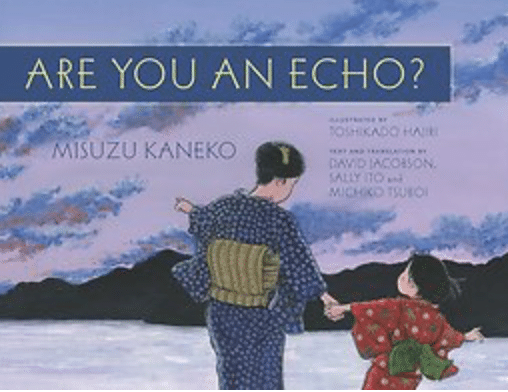

Are You an Echo?

- Non-fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: verse, translation, family, suicide, tsunami, nature

Are You an Echo? brings the lyrical poems and life story of now famous Japanese poet, Misuzu Kaneko, to an American audience. Her poems were lost for many years but are now popular with schoolchildren throughout Japan. The haunting title poem was played instead of commercials on public radio after the tsunami in 2011, helping to bring a million volunteers to the devastated seaside towns. Her poems capture Kaneko the thoughtful child observing nature and life by the sea and, later, the loving mother. Illustrations by Toshikado Hajiri complement the biography as recreated from Kaneko’s diaries and her vivid poems. Even the tsunami and recovery are powerfully depicted. The poems, several printed in English and Japanese, are aimed at young readers. Encountering Kaneko’s illness and suicide will require guidance from parents and teachers, though, but current scholarship on early childhood education suggests that children are strengthened by seeing both darkness and light in life.

Are You an Echo? recounts the life of a prolific young Japanese poet of the 1920s who wrote under the pen name Misuzu Kaneko (Misuzu is her family name). The book, which takes its name from one of Misuzu’s best-known poems, is interspersed with selections of her poetry. The following sections offer some background history and other contextual cultural information.

Setting and Time Period: Rural Japan in the Taishō Period

Misuzu Kaneko lived in the rural seaside village of Senzaki, on the Sea of Japan, from 1903 to 1930. Her life spanned the last years of Japan’s Meiji period (1868–1912), the years of the Taishō period (1912–1926), and the first years of the Shōwa period (1926–1989), all named for the emperors who ruled during those years. The early 1900s was a period of rapid social, economic, and political change in Japan.

For women, some important social and economic changes took place during a flowering of liberal and democratic ideas in the Taishō period. In the 1920s, women living in Japan’s growing urban centers enjoyed new freedoms. But these changes would have been felt in Misuzu’s small village to a much lesser degree. While women in urban areas were experiencing new employment opportunities, freedom to pursue fashion trends, and some expansion of social roles, the Japanese government was also actively promoting the traditional societal roles for women as “good wives and wise mothers.” These responsibilities had become part of government-instilled national values during the Meiji period and were furthered as national ideals in the Taishō period and later. Women’s proper role in Japanese society, according to the national government, was to serve their husbands, supervise their children’s education, and manage household affairs. It should be noted that while this ideal of full-time wife and mother might be attainable by women in the upper and upper-middle classes, many women in both urban and rural settings needed to work. This reality is reflected in Misuzu’s own family, with her widowed mother’s employment in a village bookstore. At the same time, this biography reflects some of the ways Misuzu benefited from the Taishō-period expansion of education and her mother’s thinking about women’s roles.

Education in the Meiji and Taishō Periods

A priority of the Meiji government (1868–1912) was education, considered one pillar upon which Japan’s transition to a modern nation-state rested. The Meiji-period government instituted a public education system. By 1907, six years of elementary education was compulsory throughout Japan. By the time Misuzu was finishing her primary education, Japan had one of the highest literacy rates in the world. According to the Japanese government, primary school attendance was about 96% by 1912.

Are You an Echo? notes that “Nearly all Japanese girls in the early 1900s stopped going to school after sixth grade.” In fact, through the Taishō period, formal education for most Japanese children—boys as well as girls—ended after six years. During this time, few government-supported middle schools existed in Japan, and there was no requirement to attend middle school. Additionally, rural areas were often unable to support middle schools. Academic middle schools that did exist would typically have been restricted to boys. Middle school options for girls typically focused on training girls to fill their role in society, emphasizing domestic duties. Are You an Echo? is unclear on whether Misuzu went to this kind of school for another six years or to a more academic school.

