The Emperor’s Riddle

- Fiction

- Set in China

Keywords: mystery, adventure, family, countryside

Mia Chen is on what her mother calls a Grand Adventure (and a mystery adventure, at that). Mia’s not sure what to make of this family trip to China, and didn’t want to leave her friends for the summer. However, Mia is excited about the prospect of exploring with her Aunt Lin, the only adult whom she believes truly understands her. Then Aunt Lin disappears, right after her old nemesis, a man named Ying, comes to visit. Mia knows that years ago, when Aunt Lin and Ying were sent to the Fuzhou countryside to work as laborers, the two searched for an ancient treasure together—one that still hasn’t been found. She’s suspicious that their shared history might be linked to Aunt Lin’s disappearance.

When Mia discovers an old map filled with riddles in Aunt Lin’s room, she quickly pieces together her mission: find the treasure, find her aunt. Now, Mia, along with her big brother, Jake, must solve the clues to rescue the person she knows best in the world—and maybe unearth a treasure greater than her wildest dreams.

The Emperor’s Riddle provides an excellent entry point to China’s imperial and modern history, and an opportunity to discuss the Chinese diaspora. More broadly, it can allow us to talk about first and later generations of immigrants, their different experiences and views of the host country, and of their country of origin.

In the case of China, we must also consider its very long history. Even just from the twentieth century to the present, we find enormous differences in the motivations and backgrounds of immigrants from China. In the last two decades, many young, wealthy, and very well educated Chinese have decided to relocate to North America or Europe to expand their opportunities and enjoy more civil liberties. Throughout the mid-nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, however, the most common reasons to leave China were poverty and oppression. It was not unknown for a whole village to support a young person in going away, sometimes to a foreign destination, so that he (often it would be a young man) could work hard and eventually help his family and other villagers emigrate. The period of the California Gold Rush of 1849 is a prime example. In the recent past, four historical events prompted massive migrations:

- The Chinese Civil War (1927–1949) fought between the forces of the Guomindang (National People’s Party) (pronounced: GO-ming-dahng) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

- The second Sino-Japanese war (1937–1945) prompted by the Japanese invasion of China.

- The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and the retreat of the Guomintang to Taiwan.

- The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976).

Mia, the main character, lives with her Chinese immigrant mother and older brother in the United States. Early in the story, Mia, Jake, and their mother are visiting Aunt Lin in Fuzhou, their family’s ancestral home. Aunt Lin shows Mia a photograph taken when she was allowed to go home for the first time after three years of having been “sent down to the countryside” (p. 6). Mia imagines this as “a pretty exciting time,” something she would have preferred to sitting in school. But Aunt Lin is referring to the Great Proletarian Revolution, commonly known as the Cultural Revolution—a period of great hardship.

Mao Zedong (pronounced: MAH-oh ZEH-dohng), the Chairman of the Communist Party, was growing wary of pro-capitalist and bourgeois ideals gaining traction even within the party, and he unleashed a “purge” that resulted in millions of deaths and the implementation of a system of tight control of the citizenry. The Emperor’s Riddle briefly mentions some of the events that took place during the Cultural Revolution such as the destruction of “historic things” (pp. 148–149). The story makes it sound rather casual but, in truth, the destruction was massive, especially at Buddhist and Daoist temples. Many of those same temples are now being restored or rebuilt by the Chinese government. The human cost and the many ways the Cultural Revolution upended people’s lives are still being assessed. Students might also find it especially interesting to hear the voices of those, such as the fictional Aunt Lin, who were students then. In 2016, the New York Timesprinted testimonials of survivors from that period. Below is one of them:

Chen Qigang (pronounced: CHEN | CHEE-gahng), 64. Mr. Chen, a composer who now lives in France, was a student at a middle school in Beijing when the movement began. He spent three years in a re-education labor camp outside the city:

I have always been a very direct speaker. When the Cultural Revolution was starting, I spoke out about what I was seeing. The day after I said something, a big-character poster appeared on campus overnight: “Save the reactionary speechmaker Chen Qigang.” I was so young. I didn’t understand what was going on. Yesterday we were all classmates. How come today all of my classmates are my enemies? Everyone started to ignore me. I didn’t understand. How could people be like this? Even my older sister, who was also at my school, came to find me and asked, “What’s wrong with you?” You saw in one night who your real friends were. The next day I only had two friends left. One of them is now my wife.

