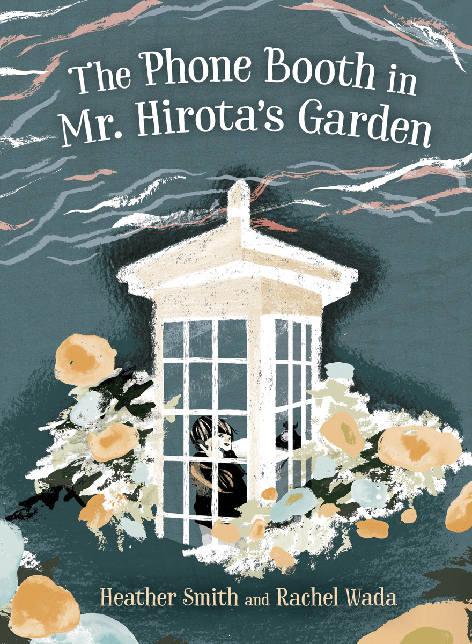

The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: tsunami, death, grief, family, resilience

When the tsunami destroyed Makio’s village, Makio lost his father . . . and his voice. The entire village is silenced by grief, and the young child’s anger at the ocean grows. Then one day his neighbor, Mr. Hirota, begins a mysterious project—building a phone booth in his garden. At first Makio is puzzled; the phone isn’t connected to anything. It just sits there, unable to ring. But as more and more villagers are drawn to the phone booth, its purpose becomes clear to Makio: the disconnected phone is connecting people to their lost loved ones. Makio calls to the sea to return what it has taken from him and ultimately finds his voice and solace in a phone that carries words on the wind.

The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden is inspired by the true story of the wind phone in Otsuchi, Japan, which was created by artist Itaru Sasaki. He built the phone booth so he could speak to his cousin who had passed, saying, “My thoughts couldn’t be relayed over a regular phone line, I wanted them to be carried on the wind.” The Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011 destroyed the town of Otsuchi, claiming 10 percent of the population. Residents of Otsuchi and pilgrims from other affected communities have been traveling to the wind phone since the tsunami.

Story Background: The story presented by Heather Smith in The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden is based on the true story of a phone booth installed by Itaru Sasaki (pronounced: ee-TA-rue | sa-SA-key). Mr. Sasaki placed the phone booth in the garden of his home in Ōtsuchi 大槌町 (pronounced: OH-sue-chi), Iwate Prefecture 岩手県 (pronounced: e-WAH-tay), located in the northeastern Tohoku 東北地方 (pronounced: TOE-HO-koo) region of Japan a year preceding the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. The phone booth, known colloquially as “The Phone of the Wind” or “Wind Telephone” (風の電話or Kaze no Denwa), drew many individuals looking to contact their lost loved ones taken so suddenly from them in the huge tsunami that followed the earthquake. The phone booth’s notoriety grew after Mr. Sasaki was interviewed by Japanese broadcaster NHK for a 2016 documentary. After that, a public radio producer from the program, This American Life, brought the story to an English-speaking audience later that same year in the episode “One Last Thing Before I Go.”

Authorship, Accuracy, and Authenticity: Heather Smith was inspired by “the sense of hope and resilience” found in the public radio story and embarked on fictionalizing it for a young audience. Smith, however, has altered the timing of particular events for the fictionalized narrative. Perhaps most notably is the motivation for creating the “Wind Phone.” Unlike Smith’s fictional character, Mr. Hirota (pronounced: he-ROW-ta), the reasoning behind the phone was not related to the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. Rather, it was from the grief over the death of Mr. Sasaki’s cousin in a motorcycle accident about a year before the disasters. Although the author is taking creative liberties with the phone’s origin, she does accurately capture the rest of the story of the “Wind Phone,” even though she is filtering her narrative through the This American Life and NHK stories that relayed the tale to a wider audience.

