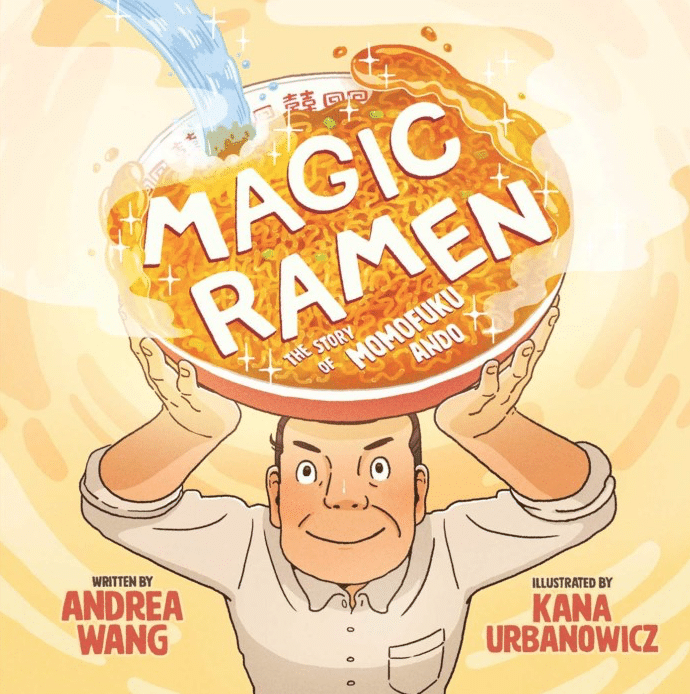

Magic Ramen: The Story of Momofuku Ando

- Non-fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: food, inventions, war, persistence

Inspiration struck when Momofuku Ando spotted the long lines for a simple bowl of ramen following World War II. Magic Ramen tells the true story behind the creation of one of the world’s most popular foods.

Every day, Momofuku Ando would retire to his lab—a little shed in his backyard. For years, he’d dreamed about making a new kind of ramen noodle soup that was quick, convenient, and tasty for the hungry people he’d seen in line for a bowl on the black market following World War II. Peace follows from a full stomach, he believed.

Day after day, Ando experimented. Night after night, he failed. But Ando kept experimenting.

With persistence, creativity, and a little inspiration, Momofuku Ando succeeded. This is the true story behind one of the world’s most popular foods.

Overview

How did instant ramen (pronounced: RAH-men) become one of the most popular fast foods on the planet? Magic Ramen by Andrea Wang illustrates the humble beginnings of instant ramen in the story of Momofuku Ando (1910–2007) (pronounced: mow-MOW-fu-ku AHN-dough) and his quest to feed the people of Osaka (pronounced: OO-sah-kah) after World War II.

Only a year after the war ended, Osaka was still in ruins. On his way home from work one day, Momofuku Ando came across a long line of people, cold and starving. They were waiting at a black market ramen stall. It took hours for them to get a single bowl of the noodle soup. Food was already scarce, and the few who were lucky enough to have some money had to pay a steep price for ramen. This moment stuck with Ando, so much so that he spent the next twelve years experimenting in his kitchen, trying to make a new kind of ramen. It would be fast to make and full of the nutrients Osaka’s people so desperately needed. Ando’s noodles would be “anywhere, anytime” noodles.

In 1958, Ando finally succeeded in inventing Chikin Ramen (pronounced: CHEE-keen RAH-men), the first instant ramen. As instant ramen caught on and Ando was able to lower production costs, instant ramen became affordable and widely available. People loved how quick it was to make, and eventually became a huge hit. Ando founded a company, Nissin (pronounced: KNEE-sheen) Foods, and today it distributes his ramen (and many other products) around the world.