At the time, no one really knew who was for or against the revolution. It was completely out of control. The students brought elderly people into the school and beat them. They beat their teachers and principals. There was nothing in the way of law. There was a student who was two or three years older than me. He beat two elderly people to death with his bare hands. No one has talked about this even until this day. We all know who did it but that’s the way it is. No one has ever looked into it. These occurrences were too common.

If there had been no Cultural Revolution, then I would not be who I am today. People who haven’t been through it can’t appreciate how easy everything else is. It wasn’t the manual labor. That’s a different kind of hardship. This was the worst kind of bitterness. You are constantly told: “You are against the revolution, so therefore you have no right to speak. You don’t have freedom. You will have no future in this place. You will not have a good job. Everyone looks down on you.”

That burden, that burden on your spirit, is very heavy. It was very different later when I went to France. I could have been criticized. I could have had a different opinion on something artistic. But for me that was nothing. It is nothing. Because it doesn’t affect my freedom. (New York Times, May 16, 2016)

The Cultural Revolution spread to the Chinese Communist Party itself. Thousands of CCP officials were purged, including such high-ranking officials as Deng Xiaoping (pronounced: DUHNG | SHAO-pin), who would be China’s top leader from 1978 to 1989.

Zhu Yunwen’s Treasure and the Architectural References

Zhu Yunwen (pronounced: JEW | YUHN-wuhn) was the second emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), known in the West for its blue-and-white porcelain, which was exported around the world. Zhu reigned for only four years (1398–1402) before being overthrown by one of his uncles. His uncle claimed that Zhu had been killed, but rumors circulated that Zhu had managed to escape. Stories of his escape were embellished over time. Some claimed he had disguised himself as a Buddhist monk, taken a great treasure, and hidden in temples and other places. The Emperor’s Riddle refers to these elements (pp. 17–18; p. 27), allowing the author to present a number of architectural jewels of Fujian (pronounced: FUH-gee-AHN). We encounter Buddhist temples, pagodas, and tombs.

Pagodas have a long history in Asia, and are often associated with Buddhism. The pagoda form—a tiered tower—can be traced back to an earlier form, the stupa, a type of shrine that predates Buddhism. Stupas were first built in ancient India as mortuary monuments to commemorate sages and kings by housing their relics or remains. To simplify, we might say that stupas were related to Hinduism (although this is a problematic statement) and were later adopted by Buddhists. With the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road, the stupabecame popular in South, Central, and East Asian kingdoms and empires. Each region transformed the stupaaccording to local preferences and tastes, so that it developed from a low, hemispherical domed monument in ancient India into a multistory building in China, often made of wood or stone and resembling a traditional Chinese watchtower.

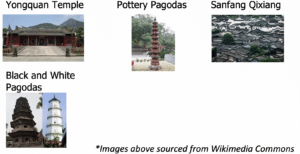

Fascinating legends connect individual pagodas to magnificent treasures or magic feats. The number of floors in a stupa is not random, as numbers in Chinese culture often take on special significance, and the size and height of buildings were regulated. In chapter 8, Mia discovers that one of the clues corresponds to “The thousand Buddha pottery pagoda,” which had nine levels. The number nine was associated with the emperor. At certain points in Chinese history, Buddhism was officially recognized and closely associated with imperial power. However, this pagoda also illustrates that, at other times, Buddhism was persecuted, and their temples and monasteries destroyed. “The thousand Buddha pottery pagoda” (or rather, pair of pagodas), built in the Song dynasty (960–1279) (pronounced: song) were housed within the Yongquan Temple. This temple was first built in 783 CE, during the Tang (pronounced: tahng) dynasty (618–907), only to be ordered destroyed by the Tang emperor, Wuzong (r. 814–846) (pronounced: wuu-TSONG) who unleashed the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution (841–845). Later, during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960) the king of Fujian ordered the reconstruction of the temple. Ultimately, it has suffered the ravages of time and natural disasters and has been repaired and rebuilt multiple times.

