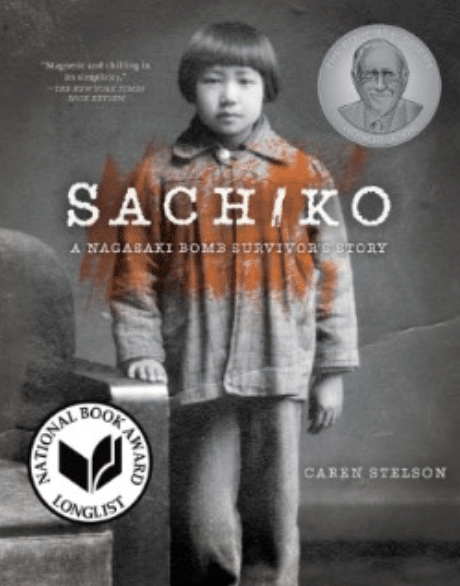

Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story

- Non-fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: war, survival, grief, resilience

This biography told to Caren Stelson of Sachiko Yasui, who was a six-year old in Nagasaki when atomic bomb fell on her hometown on August 9, 1945. Unlike Sadako, the young girl who died from the bombing in Hiroshima and with whom students are familiar from the Peace Statue and the 1000 cranes, Sachiko Yasui has survived the effects of the bombing into adulthood and is able to relate the story of her life and work for peace. With historical narrative interwoven in a survivor’s prsonal story, the complex historical events leading up to, during and post war become real to a teenager who may consider World War II ancient history. Relevant in our world today where nuclear issues, power politics and nuclear possession still dominate the news/our world, the story also represents how an affected country has turned to ‘peace education’ with the mantra to the world,” never again.”

In 2005, Sachiko Yasui and Caren Stelson met in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Sachiko was a survivor of the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and Caren was the daughter of a World War II veteran. Within five years, the two decided to collaborate on writing Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story. Clearly, both women strongly believed that this story needed to be told.

When the bomb hit on August 9, 1945, Sachiko was playing outside with her friends and her younger brother. She was the only survivor—the rest died instantly. Over the next sixteen years, nearly all of Sachiko’s family members died from the effects of radiation sickness, including four of her siblings and her father.

The story is immensely compelling. Sachiko’s experiences provide an up-close, personal view of the atomic bombing. Temperatures following the detonation reached as high as 4,000 degrees Celsius. Thirty-six percent of the city was destroyed, including nearly everything near the hypocenter. Damage extended out as far as 2.5 miles. As many as 74,000 were killed in Nagasaki and roughly 125,000 in Hiroshima. An additional 650,000 survived with physical and emotional scars that lasted a lifetime. For most students, such numbers are beyond comprehension. Sachiko’s story, however, is imminently relatable.

In addition to the story of Sachiko, the book contains numerous sidebar articles providing helpful historical context. Each sidebar is approximately two pages and together they cover ten topics (World War II, Racism and War, The Potsdam Declaration, Little Boy and Fat Man, Radiation Sickness, the U.S. Occupation, the Cold War, the Long-term Effects of Radiation, the Hydrogen Bomb, and the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Nuclear Bombing). Each can be read independently of Sachiko’s narrative, but together they provide a powerful story. The book is also filled with photographs that add important detail and richness, many of which are candid snapshots of Sachiko and her family members.

Though the bombing of Nagasaki lies at the center of the book, most of the text focuses on the years following the war. It is particularly helpful in highlighting the lingering after-effects of the war, including the ongoing financial and health struggles of Sachiko’s family, the orphans who wandered the streets for years, survivor’s guilt, post-traumatic stress disorder, and the ongoing implications of the Cold War for the Japanese. Sachiko and Caren also situate the story within world history, and significant sections of the book focus on such events as the Korean War, the 1963 African American protests in Birmingham, and the Smithsonian controversy regarding the Enola Gay.

All of these topics are deployed to remind readers “never again.” Clearly Sachiko wanted her readers to internalize the horrors of war and take active steps to promote peace. Within the text, Sachiko highlights the work of peace activists Mohandas Gandhi, Helen Keller, and Martin Luther King. Each of the three served as a role model for her as she struggled to make sense of the violence within her own life.

When using Sachiko in the classroom, several possible topics/lessons emerge. One is the role of racism in perpetuating violence. Besides the extended sidebar on the role of racism in World War II, Caren and Sachiko also make explicit comparisons with racism in the U.S., including a look at the 1960s civil rights movement. Teachers could make connections to numerous contemporary events that students may or may not fully understand. The George Floyd murder and subsequent protests of the Black Lives Matter movement during the pandemic, the heated fights surrounding illegal immigration, or even the murder and expulsion of the Rohingya in Myanmar could make interesting comparisons when discussing the overlap between racism and violence.

Another recurring theme in the text revolves around individual responsibility and finding one’s voice. After the bombing, the survivors (who were referred to as hibakusha) (pronounced: he-BAH-KU-shah) were shunned by many within Japanese society. Sharing her experiences in school, Sachiko explains that, “Bullies hurled out words such as baldy, monster or, worse, tempura—referring to the Japanese style of deep-fried vegetables, fish, and other food” (61). Because of such intense discrimination, for most of her life Sachiko preferred not to talk about the bombing to avoid drawing attention to herself and shame to her family. And yet, the book is also a detailed account of Sachiko’s coming to terms with the trauma and accepting the responsibility to share her story with the world.

When Sachiko is teased by classmates, her mother encourages her to write the story of her life and share it with her teacher. When Helen Keller visits Nagasaki in 1948, Sachiko is amazed when Keller steps up to the microphone, “cleared her throat and spoke to the thousands before her in a breathy voice, slowly, without changing pitch, sometimes garbled, but with great determination” (76).

Diagnosed with cancer, in 1961 surgeons remove Sachiko’s thyroid. The procedure left Sachiko unable to speak for months. “Who am I without a voice?” Sachiko asked herself. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, Sachiko reflected on his message of peace when he said, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter” (101). Finally, during the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing, Sachiko summoned up the courage to tell her story publicly when she addressed an audience of sixth-grade children. Since then, she has shared her story with thousands of individuals through lectures, interviews, and broadcasts.

Within the classroom, teachers could invite their students to think about their own responsibility for speaking out against violence, injustice, and discrimination. They might consider having their students write a letter about an important issue and send it to an elected official. They could discuss everyone’s responsibility to speak out in the hallways, schoolyards, and even on social media when they witness bullying, racism, or physical violence. Every student has a voice, though we may be hesitant at times to use it.

There are many other pedagogically useful themes highlighted in Sachiko ranging from individual fate to survivor’s guilt to post-traumatic stress disorder. In short, the possibilities for classroom engagement and instruction are limitless. Many students may already be familiar with Sachiko’s story if they read the companion volume A Bowl Full of Peace, also written by Caren Stelson for elementary school readers. By making comparisons with their own life experiences, teachers will find that Sachiko can be a powerful teaching tool to help students understand the nuclear attack on Nagasaki and its relationship to our current world still plagued by violence.

Author: David Kenley, PhD, Dean of the College or Arts and Sciences, Dakota State University

2023

NCTA webinar with author Caren Stelson

A Minnesota Book Award Finalist

A Robert F. Sibert Informational Honor Book

Longlisted for the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature