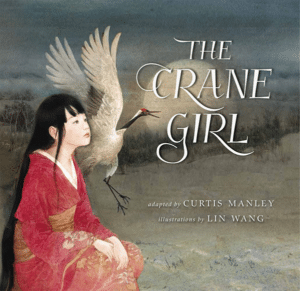

The Crane Girl

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: folklore, animals, trust, compassion

While gathering firewood, Yasuhiro comes upon an injured crane hidden in the snow. He rescues and comforts the bird, then watches as it flies away over the wintry hills.

The next night, a mysterious young girl arrives at Yasuhiro’s home seeking shelter from the cold. The boy and his father welcome the girl, named Hiroko, to stay with them. But when Hiroko notices that Yasuhiro’s father is struggling to earn money, she offers to weave silk for him to sell. After the fabric fetches a good price, the boy’s father becomes impatient for more silk, and his greed has a life-changing effect on them all.

Lyrical storytelling deftly interwoven with original haiku create a magical adaptation of a popular Japanese folktale—an inspirational story of friendship and the power of kindness to transform lives.

Story Background

The Crane Girl is based on the well-known Japanese folktale known as Tsuru no On’gaeshi (Crane’s Return of a Favor) or Tsuru Nyōbō (Crane Wife). This tale exists in many versions across Japan. The most famous version revolves around a young man who rescues a wounded crane caught in a trap. That very night, a young girl shows up at his home seeking shelter. Assisting the young man with chores, the girl spends her nights secluded in a room, urging him not to peek inside. Throughout the night, she weaves silk for the man to sell it at the market. One fateful day, consumed by curiosity, the young man breaks his promise and peeks into her room. To his surprise, he discovers the crane he had saved weaving its feathers into the silk. Unbeknownst to him, the crane had sought to repay his kindness, sacrificing itself to make the silk. Incensed by the breach of trust and the revelation of her true identity, the crane leaves.

This book closely follows the traditional storyline described above, and the synopsis is as follows:

Yasuhiro (pronounced: yah-SUE-HE-row), a young man collecting firewood, discovers a wounded crane trapped in the snow. Filled with compassion, he rescues and comforts the fragile bird before witnessing its graceful flight over the snowy hills. The following night brings a mysterious visitor to Yasuhiro’s home—Hiroko (pronounced: HE-row-co), a young girl seeking shelter and relief from the cold and hunger. Welcomed by Yasuhiro and his father, Ryota (pronounced: ROW-tah), Hiroko expresses her gratitude by offering to weave silk for them. The successful sale of this silk brings prosperity, but when Ryota’s greed takes over, the insatiable desire for more silk leads to significant consequences that change their lives. Through its skillful narrative, lyrical prose, and

complemented by original haiku, this book reimagines a classic Japanese folktale. The story becomes a testament to the transformative power of friendship, kindness, and a love that transcends humanity.

Before Reading

Some vocabulary to explore (look up in dictionaries or encyclopedias): buckwheat, stubble, crane, invisible, trap, unharmed, shudder, stroke, feather, fingertip, gently, firewood, shivering, bowing, chores, hearth, cat’s cradle (ayatori), unloading boats, baskets, noodles, kimono, loom, thread, fabric, scarf, market, bean sprouts, bolt of cloth, speckled, gold, village, merchants, tofu, ginger, weightless, trembling, docks, boast, chopsticks, rhythm, stare, flecked, wing, slammed, stumbled, bear, burden, gazing, pluck, threaded, sobbing, speck, dawn, flap, wingbeats, soar, marsh, clacked, beaks, chicks

Some questions to ask:

- What do you know about Japan?

- What kinds of animals are native to Japan?

- Do you know anything about cranes?

- What is a folktale?

- Do you know any folktales dealing with animals?

- Do you know any folktales about an animal that transforms into a human (or vice versa—a human that changes into an animal)?

- Do you know any folktales dealing with someone being kind to an animal?

- Do you know any stories involving someone trying to repay kindness shown to them by sacrificing their life?

- How can you show kindness to someone? Or to an animal? Or to nature as a whole?

- What does it mean to be greedy? What kinds of consequences come with being greedy? Was there a time when you acted greedily? If so, what happened afterwards?

- What comes to your mind when you hear the title “The Crane Girl”? What do you think happens in this story?

During Reading

Things to consider while reading:

- The relationships between Hiroko and Yasuhiro, Hiroko and Ryota, and Yasuhiro and Ryota

- Why Hiroko felt obligated to Yasuhiro and Ryota

- How acts of kindness and mercy can change lives

- The consequences of exploiting someone’s kindness

- The consequences of breaking promises

- The different effects of haiku-style poems (color-coded to represent each character’s thoughts) and prose storytelling

- How folktales reflect their culture and history

Try answering these questions as you read:

- What was Yasuhiro doing outside? (p. 1-2)

- What did Yasuhiro discover in the snow? (p. 1-2)

- Why did Yasuhiro hesitate before stepping onto it? (p. 1-2)

- What caused the crane to look “invisible”? (p. 1-2)

- Why was the crane there? (p. 1-2)

- How did Yasuhiro approach the crane? (p. 1-2)

- What actions did Yasuhiro take to assist the crane? (p. 1-2)

- What did Yasuhiro do to establish a connection with the crane? (p. 1-2)

- How did the crane express gratitude toward Yasuhiro? (p. 3-4)

- Who arrived at Yasuhiro’s door the following night? (p. 5-6)

- How would you describe the girl’s appearance? (p. 5-6)

- What was her purpose in seeking refuge? (p. 5-6)

- What decision did Ryota make regarding the girl? (p. 7-8)

- What did Ryota want the girl to agree to? (p. 7-8)

- What is the girl’s name? (p. 7-8)

- What was the name of the game Yasuhiro was teaching? (p. 9-10)

- Why did Ryota head into town every morning? (p. 11-12)

- What did Ryota bring back home each evening? (p. 11-12)

- What had happened to Yasuhiro’s mother? (p. 11-12)

- At what skill was Yasuhiro’s mother particularly adept? (p. 11-12)

- Who crafted Yasuhiro’s scarf? (p. 11-12)

- What did Hiroko attempt to offer? (p. 13-14)

- What request did Hiroko make of Ryota and Yasuhiro while she was weaving? (p. 13-14)

- How much time did it take her to weave the first bolt of cloth? (p. 15-16)

- How lightweight was that particular cloth? (p. 15-16)

- Who purchased the silk cloth? (p. 17-18)

- What did Ryota acquire in exchange? (p. 17-18)

- What prompted a change in Ryota’s behavior after he sold the cloth? (p. 17-18)

- How long did it take for the gold to run out? (p. 17-18)

- What action did Hiroko take when Ryota ran out of the gold from the sale of the first bolt of cloth? (p. 19-20)

- How much time did she require for weaving this time? (p. 19-20)

- Following the sale of the second bolt of cloth, what course of action did Ryota pursue? (p. 19-20)

- How long did it take for the gold to run out this time? (p. 21-22)

- What demand did Ryota impose on Hiroko? (p. 21-22)

- What was Hiroko’s response afterwards? (p. 21-22)

- What action did Yasuhiro take after Hiroko entered the weaving room? (p. 21-22)

- How much time elapsed after Hiroko entered the weaving room this time? (p. 23-24)

- Why did it take so long to weave this time? (p. 23-24)

- During this period, what was Ryota doing just outside the weaving room? (p. 23-24)

- What was Ryota concerned about during this time? (p. 23-24)

- Who opened the sliding door when the sound of the loom stopped? (p. 23-24)

- What did Ryota witness inside the room? (p. 23-24)

- What action did Yasuhiro attempt this time? (p. 23-24)

- Who slammed the door? (p. 23-24)

- Where did Ryota go after observing the situation in the room? (p. 24-25)

- How did Hiroko appear on coming out of the room? (p. 24-25)

