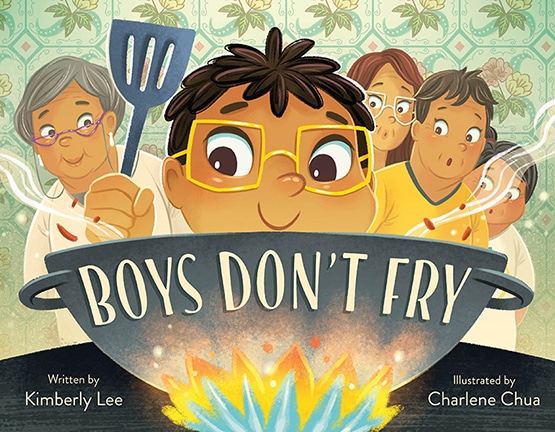

Boys Don’t Fry

(Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Macmillan Children's Publishing Group)

- Fiction

- Set in Malaysia

Key Words: Food, family, gender roles, Lunar New Year

It’s the eve of Lunar New Year, and Jin can’t wait for the big family reunion dinner. He loves the aromas and the bubbly chatter coming from the kitchen. His grandmother, Mamah, is cooking up a storm!

As his aunties dice, slice, and chop, there’s nothing Jin wants more than to learn about the history of his family’s cooking and to lend them a helping hand. After all, no one else can tell the difference between ginger and galangal as well as he can! But his aunties shoo him away, claiming he’ll just get bored or be in the way. Luckily, Mamah steps in and asks Jin to help her prepare their special meal. Soon, Jin is squeezing, slicing, and stirring, too!

This loving picture book about a young Malaysian boy who defies gender expectations will make hearts warm and stomachs hungry. With beautifully vibrant illustrations of a traditional nyonya kitchen, Boys Don’t Fry is a heartfelt celebration of family, culture, and traditions—both old and new.

…the kitchen was the stomach of the house.

—Boys Don’t Fry

Appropriate for Grades: K–6

Best for Grades: 3–8

Introduction to the Book

Food lovers rejoice. The pages of Boys Don’t Fry are laden with love for Peranakan cuisine. Even without the ability to pronounce, much less identify, many of the dishes described in the book, students will find their mouths watering at the food spread across the Lunar New Year banquet table. And although the through line of the story is the rather mature theme of gender roles in the kitchen, this truly is a picture book geared toward younger learners.

Best Matched Curricular Units

- International Cuisines (Social Studies)

- Cultural Interaction and Exchange (Geography)

- Gender Roles (Humanities)

Essential Questions

- What value do traditions bring a culture?

- How can food build relationships?

- Does food hold memory?

Suggested Activities

Cover Predictions. Before reading the book, examine the cover, using the images and the title to make predictions.

Print copies of the cover for the students, but add thought bubbles extending from each character. Ask students to fill in what they suspect the characters might be thinking.

Jin’s Mamah’s Kitchen and Yours. Pre-reading activity: Students draw the kitchens in their own homes. After they read the book, encourage students to look carefully at the objects and ingredients in Mamah’s home, and ask them to compare what they observe to their own kitchen at home. When they see an object, tool, or ingredient that is new to them in Mamah’s kitchen, research what it is and how it is used.

Ingredients. Fifteen ingredients are named and illustrated on the inside covers of the book. Students will probably be familiar with garlic, onion, and chili, but they likely have no experience with belacan, candlenut, or bunga kantan. This could lead to several activities:

- Ask each student to draw an ingredient unique to their own family’s cooking culture. Create a class collage of ingredients.

- Before learning about a new ingredient, ask students to predict the ingredient’s use and make up an imaginary dish that could highlight their ingredient. See if the book offers any answers before doing some online research.

- Play a game where students race to find each ingredient in the book—in either text or illustration.

- Search for recipes that use an ingredient that is new to them.

- Find out more about a new ingredient and try to describe its characteristics. Try to devise a substitution using ingredients they are familiar with and have easier access to. Discuss the limitations of making substitutions and consider a deeper discussion of culinary assimilation and its causes.

Lunar New Year Research. The Lunar New Year is the major holiday in East and Southeast Asian cultures (except for Japan, which celebrates New Year on January 1). However, it is celebrated differently from culture to culture. Have groups of students choose different Southeast or East Asian countries (principally Korea, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines) and learn about some of the culturally specific ways they celebrate the Lunar New Year. Then teach the class how Peranakan Chinese celebrate. Discuss the differences that students notice as well as what might cause those differences to emerge (geography, resources, politics, and more)

Culture-Specific Foods. In the story, the author exposes readers to many foods specific to Peranakan Chinese culture—pineapple tarts, chicken pongteh, laksa, salted plums, itek tim soup, rainbow-colored kueh, and so on. As a class, create a menu of foods specific to the students’ own cultures, and ask each student to create an introduction to a dish specific to their family’s culture. Draw the map outline for the dish’s country of origin. Then put a picture of the dish along with its name inside the map outline, and list some of the dish’s special ingredients. Hold a gallery walk where students can introduce their dishes to one another.

Try the Recipe. Have students ask their parents to try the recipe at the back of the book for Peranakan pongteh chicken. When students return to school, they can share whether their parents were able to try the recipe and how it went. Ask those who tried the recipe to discuss their experiences (for example, did they have difficulty finding ingredients, were any steps in the recipe especially challenging, did they have to make kitchen tool substitutions, and how did their family like the food?). Regardless of how many students were able to try the dish at home, this should create a rich discussion about obstacles to experiencing other cultures’ cuisines and what we learn and gain when we do get to experience them.

Suggested Discussion/Writing Prompts

Tradition vs. Change. Should traditions be maintained, or should we let them go in the name of progress? What is lost when we give up traditions? What is gained? Which is more valuable?

Embracing Difference. When Jin offers to help in the kitchen, he challenges family and cultural norms. What or who gets in the way of this challenge? How does Jin overcome the obstacles? Can you think of a time in your own life when someone challenged a social norm? What did they need in order to succeed in the challenge? Is there ever a time when people should not challenge social norms?

Kitchen as Stomach. Jin’s Mamah uses a metaphor to compare the kitchen to being the stomach of the house. Certainly, food comes out of the kitchen and then goes into the family’s stomachs. But if the kitchen itself is the stomach, then what else is going into and coming out of the kitchen besides ingredients and food? What does a stomach do for the body? Extend the metaphor, paying special attention to what Jin gains from his time with Mamah in her kitchen.

Special Ingredient. The final sentence of the story says that Jin filled every dish with “sweetness, spice—and that very special ingredient.” What do you believe that very special ingredient actually is? Is that ingredient as essential as sugar or spices when cooking food for family?

Recipe Secrets. In the “Author’s Note,” Kimberly Lee tells us that in Peranakan culture, family recipes are often “guarded fiercely.” Yet on the following page, she shares her own mother’s pongteh chicken recipe. How do you think her mother would feel about having her prized recipe published in a book? Do you think recipes should be kept as family secrets, or should they be shared with others?

Author: Josh Foster, Educator and Learner

2025

Honor Winner for the The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) 2024 Crystal Kite Award for region: Middle East & Asia Division