Historical Context

Before Ando introduced instant ramen to the world, traditional ramen had already become popular across the nation. Originating in China, Japanese ramen was first developed in Chinatown in Yokohama. The word “ramen” was borrowed from the name for Chinese pulled noodles, or lāmiàn (pronounced: LAH-MEEyehn). However, ramen noodles are not actually pulled; they are cut, as they are in southern Chinese cities. This reflects the demographics of Chinese people living in Yokohama.

Southern Chinese noodle soups were topped with ingredients to suit Japanese tastes, which resulted in the ramen we know today. Broths such as soy, miso (pronounced: MEE-so; soybean paste), and tonkotsu(pronounced: tone-COAT-SUE); pork bone broth) are filled with noodles and topped with vegetables and pork or some other protein for a delightful meal. Yet the rise of ramen includes a rather dark chapter.

Since Osaka was a center of heavy industry in Japan, it was a strategic target for U.S. air raids. Over the course of World War II, with separate bombing raids decimated the city. Estimates put civilian deaths at over 10,000. As a result of the extensive firebombing, much of the city was reduced to rubble by the end of the war.

On top of the widespread destruction, Japan’s 1945 rice crop failed, resulting in food shortages nationwide. The United States, now occupying Japan, pumped the market full of cheap wheat flour—the primary ingredient in ramen noodles—in an effort to prevent mass starvation. Although much of the flour was used for bread, some was diverted from commercial mills by yakuza (pronounced: YAH-koo-zah; gangsters) and into the black market. Yakuza would provide flour to illegal ramen stalls and extort the vendors for protection money, since the Occupation authorities did not allow outdoor food stalls. Under these restrictions, ramen vendors were arrested by the thousands during the Occupation.

When the U.S. loosened vendor restrictions and wheat flour exchange was no longer controlled, ramen stalls grew in popularity. Today, ramen is a cultural icon and one of Japan’s most popular foods, synonymous with urban life.

Pronunciation Guide:

Akemi: AH-keh-mee

Koki: KOH-kee

Mahō no ramen: mah-HOE no RAH-men

Masako: MAH-sah-koh

Osaka: OO-sah-kah

Suma: SUE-mah

Tempura: TEM-poo-rah

Yatta: yah-TAH

Additional Resource

The Story of Nissin Cup Noodles: https://www.japan.travel/en/my/travelers-blog/the-story-nissin-cup-noodles/

Author: Evelyn Seitz, researcher and translator.

2024

In her second picture book, Magic Ramen: The Story of Momofuku Ando, Andrea Wang artfully describes the work behind the invention of instant ramen. This non-fiction story is set in Japan in 1946, only a year after the end of World War II. One evening after work Ando is walking home through Osaka when he sees people waiting in line for ramen noodle soup. The text on these pages is accompanied by powerful illustrations that clearly convey a city in ruins and the hunger of the people. Illustrator Kana Urbanowicz’s use of dark colors and careful attention to detail, such as the small clouds that form when people breathe in the freezing air, help readers to empathize with the cold, hungry people. When Ando arrives home, the mood of the illustrations becomes lighter, with more color and white space, but he looks determined as he works to find a way to feed the hungry.

Ando begins to develop inexpensive but nourishing food products, eventually focusing on instant ramen. His trial-and-error process is cleverly illustrated in manga-like panels showing each new attempt juxtaposed with its failed outcome. After Ando has success creating noodles, his persistence is again tested as he searches for a way to easily turn them into soup, depicted in another set of panels. Finally, Ando holds a bowl of noodles above his head, victorious, before a scene of cherry blossoms in full bloom. Wang explains how Ando’s whole family assists in preparing the ramen and shows Ando’s demonstration of the noodles for prospective customers.

Wang includes an author’s note to help readers understand the naming conventions used in the book, a pronunciation guide for names and terms readers encounter in the story, and an afterword to provide readers with more information about Ando. Readers can use this information as a starting point for additional research on the topic. Wang also enriches the story with several quotations from Ando himself. A bibliography with the sources of these quotations is available on her website.