- What did she carry in her hands? (p. 24-25)

- What were Yasuhiro’s first words to Hiroko when she came out of the room? (p. 26-27)

- What occupied Hiroko’s thoughts as she pressed her head against him? (p. 26-27)

- What motivated her to pluck her feathers for the cloth? (p. 26-27)

- What transformation occurred after she stepped outside the house? (p. 28-29)

- What action did Yasuhiro take after Hiroko in her crane form took off? (p. 28-29)

- What request did Yasuhiro make to Hiroko as he awoke from sleep? (p. 30-31)

- How did Yasuhiro get his wings? (p. 30-31)

- Where did Hiroko and Yasuhiro go afterwards? (p. 32-33)

- How did her people react to Yasuhiro? (p. 32-33)

- How did Hiroko and Yasuhiro live as cranes thereafter? (p. 32-33)

After Reading

Some questions to consider:

1. Character description

- Hiroko / Crane: Is she portrayed as a lonely, weak, and vulnerable girl? Or does she display resilience, kindness, and perseverance, and have a dedicated, hardworking nature?

- Yasuhiro: Is he depicted as a savior, showing mercy, kindness, and gentleness (such as stroking her feathers)? Does he demonstrate care for his family, animals, and a longing for his mother (such as holding his mother’s scarf to his cheeks)? Does he appear to have an honest nature?

- Ryota: Does he expect others to work hard for his benefit while being lazy himself (acting hypocritically)? Is he portrayed as demanding, driven by greed, blinded by wealth, caring only for his status in the society, and sometimes resorting to bullying tactics? In certain situations, does he exhibit fearfulness (when he falls back onto the floor) or cowardice (when he runs outside, into the darkness)?

2. Crane-ness in human form

- Appearance: Are there any indications of her crane origin in Hiroko’s human form? Do elements like the redness of a crane’s head or darkness of her tail correspond to certain features of Hiroko’s appearance or clothing, such as her eyes and long hair or the color of her kimono and obi sash?

- Behavioral resemblances: Are there parallels between Hiroko’s actions and those of a crane? For instance, her gestures, such as standing up and pressing her head against Yasuhiro, or bowing to Ryota and Yasuhiro?

- Symbolism in woven kimono silk: Do the design or patterns in her woven kimono silk hint at her crane origins? Are there depictions resembling the crane’s footstep on a bolt of cloth (symbolizing her arrival?) and a design depicting a crane flying over the ocean (symbolizing her departure?)

3. Reaction to the breaking of the promise

- When Ryota opens the sliding door and encounters the crane by the loom, he promptly runs off while the crane resumes weaving, transforming back into Hiroko. How do you interpret this reaction? Would you expect someone to immediately depart if a promise is broken? Or would you expect someone to finish the task, then leave? What motivated Hiroko to stay and complete her task despite the broken promise?

4. Symbolism in transformation

- When Hiroko transforms from human form into a crane and departs, the scene portrays an almost angelic figure. What do you think of this image? Do you perceive this portrayal as the author or artist hinting at Hiroko being a messenger from heaven? How do you interpret this transformation scene?

5. Endings in folktales

- Japanese folktales often conclude on a bittersweet or melancholic note, evoking poignant emotions. For example, most of the original crane folktales end with the sudden departure of the crane after the promise was broken. Japanese theatrical productions and films embrace sad endings that are believed to evoke deep emotional responses in audiences. In this retelling of the traditional folktale, the story takes a turn toward a happier ending as both Yasuhiro and Crane Hiroko thrive together. Compare the Japanese sad ending and the American happy ending—which resonates more with you? Why do you think one type of ending appeals to you more than the other?

6. Lessons from this retelling of a Japanese folktale

- What insights or lessons did you gather from this? Reflecting on the narrative, were there any particular morals or messages that stood out to you? What did you like best about this tale? If you were the author, how would you end this story?