Chinese Language and Characters

Mia discovers what she believes to be Zhu Yunwen’s treasure map (p. 42). Beside the drawing of the map, she can make out some calligraphy. To Mia, this looks like “traditional, complex Chinese,” the kind she cannot read. This may be a good opportunity to introduce students to the evolution of language and a new family of languages: Sino-Tibetan.

The Sino-Tibetan family encompasses various dialects of spoken Chinese. The most common among these is Mandarin, spoken by more than 900 million people. The lingua franca among Chinese speakers is Standard Northern Mandarin (also known simply as Mandarin), which is used in schools, the media, and workplaces throughout the People’s Republic of China. In fact, it is the official language of mainland China, and one of the official languages of the United Nations. Mandarin is taught at most foreign schools and universities. In Chinese it is called putonghua 普通話 (pronounced: poo-TUNG-hwah), which means “the common language,” and is based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. The idea of a common language is very old in China, but putonghua refers to a standardized form of speaking that is quite recent.

The written language has a long and complex history: the earliest evidence of writing dates from the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) (pronounced: shahng); the first official standardization of Chinese characters occurred during the Qin dynasty (221–207 BCE) (pronounced: chin); and the most recent standardization took place after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. With the aim of encouraging literacy, Simplified Chinese was created. As compared to traditional Chinese writing, the simplified characters have fewer strokes. For instance, the character hua (of putonghua) is written 話 in traditional Chinese and 话 in the simplified form. One of the most striking examples of simplification is the verb ting (“to listen, hear, obey”) that was written 聽 and became 听 —going from twenty-two to only seven strokes!

Mia cannot read the calligraphy on the map, likely because the characters are written in the traditional Chinese form that she has not learned. The traditional form is still used in Taiwan, Macau, and Hong Kong, although the situation has been changing in Hong Kong and Macau since both reverted to Chinese rule (Hong Kong in 1997 from British rule, and Macau in 1999 from Portuguese rule).

Author: Margarita Delgado Creamer, PhD. Adjunct Instructor at the Department of Religious Studies, University of Pittsburgh

2021

Genre: Mystery Lexile: 780L

Pages: 256 Reading Level: 5.4

Perspective

This story is told from eleven-year-old Mia Chen’s point of view. Mia is an American whose mother was born and raised in China.

About the Title

The emperor in the title is Zhu Yunwen (pronounced: JEW YUHN-wuhn), who rose to the throne in 1398 at the age of twenty-one. His death remains a mystery even today. Yunwen was an ambitious ruler who wanted to increase the lands over which he ruled. Although he succeeded in conquering some nearby territories, he was eventually defeated in 1402 by his uncle, whose rule Zhu Yunwen threatened. The uncle’s troops burned Zhu Yunwen’s imperial palace, and it was said that he died in the fire. Another version of the story claims that Zhu Yunwen escaped and lived out his life in a monastery. The story’s protagonist, Mia, had ancestors who knew Zhu Yunwen. More information about Zhu Yunwhen can be found at this website: https://www.mingtombs.eu/emp/02jianwen/jianwen.html

The riddle refers to a treasure map combined with a series of clues that lead to a mythical treasure, said to have been hidden by Zhu Yunwen after fleeing the palace.

About the Author

Kat Zhang is an American author. Her parents are immigrants from China; her mother is from Fuzhou, and her father is from Wuhan. She began writing at a young age, and as of 2021, she had published both novels and picture books. More information about Kat Zhang can be found at her author website: http://katzhangwriter.com/index.php/about-me/

Recommended Audience

This book is ideal for middle readers (ages 8–12), particularly those who enjoy mystery and adventure, and students who want to learn more about Chinese geography and history. Additionally, this book might serve as a mirror for students who identify as Chinese American.

