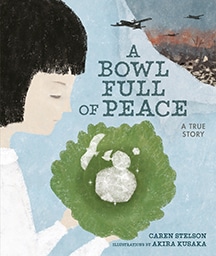

A Bowl Full of Peace: A True Story

- Non-fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: Nagasaki, biography, war, family, death

In this deeply moving nonfiction picture book, award-winning author Caren Stelson brings Sachiko Yasui’s story of surviving the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and her message of peace to a young audience.

Sachiko’s family home was about half a mile from where the atomic bomb fell on August 9, 1945. Her family experienced devastating loss. When they returned to the rubble where their home once stood, her father miraculously found their serving bowl fully intact. This delicate, green, leaf-shaped bowl—which once held their daily meals—now holds memories of the past and serves as a vessel of hope, peace, and new traditions for Sachiko and the surviving members of her family.

There are many powerful symbols of the atomic bombing of Japan—for example, the mushroom cloud, long strands of origami cranes, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (also known as the Atomic Bomb Dome). In this text, Caren Stelson introduces a new symbol to this pantheon: a green porcelain serving bowl. The story centers on young Sachiko (pronounced: SAH-chee-koh), her family, and her grandmother’s porcelain bowl. As a child, Sachiko gathers with her family for dinner, the bowl in the middle of the table filled with delicious foods such as squid, eel, octopus, and udon noodles. Before each meal, everyone bows their head and says itadakimasu (pronounced: ee-TAH-DAH-KEY-mah-sue), as people in the West might say grace or bon appétit.

A Bowl Full of Peace follows Sachiko’s family over roughly fifty years, from approximately 1943 to 1995. In the early pages of the book, Sachiko’s family faces increasing difficulties as U.S. military forces converge upon the Japanese empire and their hometown of Nagasaki. The bowl remains a fixture on the dining table, but its contents grow increasingly sparse. Toward the end of the war, the bowl contains only wheat balls in a thin broth. Nevertheless, they start each meal by bowing their heads and saying itadakimasu.

On the morning of August 9,1945, Sachiko and her siblings are playing outside when the atomic bomb explodes. Her little brother Toshi is immediately killed in the blast. The rest of the family hurries home to discover that their house has been destroyed. Over the next days, months, and years, Sachiko’s family members suffer from radiation poisoning. Ice chips are one of the rare treats used to soothe their burning throats.

After two years, the family excavates what remains of their home only to discover grandmother’s green porcelain bowl buried under the rubble, but undamaged.

For the rest of their lives, Sachiko’s family members gather every year on August 9 to eat ice chips out of grandma’s bowl in remembrance of their suffering and loss. As the years pass, most of Sachiko’s family members die of radiation sickness, and the annual ice bowl tradition becomes increasingly significant. Each time they gather to eat the ice, they bow their heads and say itadakimasu.

Written for elementary school students, A Bowl Full of Peace contains many powerful themes. Each can serve as a potential lesson topic for a history class, literature class, or even art class. The most obvious theme involves the Japanese word itadakimasu. Said at the start of a meal, it can be translated literally as “we humbly receive this food.” And yet as Sachiko’s story progresses, the phrase becomes much more significant. It conveys gratitude but also acceptance of their fate. Many elementary students will pick up on these nuances throughout the story and be able to identify similar rituals in their own lives that take on added significance in certain situations (such as holiday dinners, graduation ceremonies, and funerals).

Another theme revolves around childhood innocence and victimization. While Sachiko increasingly hears the “clanging of hammers building torpedoes” throughout the early 1940s, for the most part she and her family are depicted as bearing no responsibility for the war. Instead, they are innocent victims. While it might be more challenging to help elementary students make judgments regarding the individual’s responsibility during wartime, they do have a developing sense of fairness and justice. The story doesn’t necessarily provoke such questions, but a skilled teacher can help students start to reflect, unpack, and analyze these ideas. If we are ever to achieve the sort of peace that this book promotes, we must move past a fixation on victimization and be willing to ask tough questions about responsibility and aggression. Certainly all participants in World War II engaged in questionable actions and bear responsibility for the tragic events.

Still another theme touches on relics and mementos. The green porcelain bowl represents different things at different times, but it remains a powerful symbol throughout. Upon discovering the bowl in the rubble of their former home, Sachiko points out that “everyone has eaten from it,” even those family members who have already died. “The bowl had the fingerprints of all the members of her family on it,” the text reminds us. It might be useful to ask students to identify relics and mementos in their own families and ask what makes them so meaningful. For the most part, we associate relics with religious or spiritual significance. Is it possible for mundane personal objects such as a bowl to acquire religious or spiritual significance?

Finally, the story introduces the theme of long-term suffering and trauma associated with war. Only one of Sachiko’s family members dies immediately as a result of the bomb, yet the family suffers physical and psychological effects for over fifty years, passing that trauma down to later generations. (Teachers can decide if the Disney movie Encanto might be an interesting comparison for their students to understand intergenerational post-traumatic stress.) It would be helpful for students to understand that the survivors of the atomic bombs—known in Japanese as hibakusha (pronounced: he-BAH-KU-shah)—were shunned in Japan for decades after the war. They were seen as polluted and potentially dangerous. Japanese employers and politicians routinely discriminated against the hibakusha, and many remained single for the rest of their lives as no one wanted to marry them.

The author of the text, Caren Stelson, does an admirable job of sharing Sachiko Yasui’s powerful story. Similarly, illustrator Akira Kusaka provides moving and emotional images. Stelson has written two books about Sachiko; the other, titled Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story, is geared toward middle and high school students. Elementary schoolteachers might direct more advanced students to this companion volume. Regardless of the approach used in the classroom, Sachiko’s story is powerful and needs to be shared.

