Want

- Fiction

- Set in Taiwan

Keywords: dystopia, inequality, environment, romance, LGBTQIA

Set in a near-future Taipei, Taiwan, that is imagined as plagued by pollution, a group of teens risk everything to save their city. Jason Zhou survives in a divided society where the elite use their wealth to buy longer lives. They wear special suits, protecting them from the pollution and viruses that plague the city, while those without suffer illness and early deaths. Frustrated by his city’s corruption and still grieving the loss of his mother who died as a result of it, Zhou is determined to change things, no matter the cost. With the help of his friends, Zhou infiltrates the lives of the wealthy in hopes of destroying the international Jin Corporation from within.

Jin Corp not only manufactures the special suits the rich rely on, but they may also be manufacturing the pollution that makes them necessary. Yet the deeper Zhou delves into this new world of excess and wealth, the more muddled his plans become. And against his better judgment, Zhou finds himself falling for Daiyu, the daughter of Jin Corp’s CEO. Can Zhou save his city without compromising who he is, or destroying his own heart?

Introduction to the Story

In this speculative fiction set in “Taipei in an alternate near future” where decades of rampant pollution wreaks havoc on the environment and public health, the population is divided into those who “have” (you 有) and those who are “without” (mei 沒). As protagonist Jason Zhou (pronounced: “joe”) explains in the opening pages, “This is what it meant to be you, to have. To be genetically cultivated as a perfect human specimen before birth—vaccinated and fortified, calibrated and optimized. To have an endless database of information instantly retrievable within a second of thinking the query and displayed in a helmet. To have the best air, food, and water, ensuring the longest possible life spans…” (pg. 3) Mei form the other 95%—who “want and are left wanting” for not only material wealth but also basic human needs—and have an optimal life expectancy of forty years. (pg. 3)

When it becomes evident that Jin Corporation—manufacturer of the customized smart gear on which all the you depend for safeguarding their health and well-being—systematically perpetuates environmental degradation in order to maximize profits, the teenage protagonists hatch a daring plan to dismantle this malicious corporate empire from within. Daiyu (pronounced: “dye-you”), the young woman the protagonists randomly kidnap in order to fundraise for their venture, turns out to be the scion of Jin Corporation and, eventually, love interest to Jason Zhou, the story’s first-person narrator.

The plot unfolds over several months and reveals corporate greed, political corruption, murder, deadly viruses, digital surveillance and cyber attacks, decadent lifestyles and grotesque excesses side by side with glaring poverty and fatal diseases, complex family histories, plus evolving friendships and budding romances. A multicultural cast of primary characters include: Arun and his mother Dr. Nataraj, who are Indian and fluent in Mandarin; Victor, who is Filipino; Jin Daiyu, Lingyi, and Jason Zhou, who are ethnic Chinese; and Iris, an orphan who is Taiwan-born and Asian.

Taiwan—relevant background

Today’s Taiwan is a multicultural society with nearly twenty-four million residents, a democratic government, and distinct identities that set the island apart from its neighbors. Its citizens include indigenous peoples who began populating the island millennia ago, ethnic Chinese whose families migrated from China’s mainland over the past few centuries, and recent migrants from Southeast Asia. Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien, and Hakka are the most widely spoken languages, and traditional Chinese characters are used in writing. English is prominent in signage and public announcements.

Geographically, Taiwan is an island located about 100 miles/161 kilometers from China’s southeastern coast. Human inhabitation on Taiwan dates to the Paleolithic Era, and archaeological findings suggest multiple sources of migration and confluences of cultures. As far back as 4,000 BCE, the island’s indigenous populations have been part of the Austronesian language family. Portuguese sailors dubbed the island “Formosa” in the 1500’s; during the first half of the seventeenth century, Dutch and Spanish traders established ports in southwestern and northern Taiwan, respectively. Although the Dutch dominated, they were driven out by the 1660’s, when China’s Ming Dynasty loyalists, escaping Manchu rulers (who founded the Qing/Ch’ing Dynasty in 1644) (pronounced: “ching”), fled mainland China and set up a base in Taiwan. In the subsequent two hundred-plus years, Taiwan remained an outlying, somewhat unruly, territory of the Qing empire. Most migrants from mainland China to Taiwan during this period were from the coastal Fujian province, and their mother tongue, Hokkien, gave rise to the local vernacular that became known as “Taiwanese.” Later, descendants of these early settlers were identified as benshengren 本省人 (natives; pronounced: “BEN-SHENG-ren”), differentiating them from the mid-twentieth century arrivals from China, and their descendants, commonly referred to as waishengren 外省人 (outsiders; pronounced: “WHY-sheng-ren”). In the twenty-first century, such identifiers are useful primarily for establishing historical context.