Curriculum Entry Points

| Entry Point | Teaching Suggestions |

| Aesthetic

|

Examine images of the historical sites mentioned in text. Use the see, think, wonder strategy to guide students as they examine and analyze the photos. See a list of historical sites visited by the book’s characters along with images below. Here is a link to a see, think, wonder strategy description: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/see-think-wonder. |

| Narrative |

Retell or have students read the legend of Zhu Yunwen. Here is a source for the story: https://www.mingtombs.eu/emp/02jianwen/jianwen.html. For additional perspectives, watch a video about Zhu Yunwen’s uncle who defeated him in 1402 at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XqxTJ91mS0. |

| Logical |

Recreate the emperor’s treasure map (as illustrated in the book) on poster paper. Share the first clue and ask students to share ideas about its meaning. Add to the map as students progress through the novel. |

| Foundational |

Survey the class or lead a discussion on the topic of legends. Is there truth in legends? Could these truths be relevant for us in the twenty-first century? Survey the class or lead a discussion on why authors write books. Look over Kat Zhang’s website and reflect on why she chose to write The Emperor’s Riddle. Here is a link to Zhang’s website: http://katzhangwriter.com/index.php/about-me/ |

| Experiential |

Have student create their own paper pagodas. This link provides instructions: https://www.education.com/activity/article/build-a-pagoda/ |

Specific Teaching Suggestions

Study Guide

A study guide can be found on the pages following this compilation of Curriculum Connections. The guide can be used by a teacher to preview the book. All or part of it might be distributed to students before, during, or after reading. The guide includes the following:

- Back of Book Summary

- Character Map

- Character Analysis

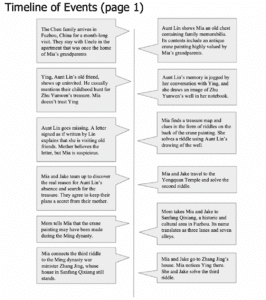

- Timeline of Event

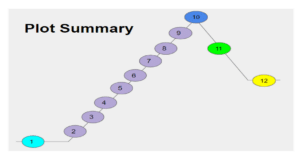

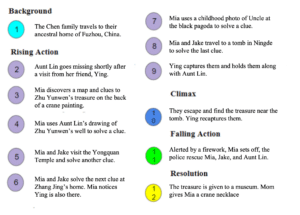

- Plot Summary

- Vocabulary List

- Riddles

Reading Suggestions

- Read Aloud or Whole Class Assigned Reading: While The Emperor’s Riddle can be read aloud or assigned to a whole class as independent reading solely on its literary merits, it is an ideal book to integrate with a social studies unit on China or East Asia.

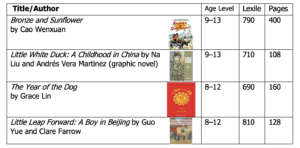

- Small Group or Book Club Reading Choice: The Emperor’s Riddle could be assigned as an enrichment activity for a small group of students. Similarly, it could be used for book clubs that are focused on Chinese culture. In addition to The Emperor’s Riddle, here is a list of book suggestions:

Writing/Storytelling Suggestions

- Zhu Yunwen went missing in 1402. If Kat Zhang’s story about a hidden treasure were true, how might Zhu Yunwen have gotten away with the treasure and created the map and clues? Create an original story to tell this tale. Share it orally and/or in writing.

Social Studies Suggestions

- The story is set in Fuzhou (pronounced: foo-JOE). Find Fuzhou’s location on a map of China, noting that it is located in Fujian (pronounced: FUH-gee-AHN) Here is a link to a commercial site from which an inexpensive tourist map can be purchased: https://trax2maps.com/fujian

- The emperor referred to in the title was from the Ming dynasty (pronounced: ming). Explore the history or the Ming dynasty. Here is a link to a short video summary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AtHGNZs6Urs

- Explore other Chinese treasures that have gone missing. Here is a link to the missing treasures of the summer palace: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-12/01/c_139556267.htm

- Aunt Lin was sent away to the countryside to work on a farm during the Cultural Revolution. Learn more about the Cultural Revolution at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7G0UXnXpABw and/or read Little White Duck, a graphic novel by Na Liu.

Math Suggestions

- Map the travels of Mia and Jake as they search for the treasure. Calculate the total distance they traveled. Order their trips from shortest to longest and calculate the average distance traveled for each journey.

