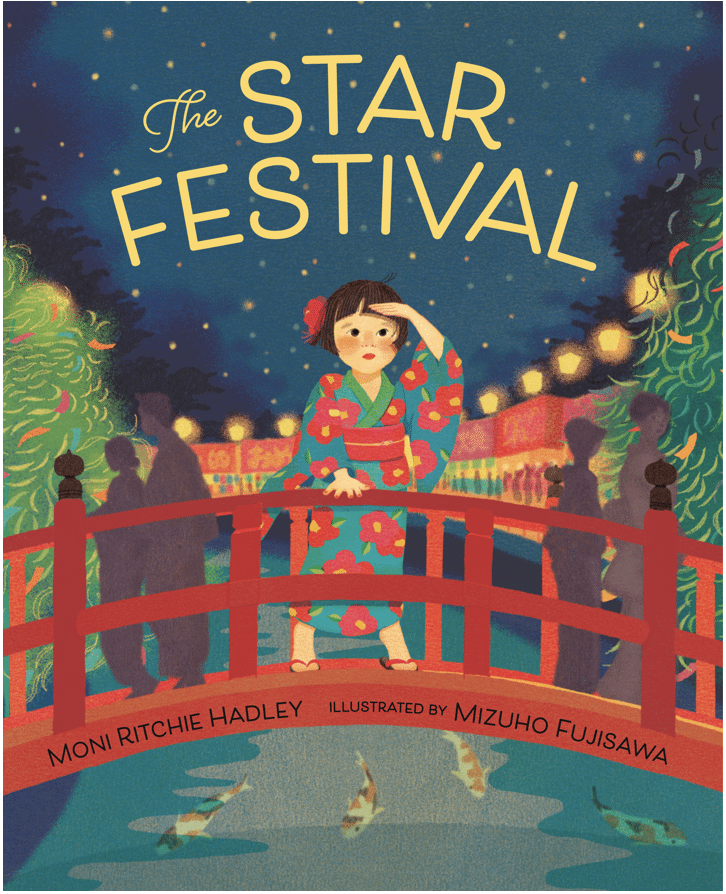

The Star Festival

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: family, multigenerational, folktales, holidays

Tanabata Matsuri, the Star Festival, celebrates a popular folktale: The Emperor of the Heavens separates his daughter, Orihime, from her love, Hikoboshi, all year—but on this day the two stars finally reunite, crossing a bridge over the Milky Way. For Keiko, her mama, and her grandmother, Tanabata is about making tanzaku wishes, taking in the colorful decorations, and eating delicious food like nagashi somen and shaved ice. But when Obaasan gets lost in the crowd, Keiko and Mama must make their own bridge to find her again—and see if their tanzaku comes true.

Introduction

In The Star Festival, written by Moni Ritchie Hadley, young Keiko (pronounced: KAY-koh) is enjoying an exciting evening with her mother and Oba (pronounced: oh-BAH) at the Tanabata Matsuri (pronounced: tah-NAH-BAH-TAH MAHT-SUE-ree), or Star Festival. On the hunt for shaved ice and other festival delights, Keiko and her mother become separated from Oba. Their subsequent quest to find Oba introduces readers to Japanese festival culture at every turn. Illustrator Mizuho Fujisawa’s rich artistry paints a vivid picture of Tanabata that is absorbing from start to finish, making The Star Festival a delightful dip into one of Japan’s most famous celebrations.

Historical Background

Tanabata Matsuri is a festival based on the Chinese folktale “The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl.” According to the most popular version of the tale, the Emperor of the Heavens had a daughter, Orihime (pronounced: oh-REE-he-may), who wove beautiful cloth on the banks of the Heavenly River. Orihime despaired as her work kept her from meeting anyone and falling in love. Taking pity on his daughter, the Emperor of the Heavens allowed her to meet Hikoboshi (pronounced: he-KOH-boh-she), a cowherd from the other side of the river. It was love at first sight. The lovers married, yet before long they began neglecting their duties to spend time together. As punishment, the Emperor of the Heavens once again separated them with the Heavenly River and forbade them from meeting. Orihime, longing to be with Hikoboshi, pleaded with her father to allow them to see each other. Moved by his daughter’s tears, the Emperor decided that they could meet on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month if their work was finished. The day finally came and their duties were complete, but the lovers found they could not cross the Heavenly River, for there was no bridge. Orihime wept so much that her tears summoned a flock of magpies. The magpies formed a bridge with their wings so she could cross the river and be with her beloved once more. It is said that the magpies return every year on Tanabata to create the bridge; if it rains, the magpies cannot come, so people pray for clear skies.

Tanabata became popular in Japan in the seventeenth century. The name “Star Festival” alludes to a folktale: Orihime and Hikoboshi are the stars Vega and Altair, and the Heavenly River is the Milky Way. The customs surrounding the celebration draw from other Japanese festivals that occur around the same time of year. Tanabata activities include eating, playing games, watching fireworks, and dancing.

Tanabata in Japanese Culture

In The Star Festival, readers are introduced to many aspects of traditional Japanese culture, including food and clothing. For example, Keiko and Oba are excited to eat shaved ice—a sweet treat for a hot summer festival—and long, cold noodles called nagashi sōmen (pronounced: nah-GAH-SHE SO-men). Other popular festival foods include yakisoba (fried noodles; pronounced: yah-KEY-SO-bah), takoyaki (fried dough balls containing octopus; pronounced: tah-KOH-YAH-key), okonomiyaki (grilled savory pancakes; pronounced: oh-KOH-NO-ME-YAH-key), and yakitori (charcoal-grilled chicken skewers; pronounced: yah-KEY-TOE-REE).

Like Keiko’s family, festivalgoers often wear traditional clothing. Summer kimono made of cotton, known as yukata (pronounced: you-KAH-TAH), are worn with a wide cloth belt, or obi (pronounced: OH-bee), tied around the waist; the ensemble is often completed with wooden sandals called geta (pronounced: geh-TAH). Keiko also gets up close and personal with taiko (pronounced: TIE-koh), large drums that are struck with thick sticks called bachi (pronounced: bah-CHEE), which lead the festival parade.

The Star Festival also introduces the reader to the signature element of Tanabata: the making of tanzaku(pronounced: tahn-ZAH-KU). Tanzaku are long, narrow strips of colorful paper on which people write wishes. The tanzaku are tied to bamboo, lining the streets with color. At the end of the festival, the tanzaku are burned or set afloat on a river; it is believed that this is when the wishes come true.

Author: Evelyn Seitz, researcher and translator

2023

The Best Children’s Books of the Year 2022, Bank Street College