Author: David Kenley, Dean of the College or Arts and Sciences, Dakota State University 2023

Reading Level- 4 Accelerated Reader 3.6

Lexile- 650 Dewey- 940.54

Summary: A Bowl Full of Peace is a beautifully illustrated book about a Japanese family whose traditions are stronger than the harsh realities of the world. The book takes place prior to WWII in Nagasaki, Japan. The story follows the family through the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and afterwards for almost fifty years.

Vocabulary: (All vocabulary definitions are from dictionary.com)

Cicadas: noun, plural ci·ca·das, ci·ca·dae (Pronounced : si-key-dee, –kah-)

any large homopterous insect of the family Cicadidae, the male of which produces a shrill sound by means of vibrating membranes on the underside of the abdomen.

Udon Noodles: noun, plural u·don (Pronounced : oo-DOHN)

a thick, white Japanese noodle made from wheat flour, often served in soup.

Torpedoes: noun, plural tor·pe·does

a self-propelled, cigar-shaped missile containing explosives and often equipped with a homing device, launched from a submarine or other warship, for destroying surface vessels or other submarines. Any of various submarine explosive devices for destroying hostile ships, as a mine.

Mackerel: noun, plural (especially collectively) mack·er·el, (especially referring to two or more kinds or species) mack·er·els

a food fish, Scomber scombrus, of the North Atlantic, having wavy cross markings on the back.

Atomic Bomb: noun, A·tom·ic Bomb

a bomb whose potency is derived from nuclear fission of atoms of fissionable material with the consequent conversion of part of their mass into energy.

a bomb whose explosive force comes from a chain reaction based on nuclear fission in U-235 or plutonium.

Radiation: noun, ra·di·a·tion (Pronounced rey-dee-ey-shuhn)

- Physics

- the process in which energy is emitted as particles or waves.

- the complete process in which energy is emitted by one body, transmitted through an intervening medium or space, and absorbed by another body.

- the energy transferred by these processes.

- the act or process of radiating.

- something that is radiated.

Rubble: noun, rub·ble (Pronounced: ruhb-uhl)

- broken bits and pieces of anything, as that which is demolished: Bombing reduced the town to rubble.

- any solid substance in irregularly broken pieces.

- rough fragments of broken stone

Universal Theme: The universal theme of this book is about the sharing of experiences to prevent future repetition of history.

Literature Themes that are represented in A Bowl Full of Peace

- Good vs Evil

- Facing Darkness

- Power of Tradition

- Darkness and Light

- Displacement

- Everlasting Love

- Family blessing

Higher Level Questioning

REMEMBER: (Level 1) Recognizing and Recalling

- List the main events that happen in the story in order from beginning to end.

- Who were the family characters in the story?

- Describe what happened when the bomb hit Nagasaki.

UNDERSTAND: (Level 2) Interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, explaining

- What can you infer from the pages (18 and 19) depicting the bombing that have only illustrations and no words?

- How would you express the significance of finding grandma’s bowl when their entire house was destroyed?

- Compare and contrast the contents of grandmother’s bowl as the story progresses from peacetime to wartime.

APPLY: (Level 3) Executing and implementing

- What examples can you find to show the importance of the bowl to the family?

- How would you develop a plan of what you could possibly take with you if you had to evacuate because of a war?

- How would you demonstrate a way to keep one of your family traditions alive?

ANALYZE: (Level 4) Differentiating, organizing, attributing

- How would you explain the significance of the fact that everyone in the family, dead and alive, had touched the bowl?

- Why do you think the author used the bowl in the story to represent family tradition?

- How can you compare the melting ice in the bowl to what happens to their family as the story progresses?

EVALUATE (Level 5) Checking and critiquing

- How did the illustrator portray the difficult times versus the good times in the drawings?

- Predict the outcome if the bowl had not survived.

- What facts can you gather about the effects the radiation had on the people in Nagasaki?

CREATE (Level 6) Generating, planning, producing

- Determine the value of the bowl to the family.

- What choice would you make fifty years after the war had ended to ensure that such a terrible thing didn’t happen again? What did the author do?

- What is the most important lesson in this story? Why?

Research websites

https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/atomic-bomb-history

https://www.britannica.com/technology/atomic-bomb

https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/bombing-of-hiroshima-and-nagasaki

Standards

Elementary

Language Arts – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy

Math – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/Math/

Social Studies – Standards: https://aos98.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/ncss-standards.pdf

Middle Grades

Language Arts – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy

Math – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/Math/

Social Studies – Standards: https://aos98.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/ncss-standards.pdf

High School

Language Arts – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy

Math – Standards: http://www.corestandards.org/Math/

Social Studies – Standards: https://aos98.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/ncss-standards.pdf

Activities

- Have students illustrate a story about a tradition they may have in their family.

- Have students research the bombing and the effects radiation has on a person’s body.

- Have students calculate the distance between Nagasaki and their hometown.

- Have students research and calculate the distance the effects of radiation were felt and what some of those effects were.

- Have students create their own family vessel to represent themselves.

- Have students write about how they would feel if their family went through this bombing. Students would need to use textual evidence in their reasoning.

Author: Meredith Lesney, Middle School Librarian/Author

2020

2020 Nerdies: Best Nonfiction Picture Book

Kirkus Best Children’s Books, Winner, 2020

Chicago Public Library Best of the Best Books, Winner, 2020