- Plan a trip to Fuzhou. Calculate the cost of airfare, hotels, and transportation. Here is a website with information about Fuzhou: http://www.chinatouristmaps.com/city/fuzhou.html

- Use tangrams to create representations of the historical sites mentioned in the story. Here is a link to a digital tangram builder: https://mathigon.org/tangram

Art and Architecture Suggestions

- Create a pen and ink drawing similar to the crane picture described in chapter 1.

- Examine the architecture of the historical sites visited in the story.

- Create original drawings of the historical sites visited in the story.

- Mia and Jake see many Buddha statues at the Yongquan Temple. Examine images of Buddha statues from China, noting the variations in scale and the variety of materials used to create the statues. You could do the same with Guanyin Pusa, whose statue Mia and Jake also see at the temple.

Science Suggestions

- Compare Fuzhou’s climate to the climate where you live. How is it the same or different?

- How do the geological features in Fuzhou compare to those near your home?

Themes

Family

Family is an important theme in The Emperor’s Riddle. Mia travels to Fuzhou, the family’s ancestral home, with her mother, aunt, and brother. They stay with her uncle, who is living in the apartment that belonged to his parents, Mia’s grandparents. Mia feels inferior to her older brother. She has a close bond with her aunt, but Mia feels as if Mia’s mother lives in a different world. Events that unfold in the novel provide opportunities for Mia to grow closer to her mother and feel more equal to her brother. Her uncle is a stranger to her at the beginning of the story, but their relationship also grows over time.

Coming of Age

Mia is the younger of the two children in her family. She is a daydreamer who has trouble focusing in school. Her brother, Jake, is a charismatic athlete who does well in school. Mia is close to Aunt Lin, her Mom’s older sister, but she has a hard time connecting with her mother. When Aunt Lin goes missing, Mia loses the person on whom she relies for advice. As Mia and Jake team up to find Aunt Lin and the treasure, Mia must rely on herself to make decisions. Jake is impressed by Mia’s vast knowledge of history, and both realize that this is a valuable asset in their search. In the end, it is Mia who saves the day in a hand-to-hand fight.

Heritage

Mia has always known that Fuzhou is her family’s ancestral home. She visited once when she was very young, and now, at eleven, she is making her second family trip to Fuzhou. She has loved hearing Aunt Lin’s stories about Emperor Zhu Yunwen, yet she is a reluctant traveler to China. Mia misses her friends back home. After looking through a trunk of family memorabilia, Mia begins to develop more of a connection to her heritage and a sense of belonging. One of the items in the trunk is a crane painting once owned by an ancestor who knew Zhu Yunwen. The treasure map and clues are discovered on the back of the painting, setting the events of the story in motion.

Tropes

The story’s antagonist, Ying, is described in chapter 2 as a typical bad guy. He is unsmiling and powerful, “with fists as solid as oak.” Ying’s brow is often furrowed, his eyes are heavy lidded, and his hair is like a black cloud above his face. On page 22, “He slipped away like a shadow leaves a sunny room.”

Study Guide

Back of Book Summary (author’s website): http://katzhangwriter.com/index.php/the-emperors-riddle/

Mia Chen is on what her mother calls a Grand Adventure. She’s not sure what to make of this family trip to China and didn’t want to leave her friends for the summer, but she’s excited about the prospect of exploring with her Aunt Lin, the only adult who truly understands her.

Then Aunt Lin disappears, right after her old nemesis, a man named Ying, comes to visit. Mia knows that, years ago, when Aunt Lin and Ying were sent to the Fuzhou countryside to work as laborers, the two searched for an ancient treasure together—one that still hasn’t been found. She’s suspicious that their shared history might be linked to Aunt Lin’s disappearance.

When Mia discovers an old map filled with riddles in Aunt Lin’s room, she quickly pieces together her mission: find the treasure, find her aunt. Now, Mia, along with her big brother, Jake, must solve the clues to rescue the person she knows best in the world—and maybe unearth a treasure greater than her wildest dreams.