In addition to being a focal piece of the book, Urbanowicz’s illustrations provide observant readers with several clues about the story as well. Even the book’s endpapers are an excellent example: the endpapers at the beginning of the book include the ingredients Ando used to make his noodles, while those at the end feature bowls and packages of noodles.

Magic Ramen is based on the universal theme of scarcity, more specifically the scarcity that occurs after war. This ties closely to the literary theme of survival, as Ando searches for a way to help meet the need for cheap but nutritious food. Wang’s text also incorporates the literary themes of perseverance, the quest for discovery, and, to a lesser extent, the importance of family.

This book provides many avenues for interdisciplinary exploration and numerous entry points for students. While the text is designed for readers ages four to eight, the illustrations and ideas will also appeal to students in middle school and high school, particularly as a wide variety of students will have eaten ramen.

One main theme, perseverance, is universally applicable to students. Students of all grade levels can identify with the trial-and-error process that Ando conducts before his success. Students can be asked to relate these experiences to goals and experiences in their own lives. Seeing how Ando learned from his setbacks can be used as a tool to help students reframe their setbacks as well.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, various types of foods were not available in grocery stores in the United States. Middle school and high school students are old enough to be aware of these scarcities. From a historical perspective, the scarcities of the pandemic can be compared to food scarcities in postwar Japan as students explore what items were scarce and the causes of the scarcity. From a science perspective, the lesson could explore nutritional guidelines and requirements for health in conjunction with the nutritional content of available foods. Language arts could be incorporated if students conduct research into other foods invented during times of scarcity.

Throughout the text, Ando participates in a design process, searching for the best ingredients and methods with which to create his noodles. This can serve as a springboard for students of all grade levels to explore the engineering design process in a science class or unit on food. Students could also try to make their own noodles or use media to learn more about the noodle-making process.

Social Studies Standards (C3 Framework)

- His.14.3-5. Explain probable causes and effects of events and developments.

- His.16.3-5. Use evidence to develop a claim about the past.

- Geo.11.K-2. Explain how the consumption of products connects people to distant places.

Science Standards (Next Generation Science Standards)

- HS-LS1-7. Use a model to illustrate that cellular respiration is a chemical process whereby the bonds of food molecules and oxygen molecules are broken and the bonds in new compounds are formed, resulting in a net transfer of energy.

- MS-LS1-7. Develop a model to describe how food is rearranged through chemical reactions forming new molecules that support growth and/or release energy as this matter moves through an organism.

- MS-ETS1-1. Define the criteria and constraints of a design problem with sufficient precision to ensure a successful solution, taking into account relevant scientific principles and potential impacts on people and the natural environment that may limit possible solutions.

- MS-ETS1-2. Evaluate competing design solutions using a systematic process to determine how well they meet the criteria and constraints of the problem.

- MS-ETS1-3. Analyze data from tests to determine similarities and differences among several design solutions to identify the best characteristics of each that can be combined into a new solution to better meet the criteria for success.

- MS-ETS1-4. Develop a model to generate data for iterative testing and modification of a proposed object, tool, or process such that an optimal design can be achieved.

English Language Arts Standards (Common Core State Standards)

- ELA-LITERACY.RL.5.7. Analyze how visual and multimedia elements contribute to the meaning, tone, or beauty of a text (e.g., graphic novel, multimedia presentation of fiction, folktale, myth, poem).

- ELA-LITERACY.RL.5.2. Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text, including how characters in a story or drama respond to challenges or how the speaker in a poem reflects upon a topic; summarize the text.

Author: Jennifer Smith, teacher of 7th and 8th grade language arts, Illinois Virtual School

2021

Teacher’s Guide, created by Anna Chan Rekate, 2019

Fill out the online form to access the NCTA webinar with author Andrea Wang

Junior Library Guild Selection

School Library Journal Starred Review

Smithsonian Ten Best Children’s Books of 2019

Center for the Study of Multicultural Children’s Literature (CSMCL) Best Books of 2019