In 1895, Taiwan was ceded to Japan after China lost the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). Japanese colonial rule lasted fifty years, until Allied forces defeated Japan in World War II. China’s Nationalist Party (Guomindang/KMT) government then took possession of Taiwan, later imposing martial law that lasted for nearly four decades, during which all political dissent—perceived or proven—was systematically silenced through a campaign known as the White Terror. In the post-WWII years leading up to 1949, nearly two million Chinese from all over the mainland sought refuge in Taiwan as the KMT was losing the civil war to the Chinese Communist Party, which established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949. The KMT regime proclaimed Taiwan as the temporary headquarters of the Republic of China (ROC, founded in 1912), continuing observance of National Day on October 10 (Double Ten), and retaining international diplomatic recognition as the legitimate government of China until 1971.

The PRC continues to claim sovereignty over Taiwan as part of its national territory. Taiwan maintains “Republic of China” as its formal name and has a directly elected president as well as multiple political parties.

The English-language term “Taiwanese” has different connotations and, depending on the context, it might be: a reference to a spoken language or one’s personal identity; a signal of ancestry, birthplace, or residency; a declaration of political affiliation; or a hybrid of these identifiers.

Chinese language, naming conventions, and terms featured in this book

Chinese language consists of diverse spoken vernaculars, of which Taiwanese (a variation of Hokkien) is one. In its written form, Chinese comprises “characters” or Hanzi that appear in two versions: Simplified 汉字 is a modern format adopted in the mid-1900’s in the PRC and subsequently in Singapore; Traditional 漢字 is retained in Taiwan and Hong Kong to this day. [“Kanji” (漢字) used in Japanese writing is derived from Chinese Traditional characters with some modifications.]

Over the years, a number of romanization systems evolved to notate pronunciation of Chinese characters based on standardized spoken Mandarin, or Putonghua. Hanyu Pinyin (or Pinyin) currently is the most common and is used in Want with a notable exception: “Taipei” (which is based on Wade Giles system of romanization, rather than the Hanyu Pinyin Taibei) where the story takes place.

Chinese names begin with the family name followed by the given name, e.g. Jin Feiming (pronounced “jin FAY-ming”), the story’s archvillain and founder of Jin Corporation. His daughter’s given name, Daiyu (refers to jade and uncommon beauty), conjures the tragic heroine Lin Daiyu of The Dream of the Red Chamber, an iconic Chinese novel dating to the eighteenth century. The first-person narrator of Want is known only by his surname Zhou (sounds like “Joe” and written as “Chou” in Wade Giles) which assures the anonymity he desires (pg. 31). Zhou’s English-language name, Jason, only surfaces as he prepares to infiltrate Jin Corporation by posing as you. It is common for people in Taiwan to adopt foreign-language monikers while studying English or other languages, or when joining specific workplaces. Likewise, it is customary for teachers to assign Chinese names to students from other cultures learning Chinese language.

Key words used in the book to refer to the population groups:

有 You (pronounced: “yo”): to have.

沒 Mei (pronounced: “may”): without.

Perhaps coincidentally, the Pinyin spellings suggest an opposing binary of Us vs. Them (Mei vs.You) and create a visual impact that prompts the reader to sympathize—if not identify—with the have-nots.

金 Jin (as in the Jin Corporation and Jin Daiyu) (pronounced: dye-you) means “gold.”

Culinary morsels named in Taiwanese or Mandarin:

- Chua bing 礤冰 or 剉冰 (Taiwanese) shaved ice treat with sweet toppings (pg. 2).

- Chou doufu 臭豆腐 / 臭豆腐 (Mandarin) stinky tofu (pg. 4).

- Rousongbao 肉鬆包 / 肉松包 (Mandarin) brioche-style bun with pork floss (pg. 17).