The Wind Telephone in Ōtsuchi, Japan. Image by Matthew Komatsu (https://longreads.com/2019/03/11/after-the-tsunami/)

The Wind Telephone in Ōtsuchi, Japan. Image by Matthew Komatsu (https://longreads.com/2019/03/11/after-the-tsunami/)

Cultural Understanding: According to Mr. Sasaki, the impetus for placing the phone booth was born out of his need to have a space for expressing the loss of his cousin as well as creating a meaningful link to him. In an interview with NHK, Mr. Sasaki suggests that “because my thoughts could not be conveyed over the regular phoneline, I wanted them to be carried on the wind.” The physical location of the “Wind Telephone” may account for its name as it sits on a particularly windy hillside overlooking Ōtsuchi and the sea. The phone booth itself is a wooden structure, painted white with glass panels, harkening back to an older style of public telephones seen in rural communities. While it can be problematic to generalize, Japanese people do not usually display strong emotions publicly. These emotions are often displayed only in private or with close relations. Thus, the relative privacy of a phone booth could offer a space to express one’s emotions. Lastly, remembrance and communication with departed family members long have held a place in Japanese culture. Particularly during the late summer Obon festival お盆 (pronounced: oh-BON), Japanese people return to their hometowns to reunite with family, both living and deceased. This includes visiting ancestral shrines or gravesites, welcoming the ancestors back to the home and then, after a period of time, escorting them back to the cemeteries. In the past, this veneration and remembrance was thought to pacify and assist the spirits of the dead in releasing their suffering. Thus, the continued recognition of and communication with the deceased still plays a role in Japanese life.

Historical Background: To better understand the book, it’s necessary to know the magnitude of the disaster that serves as the backdrop for the story. In Japan, the event is known as the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 and is often abbreviated 3.11 in the Japanese media. Outside of Japan this event is often referred to as Japan’s Triple Disaster. This name is in reference to three related events that occurred on March 11, 2011, including the initial earthquake, the tsunami and then the eventual nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. These events struck the eastern region of Japan known as the Tohoku region. The 9.0 megathrust earthquake was the fourth most powerful ever recorded and is responsible for shifting the entire Earth’s axis by several centimeters. While powerful, the earthquake was responsible for only moderate damage as nearly all buildings in Japan are required to meet strict building codes to prevent complete failure. However, the tsunami that followed, generated by the massive, sudden movement of the Earth’s crust, created a wall of water reaching many tens of meters into the air. In a matter of moments, the tsunami wave swept away everything in its path. Not long after, total power failures caused by flooding at the coastal Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station brought about a meltdown of the nuclear fuel rods at its Number 1, 2, and 3 reactors. The meltdown of the nuclear fuel caused an explosion of steam, which released radioactive particles into the air. These particles carried by the wind contaminated many surrounding communities and were even detected in Tokyo, Japan’s capital. As of 2021, the aftermath and cleanup from these three disasters is still ongoing. Many of the coastal communities are still in the process of rebuilding communities washed away by the waves and cleanup from the nuclear contamination continues.

The scale of damage inflicted by the disasters is estimated to be one of the costliest in history by the World Bank. The disasters were responsible for 19,729 people killed, 6,233 injured and 2,559 still missing. In the immediate aftermath, 470,000 people were evacuated from their homes into temporary housing; nearly ten years later some residents are still displaced. In the years since the initial disasters, the town of Ōtsuchi, location of the physical phone booth, still has 425 missing and unaccounted for residents, one of the highest numbers in the affected area.

Illustrations and Art: The illustrator of the book, Rachel Wada, described her art as utilizing, “traditional Japanese art forms and techniques such as sumi-e and calligraphy,” when creating the images seen in the book. Sumi-e 墨絵 (pronounced: sue-ME-eh) is the Japanese word for a form of ink painting that dates back centuries in East Asia. The painter uses black ink, like the kind used in calligraphy, in differing concentrations across paper or silk. This style of painting is heavily associated with Zen Buddhism as its simplicity, directness, and movement within the paintings work to inform what D.T. Suzuki characterized as “gives a form to what has no form.” Zen and sumi-e painting were linked in Japan from the very outset as many early sumi painters were Zen monks, not professional artists, utilizing painting and calligraphy as a teaching tool to often illiterate students. Sumi-e is also linked to calligraphy as it shares the same type of ink and brushstrokes. Often, sumi-epaintings skillfully combine sections of calligraphy with playful artistic works that would inform or describe the text.

Splashed-ink Landscape (破墨山水Haboku-sansui, 1495) by Sesshū Tōyō. Tokyo National Museum (https://emuseum.nich.go.jp/detail?langId=en&webView=&content_base_id=101224&content_part_id=0&content_pict_id=0)

Splashed-ink Landscape (破墨山水Haboku-sansui, 1495) by Sesshū Tōyō. Tokyo National Museum (https://emuseum.nich.go.jp/detail?langId=en&webView=&content_base_id=101224&content_part_id=0&content_pict_id=0)

Author: Stephen Wludarski, Program Assistant for the NCTA and Japan Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh. He is also former JET teacher in Kobe, Japan.

