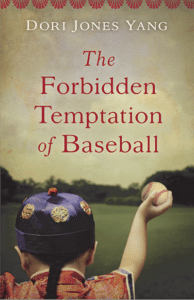

The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball

- Fiction

- Set in China and the U.S.

Keywords: sports, immigration, customs, perseverance

The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball is a lively, poignant, and nuanced novel based on a little-known episode from history, when 120 boys were sent to New England by the Emperor of China in the 1870s, long Manchu mandated braids down their backs, to study. Woo Ka-Leong (Leon) and his brother, Woo Ka-Sun (Carson) reside with the Swann family in Suffield, CT. Through Leon’s expectations and his confrontations with alien customs, the reader learns about both pre-modern Chinese and Victorian-era American societies and technologies. The novel features several appendices, including a short bibliography, questions for discussion, and trivia for readers who will want to learn more. The boys’ experiences are both timely and timeless.

The book gives American readers a glimpse into what it feels like to be a foreigner in the United States and will spark thoughtful discussion.

The Story

Two brothers, Woo Ka-Leong and Ka-Sun, the second and third sons in their family, travel to New England as part of the Chinese Educational Mission in 1875. The goal of the mission is to learn English, attend high school, and go to university, all while keeping up with their Chinese and resisting becoming “Americanized.” The boys are placed with the Swann family in Suffield, Connecticut. Carson (his American name) struggles to learn English and adjust to life in America. Leon (his American name) learns how to play baseball and gets excited about trains.

Their lives begin to take different paths as each struggles to fulfill the ideals of Confucianism. Leon struggles to follow his elder brother’s guidance. And Carson struggles to keep studying so that he can pass the Civil Service Exam on his return to China, the exam that his elder brother is studying for back home. Passing this exam is required to secure a government position.

The boys cope with these challenges in different ways, leading to a crisis at the 1876 World’s Fair, where Leon’s essay on trains is selected to be showcased over Carson’s. In the end, Carson returns to China while Leon stays in Connecticut, joining the baseball team and attending high school. Although the boys and location are fictional, the Chinese Educational Mission is historical fact. It was a mission organized by Qing-dynasty officials that sent 120 Chinese boys to be educated in the U.S. from 1872 to 1881.

A Short History of the Qing Dynasty

When the Manchus overthrew the Ming dynasty in 1644, they were the second non-Han group to control China—the first being the Mongols, who established the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). The Manchus ruled China as the Qing dynasty until the revolution of 1911. During this time, boys and men were required to show their loyalty to the emperor by shaving the front of their head and letting their hair grow long in back, braiding it to form a “queue.” Cutting off the queue was strictly forbidden.

By the time the boys in this story were crossing the Pacific Ocean to study in the U.S., China was emerging from a long period of turmoil. Its structured trade system had been dismantled by the British, who defeated China in the Opium Wars (1839–60). The economy was then ravaged by unemployment and unrest in society. China was brought to its knees with the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864).

By the end of the 1860s many impoverished Chinese men had immigrated to the U.S. to seek their fortunes in the Gold Rush. What they found instead was backbreaking work on the western section of the transcontinental railroad and discrimination almost everywhere they looked. The Chinese government was determined to rebuild and compete on the world stage with the Western powers. The Self-Strengthening Movement of 1861–1895 began with the idea that China could modernize through institutional reforms and the introduction of Western technology. It was during this time that two reformers came up with the idea for the Chinese Educational Mission.

A Spark of Inspiration

Yung Wing had little success finding work in China. He had attended missionary schools, and didn’t have enough Confucian education to take the civil service exam. So, with limited job opportunities in China, he went to the U.S. to attend Yale University, becoming the first Chinese graduate. After graduation, he returned to China to help with efforts to modernize the country. In 1872, he met with Zeng Guofan of the Self-Strengthening Movement, and the idea for the Chinese Educational Mission was born.

The idea was new: send cohorts of boys to the U.S. to gain an education in modern technology. Then they would return to China to help modernize the country. Yung Wing himself would travel with the boys and serve as a mentor in Hartford. Wing was comfortable in American society. His friends from Yale remembered him with fondness, and he seemed to make a good impression on everyone he met, eventually marrying an American woman.