Things to discuss in class:

1. Significance of the crane (tsuru) in Japanese culture

a. Symbolism of the crane

-

- The crane holds significant symbolism in Japanese culture, often representing longevity, beauty, and grace. A traditional saying, “Tsuru wa sen-nen (crane lives one thousand years),” alongside “Kame wa man-nen (turtle lives ten thousand years),” reflects that the crane and turtle symbolize longevity. This symbolism is often depicted in wedding gowns featuring crane designs due to their association with long life and beauty.

b. Conservation efforts

-

- Historically, cranes were abundant in rice fields. With industrialization in the late 1800s, their population declined drastically, and they were in danger of extinction by the 1920s. Ongoing conservation efforts, including professional breeding in sanctuaries and zoos, have gradually increased their number, addressing environmental concerns.

c. Symbolic origami

-

- From the Edo period (1603–1868) onwards, crane origami (ori-zuru, folded crane) became a symbol of peace, happiness, health, and safety. Strings of a thousand origami cranes are used to advocate for peace without nuclear weapons, a legacy initiated by Sasaki Sadako, a victim of the Hiroshima atomic bomb during World War II.

ο Discussion Questions:

i. Do you know of any other Japanese folktales featuring a crane?

ii. In popular culture, such as anime, manga, or films, have you encountered depictions of cranes?

iii. Is there an American counterpart to the Japanese crane, symbolizing beauty and longevity? For examples, hawks, eagles, or swans? For example, how is the eagle represented in American culture?

iv. Are there any songs or folktales in your culture that center around an animal similar to the crane?

v. If you were the author, which other animals would you consider using as the protagonist in a story like this?

2. Significance of weaving in Japanese culture

a. Weaving in Shinto beliefs

-

- In Shinto, the indigenous Japanese faith, where nature is believed to be full of spirits, weaving silk holds a sacred significance. During Shinto rituals, weaving silk to create kimono cloth, along with singing and dancing, is considered crucial for offerings to the gods.

b. Understanding the importance of weaving

ο Discussion Questions:

i. Why do you think “weaving,” “clothes (kimono),” or “making cloth” holds such importance? Are the gods in your culture pictured wearing clothes?

ii. In your culture, what symbolism is associated with weaving silk or creating clothes? Are there any stories or traditions revolving around weaving, knitting, or spinning?

3. Significance of taboos — “Do Not Look”

a. Taboos and their impacts

-

- In the narrative, Hiroko retreats into the weaving room and instructs Yasuhiro and Ryota not to look inside until she completes her task. The concept of “do not look” represents a common type of taboo often found in Japanese folktales. Freudian theory suggests that taboos arise as societal tools to manage primal instincts, fostering order and moral standards.[1] In these tales, one’s identity, including physical appearance or name, remains concealed to maintain the magic. However, breaking such promises, as seen when Ryota breaches the agreement—looking inside the room and discovering the crane instead of Hiroko—disrupts the magic. This narrative underscores the significance of honoring promises, with serious consequences following their breach.

ο Discussion Points:

i. Exploring taboos in stories

-

-

-

- Can you recall other stories featuring taboos, such as “do not touch,” “do not speak,” “do not peek,” “do not eat,” or “do not go”?

-

-

ii. Understanding the purpose of taboos

-

-

-

- Why do you think people establish taboos? Is it feasible to maintain them consistently? What typically occurs when taboos are breached?

-

-

iii. Lesson on keeping promises

-

-

-

- What does this story teach us about the significance of honoring promises?

-

-

iv. Taboos in society

-

-

-

- In our society, do you think taboos, rules, restrictions, and promises should be preserved? Why do you believe such regulations or commitments were established in our culture?

-

-

4. Significance of On (obligation or indebtedness)

a. Sense of obligation

-

- The feeling of obligation (on in Japanese) arises when someone extends kindness, creating a strong sense of indebtedness and commitment to reciprocate the goodwill received. In this tale, Hiroko, the crane, feels compelled to repay the kindness shown by Yasuhiro, who saved her life.

ο Discussion Points:

i. Personal experience of obligation

-

-

-

-

- Can you recall a time when someone’s kindness led you to feel a strong urge to reciprocate or feel indebted to that person?