A few places and practices mentioned in the story (in order of appearance)

Shilin 士林 (pronounced: “SHUR-lin”) Night Market (pg. 1) is an iconic venue for street food and shopping in northern Taipei. A veritable feast for the senses, night markets emerge in the evening as carts, stalls, and makeshift shopfronts open for business, and continue until the wee hours. Visitors can choose from a variety of quick meals, regional foods, snacks, drinks, as well as a wide range of merchandise such as clothing and accessories, shoes, music, stationery, appliances and other household goods, electronics, knickknacks, even pets. While there are many popular night markets throughout Taiwan, Shilin Night Market is perhaps the most famous among tourists and international travelers.

Yangmingshan 陽明山 (pronounced: “young-ming-shun”) (pg. 8) is a mountain range in northern Taipei named after the Ming Dynasty scholar Wang Yangming and home to Yangmingshan National Park (covering approximately 11,338 hectares) as well as private residences, several educational institutions, a former diplomatic district, and erstwhile American military housing. The Yangmingshan in Want, however, is deserted following apocalyptic transformations resulting from typhoons, a devastating earthquake, and fires. After kidnapping Daiyu at Shilin Night Market, Zhou transports her to his abode on Yangmingshan where he lives in an abandoned laboratory (pg. 13).

Longshan Temple[1] (Longshan Shi 龍山寺; pronounced: “lone-shun-SHUH”) (pg. 44) was originally constructed in 1738 to worship Guanyin, the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion and mercy. In the ensuing centuries the temple was rebuilt or restored numerous times following natural disasters, fires, or war-inflicted damage. Along the way, additions were made to house major deities in folk religion and Taoism/Daoism, including Mazu 媽祖 / 妈祖 the patron saint of seafarers (who is also known as: Heavenly Mother 聖母, Tian Fei 天妃, Tin Hau 天后). Today’s Longshan Temple is a vibrant center of spiritual and civic life, as well as a top tourist destination in Taipei. In Want, expressions such as “thank gods” or “my gods” reflect the plurality of deities in the popular pantheon.

Early in the story, Jason Zhou stops at Longshan Temple on Qingming (Ching Ming) Festival 清明節 (pg. 43) which is one of the four major observances in Han Chinese culture, along with Spring Festival (New Year), Dragon Boat Festival, and Mid-Autumn Moon Festival. Also known as Tomb Sweeping Day, Ching Ming Festival occurs fifteen days after the vernal equinox and typically falls on April 4 or 5.[2] In keeping with the practice of commemorating ancestors, Zhou burns incense in tribute to his deceased mother and the recently murdered Dr. Nataraj who was like a mother to him.

Liberty Square (Ziyou Guangchang自由廣場; pronounced: “ZUH-yo gwung-chung”) (pg. 158) was named in 2007 and refers to the outdoor plaza adjacent to the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial, National Concert Hall, and National Theater in downtown Taipei. Historically associated with public demonstrations and political protests ever since martial law was lifted in 1987, gatherings in this space often symbolize the democratic project in Taiwan. Although Jin Feiming’s announcement of a more affordable model of the protective suits (pgs.164-5) may appear benign in making the life-saving product accessible to more people, his ploy to release a highly contagious killer virus on that same occasion is both ironic and insidious.

[1] There are numerous other Longshan (or Lungshan) Temples; the one in this book is also known as Bangka Longshan Temple, Longshan Temple of Manka, or Mengjia Longshan Temple—all referencing 艋舺, the traditional name for Wanhua 萬華 / 万华, the district in Taipei where the temple is located. Diagram of the temple layout.

[2] Chinese traditional holidays are based on a lunisolar calendar system of which the Twelve Animals of the Chinese zodiac are components. In Want, Jin Daiyu was born in the Year of the Goat (pg. 302) which makes her a year younger than Zhou, born in the Year of the Horse. (pg. 12) In addition to the years they represent, the Twelve Animals also have corresponding time periods within each day and each month; for example, the rat represents the 11pm-1am interval that marks the beginning of a new day. In continuous use now for over two thousand years, the Chinese lunisolar calendar incorporates timekeeping systems embodying precise calculations based on centuries of meticulous recordings of astronomical phenomena.