The Chinese Educational Mission

The purpose of the Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) was to select 120 boys aged twelve to sixteen to go to the U.S. to study for fifteen years. Because of the position of first-born sons in the Confucian tradition, only second or third sons could apply, and many of them did. Most boys came from southern merchant families, with the goal of learning English to help with the business. In return for being away from China for fifteen years, the boys would receive an education, a stipend, and on their return, would be promoted to guansheng, equivalent to passing the lowest level of the civil service exam. They were then honored and allowed to wear scholar robes.

The Journey to New England

The boys first spent time in Shanghai, learning English and continuing their Chinese studies before leaving for the U.S. The first cohort left in August 1872. From Shanghai they made their way via Japan to San Francisco in first class on a steamship. Awaiting them in San Francisco were new sights, but they were far from the end of their journey. To cross the country, the boys boarded the transcontinental train, which transported them to what would be their home for the next decade. As described in this book, one of the trains that had the boys on it did indeed get robbed by Jesse James’s gang. The group’s train journey ended in Springfield, Massachusetts, where the boys either met with their host families or went to Harford, Connecticut, where the CEM headquarters was located.

Host Families

Great care went into selecting host families. The process was competitive, with 122 families volunteering and promising not to Christianize the boys. In the end only 35 families hosted the original 85 boys. Rural locations in Connecticut and western Massachusetts were preferred so that the students wouldn’t be as easily tempted by American ways as they could be in the city. The selected families were also close to train lines in order to get to Hartford easily. The boys’ first task in the U.S. was to gain a level of fluency in English. Once it had been deemed that they were ready, they would then attend high school and later college in the Northeast, where the CEM leaders had multiple connections.

CEM Headquarters

To avoid assimilation, the boys would spend time at the CEM headquarters, which was located on Collins Street in Hartford. It was big and spacious, with enough room for the boys’ summer lodging and Chinese studies. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) lived near the headquarters. He and Yung Wing became friends, and Twain supported the boys as much as he could, including lobbying President Grant to continue the mission when it was terminated by Chinese officials.

Assimilation in the U.S.

Many boys got their photo taken when they first arrived in the U.S. These first pictures show young men and boys with shaved foreheads and queues that hung down their back as an outward sign of their loyalty. But as their time in the U.S. went on, and despite the best effort of the CEM, the boys started to assimilate into U.S. culture. Their clothes began to resemble the clothes worn by the boys they went to high school and college with. Their hairstyles, at least in the front, looked American, but they still had a queue in back, even if it was placed inside their shirt collar.

The Popularity of Baseball

Another way that students adapted to life in the U.S. was to immerse themselves in the sports that were popular at the time, including football, rowing, shooting, and baseball. In many cases they joined sports teams at their schools. Among the Chinese boys, the popularity of baseball could not be denied. Many boys played on their high school, town, or college teams. They even formed their own baseball team in 1878: The Orientals, also known as the Celestials. In the 1880s the team joined the world of semi-professional baseball.

The Celestials left their mark on baseball and was one of the last things that the boys did before returning to China. When the program ended in 1881, the boys made the return journey. They had time in Oakland before they boarded the ship home, so the Celestials played an exhibition game against the Oakland team. By many accounts the Oakland team was favored to win, but the Celestials won.

1876 World’s Fair

The 1876 Centennial International Exhibition, the first official world’s fair in the United States, was held a hundred years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence and ten years after the upheaval of the Civil War. Crowds descended on Philadelphia to see the displays from countries around the world. The Chinese exhibit featured porcelain, tea, jade, and hand-sculpted ivory. The Chinese themselves drew people, who were fascinated by the workers in their traditional clothes setting up the exhibit. Then people flocked to the exhibit to see the life-sized dolls in traditional clothing and to get the autograph of someone from China.

When the CEM boys went to the fair in August to learn about the machinery, fairgoers gawked at them. The boys met President Grant while they were there, and some of them entered the essay contest. The big draw of the fair was the Corliss Centennial Steam Engine. In the book, this was the engine that Leon fell in love with and wrote about, in an essay that won the contest.

The End of the Chinese Educational Mission

The book ends with the CEM program running strong. But in December of 1880 the Chinese emperor issued an edict criticizing it. In response, the government recalled the boys of the Chinese Educational Mission for various reasons due to costs, racist policies culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the concern that they were becoming too Americanized. The biggest reason though, was the loss of favored nation status to Japan, meaning that the boys could not attend West Point as many wanted to.