2021

Suggested Readings and Resources

Glass, Ira, Jonathan Goldstein and Miki Meek. “597: One Last Thing Before I Go.” Produced by WBEZ. This American Life. September 23, 2016. Podcast. https://www.thisamericanlife.org/597/one-last-thing-before-i-go-2016

“Japan Disaster Digital Archive.” Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University. https://jdarchive.org/en

“Landscapes of Autumn and Winter by Sesshū Tōyō” Tokyo National Museum. https://www.tnm.jp/modules/r_collection/index.php?controller=dtl&colid=A1398

“The Phone of the Wind: Whispers to Lost Families” Produced by NHK. NHK Specials. Season 1, Episode 3. March 11, 2017. https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6uepb9

The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden is a heartwarming tale about a young Japanese boy who uses the help of a kind neighbor to learn to cope with the loss of his father and his town after an earthquake and tsunami disaster. This book is suitable for any elementary grade level, although it would be most effective in second through fourth grade classrooms. Students in kindergarten and first grade could enjoy this story as a read-aloud, but would most likely not be able to have detailed discussions about the text. The book may be relatable to younger students if they have suffered a loss of some kind in their own lives, but otherwise teachers of younger students would have to gauge whether or not the theme of the book would be appropriate for their class. The book is recommended highly for second grade through fourth grade because, at these grade levels, students are able to pull apart texts and look at the deeper meaning behind the author’s words. Also, at these grade levels, the book could be independently read by students or could be shared as a read-aloud. Below are some suggestions of how this book could be used in second through fourth grade classrooms.

Inquiry Based Discussions:

One activity that could be used in second through fourth grade is having an inquiry-based discussion surrounding the book. For this activity, students would need their own copy of the book. During the first reading of the book, the teacher would read the book aloud to the students, and the task of the students would be to listen to the text. For the second read, the teacher would read a book aloud to the students again. This time, the students would be tasked with using sticky notes to mark words they do not understand in the text, parts of the text that interest them, and questions that they have about the text. Students can quickly mark parts of the text that interest them with an exclamation point drawn on a sticky note, and they can mark the questions by writing a question mark on a sticky note. At the end of the second reading, the teacher should record all of the students’ questions. At this stage, the teacher does not discuss the questions unless there are questions that signify a misunderstanding about the text. Students then write and/or draw about one question they have about the text. Before the third and independent reading, address any vocabulary-based questions or questions that have one correct answer from the text. Then encourage students to read the story independently or with a partner. Have students record something different they notice when reading the text on their own or with a partner.

The final component of inquiry-based discussion is having the discussion itself. Before having the discussion, the teacher should develop questions that will require students to think critically about the text. The questions should be able to be supported with evidence from the text. For each discussion, only one to three questions need to be chosen. Some example questions for this text are: why did the author say that a big watery hand took Makio’s (pronounced: ma-KEY-o) voice away, how did the ocean impact the story, and how did the phone booth impact the story? With older students, it is possible to use some of the questions they developed for the discussion. Share one of the questions with the students ahead of time. Allow them a few minutes to write down their answers and to cite evidence from the text. In younger grades, this may simply look like recording the author’s words and writing down an estimated page number.

When students are finished with answering the question on paper, have them gather in a circle. The teacher’s role in the discussion is to only ask questions. The students can take turns sharing their answers with the group, ensuring that they quote evidence from the text. Students should be taught how to politely agree and disagree with each other’s thoughts. Inquiry based discussions should typically last for twenty to thirty minutes. If the class is large, students can be broken up into two groups.

Common Core Standards that fit this activity include:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.1

Ask and answer such questions as who, what, where, when, why, and how to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.2

Recount stories, including fables and folktales from diverse cultures, and determine their central message, lesson, or moral.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.1

Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.2

Recount stories, including fables, folktales, and myths from diverse cultures; determine the central message, lesson, or moral and explain how it is conveyed through key details in the text.

Comprehension Strategies:

There are many comprehension strategies that can be taught using The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden. One of the skills this text can be used for is making inferences. Learning how to make inferences can often be a challenge for students of any age, but this text provides many opportunities to allow students to practice this skill. One part of the book teachers could discuss is when the author writes about the ocean saying O-hi-o but then one day it roared. Teachers can ask students to draw conclusions about why the author chose to include this section in the text. They can help students make connections between O-hi-o, the sound the waves are making, and the shortened version of the Japanese greeting for saying good morning, ohayō おはよう (pronounced: oh-HI-yo).