Author: Rachel Wang, Kirkus reviewer; translator/writer

April 2022

The sci-fi drama Want, written by Cindy Pon in 2017, presents a dystopian future that seems eerily prescient in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic that began in late 2019. The book’s action, mystery, and excitement will surely appeal to YA readers. While it is important to present the novel as futuristic fantasy, it also opens up discussion of contemporary issues such as global public health, income inequality, and environmental justice. From the vantage point of educators of grades 7-12 and school librarians, the novel may best fit into the subject of Global Studies, an approach to history and social studies education that is growing in popularity for its more interdisciplinary way of teaching and learning about the recent past and current events. Even in more traditional English or Social Studies classes, the topics covered by the book can open up discussions about important twenty-first century global issues such as: Taipei as a global city and Taiwan as a gateway to the region, income inequality, environmental justice, and proposals for a better future.

Taipei as the Global City

Global Cities can be an entry point for a closer look into twenty-first century global issues in a Social Studies or Literature classroom. Global Cities will fit easily in the AP Human Geography curriculum but may also be incorporated into other independent social studies classes. Taipei may be considered a “global city” according to definitions presented by Professor of Geography Doreen Massey in her book World City. Massey notes that global cities may be defined by a “dominant foci in particular spheres of activity” (Massey, pg. 36). In other words, Taipei is not only an important financial center but also a center for facilitating the production of global products, exporting both technologies and culture. In addition, Taipei as the seat of government represents the strength and potential of East Asian democracy.

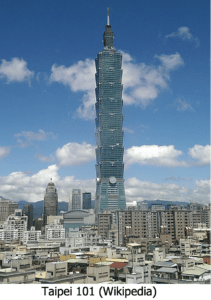

Students may also explore this symbolism with a closer look at Taiwan’s tallest building, Taipei 101. While this famous building is described in Want as a home to some of the characters’ posh condos, in fact the real building Taipei 101 is today a commercial building and not a residential one. It was the world’s tallest building for six years. The architect of this building, C.Y. Lee, said the building represented both Asian tradition and Western technology, and this blending is captured in the combination of Chinese motifs such as large discs that represent Chinese coins on an 8-segmented pagoda shaped façade with a cutting-edge technical design. In Chinese numerology, eight represents good fortune. Taken with the coins, the building—shaped like a Buddhist pagoda—conveys economic strength and prosperity. In East Asian history, beginning with Japan’s Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), technology has often been associated with the Western world since the Japanese borrowed much of its early modern technology from Western Europe and the United States. Perhaps these distinctions have grown passé. In the novel Want, Taipei represents the center of a battle between haves and have-nots, those with access to protective gear and those exposed to viruses and pollution. The Jin Corporation is the creator of cutting-edge technology but is also the purveyor of a laboratory-based deadly virus. The novel presents readers with a series of dichotomies, increasingly common features of life in the twenty-first century. Students will:

Students may also explore this symbolism with a closer look at Taiwan’s tallest building, Taipei 101. While this famous building is described in Want as a home to some of the characters’ posh condos, in fact the real building Taipei 101 is today a commercial building and not a residential one. It was the world’s tallest building for six years. The architect of this building, C.Y. Lee, said the building represented both Asian tradition and Western technology, and this blending is captured in the combination of Chinese motifs such as large discs that represent Chinese coins on an 8-segmented pagoda shaped façade with a cutting-edge technical design. In Chinese numerology, eight represents good fortune. Taken with the coins, the building—shaped like a Buddhist pagoda—conveys economic strength and prosperity. In East Asian history, beginning with Japan’s Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), technology has often been associated with the Western world since the Japanese borrowed much of its early modern technology from Western Europe and the United States. Perhaps these distinctions have grown passé. In the novel Want, Taipei represents the center of a battle between haves and have-nots, those with access to protective gear and those exposed to viruses and pollution. The Jin Corporation is the creator of cutting-edge technology but is also the purveyor of a laboratory-based deadly virus. The novel presents readers with a series of dichotomies, increasingly common features of life in the twenty-first century. Students will:

- Understand Taiwan’s place globally as a leader in technology and popular culture.

- Consider if healthcare, personal protective equipment, and vaccines should be a basic human right for all or a series of products for sale in the free market?

- Explain: “the tragedy of the commons” as it relates to the environmental degradation and pollution presented in the novel.

- Consider and explain the push and pull factors drawing migrants to Taiwan from neighbors such as the PRC and the Philippines.