Despite interventions from Mark Twain and President Ulysses S. Grant, the program officially shut down June 8, 1881. The boys were expected to return home, starting their journey back in September of 1881. When they finally returned home after almost ten years, they encountered a chilly reception, and a nation that had not really changed much in their absence.

Back in China

The CEM students had hoped for a triumphant return to China, but the political tide had turned against the West. They had lived in the U.S. for such a long time that they were treated with some distrust and had difficulty finding work. They didn’t have the traditional Confucian education, and their language skills had suffered in their fifteen-year absence from China. They were sent around the countryside to work at various jobs, including at the Fuzhou Navy Yard, where four of them died in a bombing during the Sino-French War of 1884. Eventually they were accepted into Chinese life. Many received government rankings, and some did indeed help build the railroad in China. One of them attended the coronation of King George V as an official delegate from China.

Most of the boys kept in touch with their host families in the U.S. The Connecticut Historical Society has many letters that were written back and forth. The bond was so strong that some former students sent their own children to study in the U.S. and stay with their former host families. Over the years, New England newspaper articles reported on the CEM reunions in China and updates on the former CEM students’ lives. Around 1937 an American newspaper reported on a reunion in China held by the twenty men who were still living; their average age at the time was seventy-six.

Further Reading

Rhoads, Edward J.M. Stepping Forth into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872–81. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

This accessible book is the definitive source for information on the CEM. It goes into depth about all aspects of the mission and includes maps of China and the U.S. It also includes detailed information about the boys, their host families, the schools they went to, and their lives in China after their return.

From the Connecticut Historical Society: “Yung Wing, the Chinese Educational Mission, and Transnational Connecticut.” https://connecticuthistory.org/yung-wing-the-chinese-educational-mission-and-transnational-connecticut/

“Chinese Who studied in Hartford for Many Years Send Greetings to Their Many American Friends,” Hartford Daily Times, 6 August 1936. https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collection/5983/id/961/rec/13.

A chapter from a book about the 1876 World’s Fair focusing on China:

http://www.gutenberg-e.org/haj01/print/haj10.pdf

A great article describing what was brought to the World’s Fair and what was sold:

Pitman, Jennifer. “China’s Presence at the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876.” Studies in the Decorative Arts 10: 1 (2002–2003), 35–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40662992. Accessed 2 May 2024.

Thomas La Fargue Collection: https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collection/5983

The Thomas La Fargue Collection from Washington State University has a trove of primary and secondary sources on the CEM, especially covering after they returned to China.

“Chinese Who studied in Hartford for Many Years Send Greetings to Their Many American Friends,” Hartford Daily Times, 6 August 1936. https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collection/5983/id/961/rec/13.

“Septuagenarians Reunion,” [Unknown Newspaper], circa 1937. https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collection/5983/id/955/rec/63.

Author: Rachel Knowles

2024

I am neither athletically inclined nor particularly fond of baseball, but I do love reading about the experiences of others, and I am always interested in finding new ways to engage my students. The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball by Dori Jones Yang is a gem, based on an actual initiative in which China sent 120 boys to study in New England in the 1870s. The story focuses on Woo Ka-Leong (Leon) and his older brother Woo Ka-Sun (Carson) and their first year with the Swann family of Suffield, Connecticut. This book does an excellent job illustrating the challenges of living in a different culture and using a different language.

My district is among the most diverse in Pennsylvania, with many students who are first-generation Americans. The questions that Leong ponders undoubtedly resonate with students and provide multiple opportunities for conversation: Why is this done this way? What is this that we are eating? How do I behave in this setting? For an adult reading this text, it seems impossible to expect that the Chinese boys can both live and learn in a new culture and language while simultaneously remaining “gentleman scholars” and not becoming “too American.” Yet throughout the text, that is what we see the brothers attempt; one has great success while the other ultimately fails.

This book’s short chapters will engage students in grades 7 to 10, whether reading independently or as a group, making this text an ideal book to integrate into class in small segments. This would be especially useful for teachers in either history or literature arts classes that use block scheduling; reading and short writing or discussion activities can be done to supplement classwork. Set in the nineteenth century, the book also examines American culture at this time, offering further opportunities for students to consider how life has changed over the 150 years. What would life be like for the characters Julia and Charlotte now? How would Charlotte’s physical limitations be perceived or addressed in terms of improving her mobility and independence? What rights would these women, Mrs. Swann included, have now that they did not then? It becomes quickly apparent that this text would ideally be supported by historical context provided through either discussion or short supplemental readings.