Another section of the book to look at is when the author writes “[a]n old fashion phone sat on the table. It had no plugs or wires. It was a phone connected to nowhere.” The students can draw conclusions about why Mr. Hirota would choose to use a phone booth and why the phone was connected to nowhere. The students can also make inferences about how and why the phone booth was able to help Makio. Note: the word ohayōin Japanese is a shortened version of “good morning” and is pronounced almost exactly like the name of the U.S. state Ohio. The full morning greeting is ohayō gozaimasu おはようございます (pronounced: oh-HI-YO | GO-ZA-EH-MAH-su)

Common Core Standard that fit this activity include:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.4.1

Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

Discussing the author’s craft is another powerful skill that can be taught easily by using this text. The author uses a lot of interesting techniques that would be both easy and engaging to discuss with students. The most noticeable style of this author is using different fonts for different sections of the book. Students can discuss why the author chose to write the words “It roared” in bold and slightly bigger texts, then wrote the words “rumble, boom, [and] crash” in all caps and much larger text. Invite students to find other parts of the text where the font size or style changes. Students can discuss as a whole group, in a small group, or with partners about why the author may have chosen these font changes.

This story would also be effective for discussing the author’s purpose. While the students could draw general conclusions about the author’s purpose for writing based on the words in the text, there are also author notes in the back of the book that would help students discover the author’s purpose for writing in more depth. The notes describe the real-life story of Itaru Sasaki (pronounced: ee-TA-rue | sa-SA-key) and how he built a phone booth in his garden to deal with the loss of a cousin. Then, when the 3/11 tsunami hit, more and more people came to use the phone booth (see the Culture Notes document for more). Students could research more about Itaru Sasaki by looking at the many websites that have recorded his story online.

Vocabulary is another strategy that this text could be used to explore. This text uses a variety of colorful language for students to examine. Some examples of these words are “snatched,” “village,” “crept,” “lapped,” and “phone booth.” Students could use the vocabulary in this text to complete Frayer Models, design word clouds, complete word sorts, and create word webs.

A Common Core Standard that fits this activity is:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, distinguishing literal from nonliteral language.

Writing Activities:

There are several different writing options that could accompany the reading of this text. This book would be a great mentor text for helping students to develop their own writing styles. Similar to discussing craft, students could examine how different font sizes and styles effect the meaning of the text and the way that it is read by a reader. Students can then experiment with changing their own text sizes and styles to help emphasize their own writing in a narrative piece.

Common Core Standards that fit this activity include:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.2.3

Write narratives in which they recount a well-elaborated event or short sequence of events, include details to describe actions, thoughts, and feelings, use temporal words to signal event order, and provide a sense of closure.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.3

Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

Another idea for a writing piece would be comparing this text with another text or comparing the ocean in the story with the character Makio. Although the ocean is not exactly a character in the story, it is viewed by Makio as if it almost has a personality. Students could compare the ocean seeming angry with Makio’s feelings of anger. Students could also compare themselves with Makio as another option, since making connections with characters in a story helps students to relate to a text in more depth. One more short writing piece students could work on is writing a script for another conversation Makio or another villager might have with the phone both.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.6

Acknowledge differences in the points of view of characters, including by speaking in a different voice for each character when reading dialogue aloud.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.9

Compare and contrast the themes, settings, and plots of stories written by the same author about the same or similar characters (e.g., in books from a series)

This book could be connected to a science unit on weather. Students could conduct research on tsunamis and how they impact different areas. This could lead to writing a research report or creating a lapbook or trifold display. For a social studies writing piece, students could research the history of the phone booth and write about how it was used and why we no longer use these in the U.S. and Japan. This text could also be a component to a larger unit about Japan. Teachers can use other videos, texts, and online sources to have students learn more about Japan. Students can learn how to write haiku poetry and use The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden as inspiration to write their own haiku about the book.

Common Core Standards that fit this activity include:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.2.2

Write informative/explanatory texts in which they introduce a topic, use facts and definitions to develop points, and provide a concluding statement or section.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.2.7

Participate in shared research and writing projects (e.g., read a number of books on a single topic to produce a report; record science observations).

Author: Kimberly Adams, Hillel Academy of Pittsburgh

2020

School Library Journal Best Books 2019

2020 USBBY Outstanding International Book

2020 Elizabeth Mrazik-Cleaver Canadian Picture Book Award