Character Analysis

Mia Chen: Mia is an eleven-year-old girl from Memphis, Tennessee. Early in the story, she describes herself as a “puzzle piece that doesn’t fit” (p. 2). She feels overshadowed by her high-achieving older brother, Jake. Mia is a reluctant participant in her family’s summer trip to her mother’s childhood home in Fuzhou, China. Mia’s relationship with her mother is less than ideal, but she has a strong bond with Aunt Lin. She feels they both “love stories, history, and make-believe” (p. 6). Mia often daydreams and has a hard time paying attention in school.

Mom: Mom is a busy single mother raising two children. She frequently relies on Aunt Lin for childcare. Mom is described as “always punctual” and “never letting her thoughts wander” (p. 5). Mia’s father left the family when the children were young.

Aunt Lin: Aunt Lin is Mom’s older sister. She seems to understand Mia in a way that Mia’s mother doesn’t. Aunt Lin came of age during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and spent three years working in the countryside in Fujian province before being able to go to university. During her time in Fujian, she learned of a legendary treasure hidden by emperor Zhu Yunwen over 600 years ago.

Jake: Jake is Mia’s older brother. He is described as charismatic and athletic, someone who “does well in school without even trying” (p. 6).

Uncle: Uncle is Mom’s older brother. His appearance is described as a “laughing Buddha statue come to life” (p. 13). Mia met Uncle only once before, when she was very young. He is a stranger to Mia, and through no fault of Uncle, she has a hard time connecting with him.

Ying: A large man described as “powerfully built” with “fists as solid as oak” (p. 13). He met Lin when they worked on the same farm during the Cultural Revolution. They were once close friends who dreamed of finding Zhu Yunwen’s hidden treasure. They parted on bad terms because Ying wanted to profit from finding the treasure. Ying’s wife is very ill.

Thea and Lizbeth: These are Mia’s best friends from Tennessee. Mia misses them, and they often figure in her memories.

Zhu Yunwen: Zhu Yunwen is also known as Jianwen. He became the second Ming emperor when he succeeded his grandfather to the throne in 1398. He disappeared in 1402. Many believe he died, while others are convinced he went into hiding, dreaming of the day he might one day regain power. The Emperor’s Riddle storyline proposes that Zhu Yunwen hid a treasure from his imperial riches before going into hiding.

Vocabulary List

Chapter 1: swathed (p. 7)

Chapter 2: nebulous (p. 13), dour (p. 15), mollified (p. 19)

Chapter 3: ponderous (p. 26), harried (p. 27)

Chapter 5: lattice (p. 42) balustrade (p. 42)

Chapter 6: tangible (p. 50)

Chapter 7: impetuous (p. 61)

Chapter 10: loitered (p. 80)

Chapter 11: facade (p. 99), fretwork (p. 99), anachronism (p. 101)

Chapter 12: scabbard (p. 104)

Chapter 13: wended (p. 109)

Chapter 15: furrowed (p. 131)

Chapter 17: rankled (p. 150)

Chapter 19: exasperated (p. 167)

Chapter 20: perfunctory (p. 179), eclectic (p. 180), dais (p. 184), niche (p. 184)

Chapter 21: stoic (p. 197)

Chapter 22: lithe (p. 202)

Chapter 24: threshold (p. 211)

Chapter 25: befuddled (p. 220)

Riddles (in the order in which they were solved)

#1

At the foot of the mountains

Sweet water flows, singing

Not only in the rivers

But pulled from the earth.

Seek me at the edge of the ring.

#2

Jutting above the world on nine glazed layers

One thousand buddha chant in unison.

Their voices are backed by the peal of heavenly bells.

#3

They came from the seas, murdering and pillaging

Twenty thousand strong, like a battering wave

But like a wave, they retreated again

Driven by the sword of war’s minister.

Find me in the southern heart of this lionheart’s hearth.

#4

Two brothers stand, eye to eye

The fairer steady on the turtle’s back

Search for me low, on the heads of the darker brother’s feet,

Carved into a cheek like a scar

#5

I lie cloistered in a shadowy mountain glen

Edged by sea, enclosed by sturdy walls of stone

But protection of my eternal sleep

Lies with the twin dragons stretched out below

Approach me at my final rest

And look for me at the head.

Author: Karen Gaul, Grade 5 Teacher, Winchester Thurston School, Pittsburgh, PA

2024