Having students research the dress and beauty ideals of the period, both in the United States and China, is also valuable. My students in a grade 10 art class were immediately intrigued when I showed examples of how these characters would be dressed. When they saw how young women their age dressed in the 1870s, they asked “How did these ladies move or, you know, walk around in that?” Much like the children in the book, my students had questions about the hairstyles of both Leong and Elder Brother. This led to a very interesting conversation about traditional dress in a variety of cultures, and these inquiries could set the stage for a meaningful project researching the traditions and dress of their own ancestors.

Within moments of arriving at the Swanns’ home, the boys’ names are anglicized. This is not done out of disrespect or to force assimilation, but rather, it is how their names sound to English speakers. Although Leong is pleased, he is also concerned, knowing that this was forbidden by his teacher in China and realizing that Elder Brother is also displeased. Here, too, my students openly discussed their experiences with well-meaning teachers who suggested nicknames instead of learning how to say their names correctly. We talked about how that felt, for both the student and the teacher. This also provided an opportunity to reflect and discuss the idea of how it looks and feels when an authority figure is mistaken. At multiple instances throughout the story, Leong must make important decisions regarding when to follow the directives of his elder brother, the Chinese teachers, and the American family with whom he is living, and when to make his own decisions.

Dori Jones Yang offers an insightful portrait of an American family in New England. It is important to note that Mr. Swann is a minister, and the church is a significant part of Swann family life. Since this is an important part of story, teachers working with this text will need to discuss the historical role of religion in both the United States and China. Yang does an excellent job describing the many questions and dilemmas these new experiences raise for Leong.

Although baseball is a vital part of the text, this book is less about the game and more about the opportunities it provides for Leong to make friends, feel comfortable speaking English, and become a valued part of the Swann family. Baseball is also the catalyst for Leong’s growing sense of independence as he navigates the expectations of his brother, the Chinese Educational Mission, and his American family. I would recommend this text to all educators in the humanities, even those with little interest in baseball.

This text would also be ideal for use in two areas of tremendous growth in education—English as a Second Language (ESL), and classes focused on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). In addition to offering unique ways to learn about the culture and history of China and the United States during this time, the book is very emotional. Not long after the boys arrive in Suffield, they learn from a letter from China that their eldest brother is ill, and he subsequently dies. The ball, glove, and bat that Leong finds in the closet of the room he shares with Elder Brother once belonged to the Swann family’s only son, who died in an accident that also injured Charlotte, the daughter who now uses a wheelchair. And the death of Johnny’s mother helps Leong to see that his initial ideas about people and situations are not always correct. Ultimately, Leong’s thoughtfulness and willingness to re-evaluate situations are the key to his success; the inability of Elder Brother to do the same is his downfall.

Elder Brother is a complex character, and it can be challenging to feel sympathy for him, especially because of the way he physically abuses his brother. Although corporal punishment was not unusual at this time in either the American or the Chinese educational systems, the beatings that Leong endures are far too frequent and intense to be characterized as a method to correct behavior. It is unclear whether the head injury Elder Brother sustains in the opening chapter of the text is to blame for the way he takes his anger out on his brother; Leong ultimately forgives Elder Brother’s behavior, even as he is perplexed by it. Educators working with this text should be aware that this subject could be upsetting for some students, and they should be prepared to address questions and feelings that arise from reading about cruelty. Because of this, I would not suggest that this book be read by students younger than twelve.

Ultimately, there is much to appreciate and enjoy in this text. It is educational without being dull, and it touches on a wide variety of topics including, but not limited to, baseball. Yang’s writing style is engaging, and her story is based on historical events and real inventions. A tremendous number of historical and cultural connections can be made to enrich students’ understanding of the novel and the world that Leong experiences.

Author: Kachina Leigh, studio art and AP art history teacher

2024

Interview with author, Dori Jones Yang

Archived Book Group The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball. (Once you have created a login for yourself at asiaforeducators.org, you are able to view and access all current and archived offerings from the main page. One (free) login suffices for all)

2017 Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards: Gold Award, Pre-Teen Fiction – Historical/Cultural

2017 USA Best Book Award Winner in Children’s Fiction