Divorce and Child Custody

The Meiji Constitution of 1887 noted the right to sue for divorce, but divorce initiated by women was rare in practice. It did not become a guaranteed right until the postwar constitution of 1947. During the Taishō and early Shōwa periods, child custody would customarily have been granted to the father following divorce. As the story indicates, it would have been difficult and unusual for Misuzu to have won custody of her child unless her husband refused it. Family law was significantly revised under the postwar Occupation, and a new Japanese Civil Code came into effect in 1947. With this code, the law dictated that mothers receive custody of children in a divorce. Joint custody was not recognized until the Japanese Diet passed a revision to the Japanese civil code in 2024.

Shintō Beliefs

The author notes, “To Misuzu, everything was alive and had its own feelings—plants, rocks, even telephone poles” (p. 12). This feeling may be closely associated with Japan’s indigenous belief system, Shintō (“the way of the gods”). Young readers may benefit from some background on Shintō ideas. One of the core beliefs of the Shintō faith is that everything possesses a spiritual essence or energy called kami. Mountains, rivers, places, animals, and people are all said to have a spiritual essence, though some people define kami as supernatural entities rather than spiritual energy. Misuzu would not have been unusual in believing that all things, even inanimate objects, possess an energy or spirit, as this is a fairly common idea within the Shintō faith.

Trigger Warning: Sensitive Topics for Young Readers

The author and translators note that this book directly addresses two sensitive issues in Misuzu’s life. The story notes that Misuzu caught a disease from her husband (p. 16). While the sexually transmitted disease is not named, this information may be alarming to young readers. Children might ask what disease Misuzu caught from her husband and how. The story also discusses Misuzu’s suicide (p. 20). Teachers using this book in the classroom should be prepared with strategies to address these issues in the narrative.

The 3/11 Triple Tragedy

The author notes that Misuzu’s poetry was little known in Japan until years later, when her brother revealed her story. Her poems took on new life and significance after the “Triple Disaster” of March 11, 2011, in Japan. The Triple Disaster was initiated by a catastrophic 9.1 magnitude earthquake in the Pacific Ocean about 45 miles off the coast of northern Honshu, Japan’s main island. It was the worst recorded earthquake to ever hit Japan. The earthquake, in turn, caused a massive tsunami (tidal wave) to slam northern Honshu’s Tōhoku (pronounced: TOE-HO-koo) region. These two events contributed to a nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daichi nuclear power plant. Thousands of homes, businesses, and much of the infrastructure in northeastern Japan were destroyed. Although reports differ, it is estimated that more than 15,000 people died in 3/11, and more than 450,000 people became homeless.

In the aftermath of these three events, Misuzu’s poem “Are You an Echo?” was broadcast through public service announcements throughout Japan, along with other messages of hope. The author notes that many in Japan read the poem as a call to volunteer to help those impacted by the 3/11 disasters. Misuzu’s poem is a vivid example of the power of poetry and the power of a single voice. While the author emphasizes the role of Misuzu’s poem in inspiring volunteerism, it should be noted that many factors contributed to a national, and global, outpouring of support for the victims of 3/11.

Sources

Cave, Peter. “Selective secondary education for girls,1900–1945.” University of Manchester. n.d.

Clark, Paul H. “Seinan Gakuin and Private School Education in Taishō Japan (1912–1926).” Politics, Bureaucracy, and Justice (3:2)

Hammer, Elizabeth. “Shinto: A Japanese Religion.” Asia Society. n.d.

Hoffman, Michael. “The Taisho Era: When Modernity Ruled Japan’s Masses.” Japan Times (29 July 29 2012).

Hong, Rebecca, et al. “Moga, Factory Girls, Mothers, and Wives: What Did It Mean to Be a Modern Woman in Japan during the Meiji and Taishō Periods?” University of Colorado Boulder, TEA Online Curriculum Projects, 2015.

National Geographic Society. “Mar 11, 2011 CE: Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami.” n.d.

Segal, Ethan. “Meiji and Taishō Japan: An Introductory Essay.” University of Colorado Boulder, TEA Online Curriculum Projects, 2015.

Author: Lynn Parisi, NCTA National consultant, NCTA Founding National Director (retired)

2025

NCTA webinar with David Jacobson