Taiwan in World History and Economic History

In World History classes, study of the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), or Dutch East India Company, is central to modern economic global history. The Dutch rose to prominence in trade between Asia and the West when they colonized the area around present-day Tainan City in 1624. Due to its location along the busy sea routes between East Asia and Southeast Asia, fertile and resource-rich Taiwan served as an ideal base for VOC-controlled trade. During the 1630s, the VOC traded silk purchased from China and natural resources from Taiwan such as hemp and deer skin in exchange for silver from Japan. The Dutch purchased Chinese porcelain with the silver and then sold the porcelain to European markets along with natural resources from Taiwan (Tsai, 2016). The Maritime Asia: War and Trade online curriculum includes a lesson on the colonization of Taiwan.

Throughout its later history, under Chinese Qing (pronounced: “ching”) dynasty rule from 1863-1895 and Japanese rule from 1895-1945, Taiwan became a major grower and exporter of rice for Asia (Manthorpe, 2009). Post-World War II, Taiwan under Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) rule saw major land reforms and U.S. aid bolster its economy. Private sector development of new industrial technology paved the way for Taiwan’s rapid economic growth in the 1970s, known as the Taiwan Miracle. Today, Taiwan is at the forefront of the twenty-first century global economy, leading the world in the production of integrated circuits used in laptops and smartphones, the manufacture of high-end bicycles with carbon-fiber materials, and the invention of the globally popular bubble or boba tea (Rigger, 2014).

Income Inequality

A central theme of the novel is income inequality. While this topic may elicit strong feelings grounded in political ideology, it is important to note that income inequality is a

very salient feature of the twenty-first century, with common trends of a wealth gap between rich and poor throughout the globe. In fact, the novel takes the extra step of suggesting that this growing income inequality is creating literally two different types of human beings. Cindy Pon narrates: “This is what it meant to be you, to have. To be genetically cultivated as a perfect human specimen before birth—vaccinated and fortified, calibrated and optimized. To have an endless database of information instantly retrievable within a second of thinking the query and displayed in a helmet. To have the best air, food, and water, ensuring the longest possible life spans…” (pg. 3).

Students will:

- Come up with five to seven examples of how income inequality is depicted in the novel Want (the you and the mei) (pronounced: “yo” and “may” respectively).

- Conduct research to compare Taiwan’s growing income inequality with the U.S.’s and world-wide.

- Explain what challenges Taiwan faces in addressing income inequality and what strengths it possessesto address these challenges.

Environmental Justice

The novel also emphasizes the global “tragedy of the commons,” the way that individuals worldwide overuse our common resources and disregard how our collective action is contributing to polluted air and water, the loss of biodiversity, the degradation of the environment and contribution of greenhouse gasses to exacerbate climate change. Cindy Pon describes this future in Want: “The sky used to be blue. This is what my research on the undernet told me, some sites even displaying actual photographs from another time…I didn’t know anyone who had ever seen a blue sky” (pg. 18). Students will:

- Study, describe, and explain the theory of the “tragedy of the commons” using resources like a case study from Harvard Business School Online.

- Discuss three to five examples of the effects of pollution and climate change in the novel.

- Explain how the examples of environmental injustice contribute to the plot of the novel.

- Explore the website https://www.whatismissing.org, read and reflect on stories of something from the natural world that other contributors have witnessed diminish or disappear. Students can also share their own stories or examples of school or neighborhood conservation projects.

“Future We Want”

Cindy Pon describes a future of temporary physical enhancements and exceptional health as well as young lives lived in a metaverse of virtual reality. She writes, “They say money can’t buy happiness but those you kids try hard. They spend and spend. Then when things aren’t enough, they plug into the sim world so they can create and be whatever they want” (pg. 104). These topics are only partially fiction. With emerging technologies accessing the metaverse becoming more common, these topics are salient for student conversations. These topics encourage students to engage in philosophical and ethical thinking about the future they want, the future they think is good. In doing this, students begin to articulate values and make ethical judgments. Students will:

- Identify, explore and analyze their ethical values – Freedom, Diversity, Equality, Cooperation, Security, Justice, Self-reliance, Community, Stability, Democracy – from the Choices Program “Values and Public Policy” curriculum.

- Students will discuss three to five examples of “an alternate near future” in Taiwan. Is this future already here in some ways and are there good as well as bad aspects to it? What are some ways to act now to avoid the negative aspects of this alternate future?

Authors: Matthew Sudnik, Georgetown Preparatory School and Cathy Fratto, Asian Studies Center, University of Pittsburgh

April 2022

Paste Magazine’s Best YA Novel of 2017

A Junior Library Guild Selection