-

-

-

ii. Observing animal gratitude

-

-

-

-

- Have you witnessed animals expressing a sense of obligation or gratitude toward you or others?

-

-

-

b. Repayment through sacrifice

-

- Hiroko attempts to repay her obligation by weaving silk cloth for Yasuhiro and Ryota to sell, helping to supporting them. To honor her debt, she sacrifices her own health by plucking her feathers, intertwining them into the cloth.

ο Discussion Points:

i. Nobility versus sacrifice

-

-

-

-

- Repaying obligations through favors is noble, yet Hiroko’s extreme sacrifice might seem too extreme or risky. Do you perceive what she does as an act of beauty, as some Japanese readers might? Or do you think she was foolish to sacrifice her own well being, and naive to be taken advantage of by Ryota?

-

-

-

ii. Encountering sacrificial acts

-

-

-

-

- Have you encountered other stories where characters engage in sacrificial acts? What were the circumstances prompting such sacrifices?

-

-

-

c. Impact of broken promises

-

- Hiroko’s obligation ends when Ryota breaks his promise, revealing her true form as a crane.

ο Discussion Points:

i. Boundaries of obligation:

-

-

-

- Considering Hiroko’s extensive help with chores and silk weaving, when do you believe her obligations should have concluded?

- Or do you believe that you can never repay someone for saving your life?

-

-

5. Significance of money

a. Shift in Ryota’s attitude

-

- Initially, Ryota sets strict conditions for Hiroko’s stay, emphasizing hard work and honesty. The story takes a turn when the sale of the silk cloth brings Ryota substantial wealth, leading to a change in his attitude and revealing his greedy nature.

ο Discussion Questions:

i. Why do you think triggered this shift in behavior?

ii. How much money do you believe would have sufficed for Ryota or Yasuhiro to live comfortably?

b. Understanding greed

ο Discussion Questions:

i. How would you define greed? Are there distinctions between good and bad types of greed? Can you recall other stories that explore human greed, such as How the Grinch Stole Christmas by Dr. Seuss or A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, featuring the miser Ebenezer Scrooge?

ii. How much money do you believe would have sufficed for Ryota or Yasuhiro to live in peace?

c. Fate of Ryota

ο Discussion Questions:

i. What fate befalls Ryota in the end?

ii. Do you perceive his ultimate outcome as justified?

iii. Why or why not?

6. Reflections on the story

a. Permanence of goodness

-

- Does this story suggest that “good things” and “happiness” endure indefinitely?

-

- How do you define “happiness” in this story?

b. Hashtags for the story

-

- What hashtags would you assign to this story? For instance: #kindness, #friendship, #compassion, #respect, #nature, #poetry, #animals, #love, #empathy, #gratitude, #greed, #folktales, #crane, #transformation, #promise, #taboo, #happyending, etc.

c. Key lessons

-

- What key lessons or takeaways do you believe this story imparts?

d. Kindness and reciprocity

-

- Do you believe that performing acts of kindness towards others, including animals and nature, leads to future benefits?

e. “Pay It Forward” concept

-

- How does the concept of “paying it forward” resonate with this theme in the story?

f. Communication beyond language

-

- Despite different languages, can humans and animals communicate through a heart-to-heart connection?

g. Human-animal bonds

-

- Can humans and animals forge genuine friendships?

-

- Can both species support and understand each other despite differences?

Author: Yuko Eguchi Wright, Japan ethnomusicologist and Urasenke certified tea instructor; Kasuga School kouta master

2023

[1] Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo (Dover Editions, 2011; original publication 1913)

Archived Book Group The Crane Girl and Chibi Samurai Wants a Pet (Once you have created a login for yourself at asiaforeducators.org, you are able to view and access all current and archived offerings from the main page. One (free) login suffices for all).

Anne Izard Storytellers’ Choice Award

A New York Public Library Best Book of the Year

An Evanston Public Library Best Book of the Year