2023

[1] “38th Parallel.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/place/38th-parallel.

[2] Michael J. Seth, “North Korea’s 1990s Famine in Historical Perspective,” Association for Asian Studies, August 18, 2020. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/north-koreas-1990s-famine-in-historical-perspective/.

Every Falling Star video with the author Sungju Lee

North Korea in the World from East-West Center and National Committee on North Korea

Korea Society in New York City lesson plans

Archived Book Group Every Falling Star. (Once you have created a login for yourself at asiaforeducators.org, you are able to view and access all current and archived offerings from the main page. One (free) login suffices for all)

An Indies Introduce Selection of the American Booksellers Association

A Junior Library Guild Selection

2016 Parent’s Choice Award winner

2016 Cyblis Award Winner

2017 CBC Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People

2017 Notable Books for a Global Society

2018 Sakura Medal, nominee