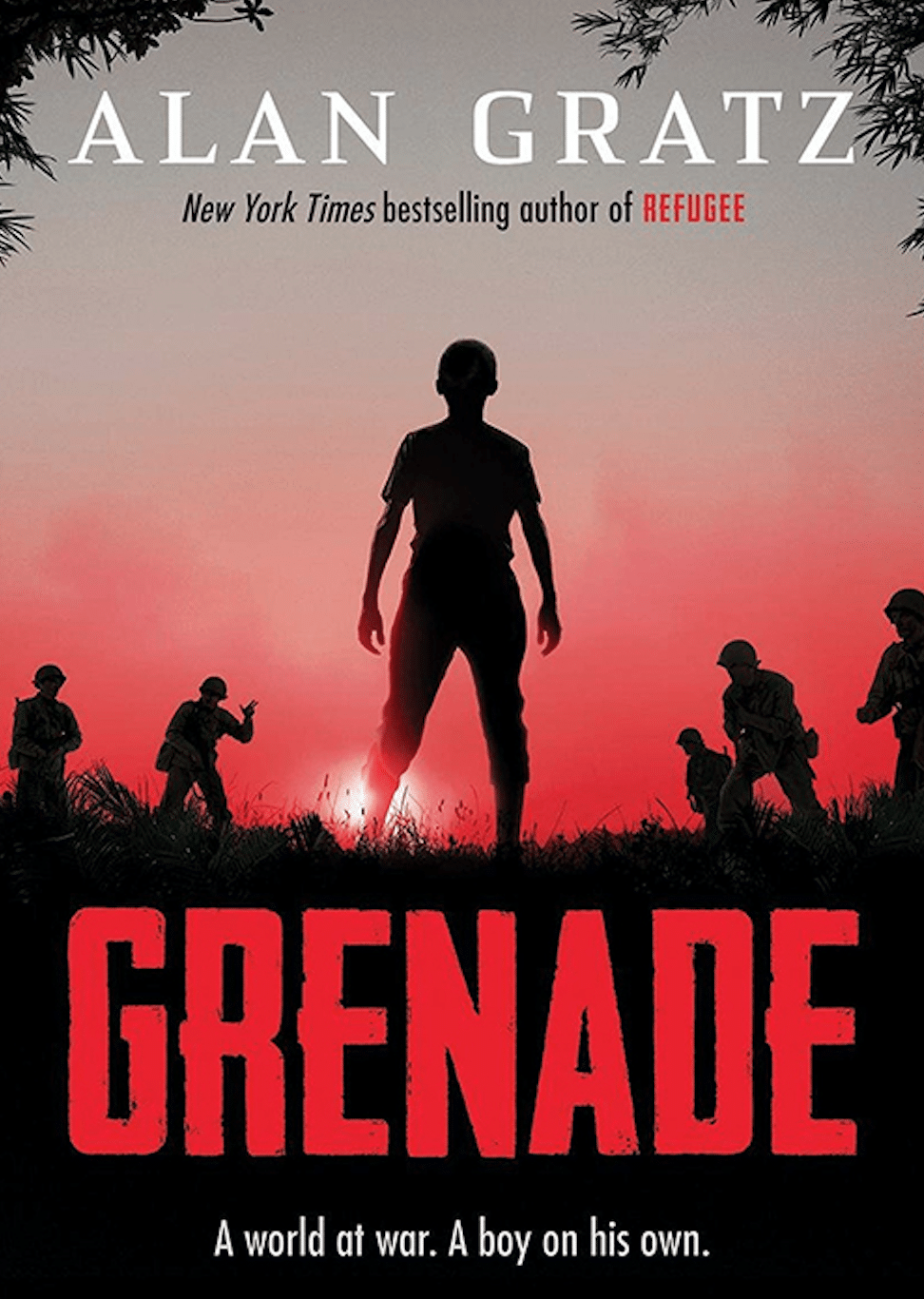

Grenade

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: war, death, adventure, coming-of-age, empathy

It’s 1945, and the world is in the grip of war.

Hideki lives on Okinawa, an island near Japan. When he is drafted to fight for the Japanese army, he is handed a grenade and told: Don’t come back until you’ve killed an American soldier.

Ray, a young American Marine, has just landed on Okinawa. This is Ray’s first-ever battle, and all he knows is that the enemy is everywhere.

Hideki and Ray each fight their way across the island, surviving heart-pounding clashes and dangerous attacks. But when the two of them collide in the middle of the battle, the choices they make in that single instant will change everything.

Alan Gratz’s Grenade is a novel about an Okinawan boy named Hideki who encounters an American G.I. named Ray during the Battle of Okinawa, a decisive battle between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Allied Forces led by the United States. The battle started on April 1, 1945, and lasted a grueling 83 days. At the conclusion on June 23, the Allied Forces (consisting mostly of American Marines) gained complete control of the main island, enabling them to stage the next planned phase of the war—that is, attacking mainland Japan. But on August 15, after the dropping of the atomic bombs on August 6 (Hiroshima) and August 9 (Nagasaki), Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces, ending the war in the Pacific.

Okinawa continued to play a role in the geopolitics of the region after the war. The United States occupied Okinawa and built many military facilities there and throughout mainland Japan. Some of these bases played an important role in supporting American military operations during the Korean War (1950–1953). A security treaty between the U.S. and Japan was signed in 1951 that allowed American bases to be established in Japan. A few years later, this was replaced by a more comprehensive military pact between the countries (United States–Japan Security Treaty, known as Anpo, signed in 1960). There were massive public demonstrations in Japan against this treaty in 1959–1960 and again in 1970. During the Vietnam War, Okinawan bases were used to support and supply the American troops deployed there.

President Nixon ceded control of the islands to the Japanese in 1972, returning Okinawa to Japan with its full prefecture status, but large U.S. military bases remain. About 54,000 American servicemen are posted in Japan today, and as many as 30,000 of them are in Okinawa, representing the largest concentration of American troops anywhere in the world.

The presence of American bases in Okinawa has caused a great deal of tension between the U.S. and Okinawan governments, stemming from residents’ complaints about noise, land use, and crime, not to mention general concerns around hosting American troops. The Japanese government will not abrogate the treaty for security reasons, but promises were made to work harder with the U.S. to manage these issues.

Historically, Okinawa was the center of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, which had its own distinct culture and language. The kingdom was colonized by the Japanese in 1609, when the Satsuma domain in southern Kyushu invaded the kingdom, dethroning King Shōnei. In 1879, Okinawa was officially incorporated as a prefecture into the nation of Japan.

The setting of the story

During the last phase of World War II, Okinawans were forced to defend Japan, even though they had been treated as second-class citizens under Japanese rule. At the end of the war, Okinawa was placed under American military rule, and in May 1972, it was returned to Japan. As a result of this 400-year history of foreign occupation, many Okinawans still feel a great deal of resentment toward both the Japanese and the Americans.

Draft-age Okinawan males, as citizens of Japan, were required to join the military during World War II. Toward the end of the war, Japan did not have enough soldiers, and so high school, college, and university students were mobilized (gakuto dooin) to help with the war effort. Many were sent to work in factories. Female secondary school students were assigned to non-combatant roles like nursing, and male students took on paramilitary activities. In Okinawa, about 1,500 male and 500 female students were mobilized. Hideki and Kimiko in Grenade are two high school students who were enrolled in the student mobilization troops.

In Grenade, civilians are described as throwing themselves off a cliff instead of being captured alive by the American troops. This kind of suicide was not reported at then Battle of Okinawa, though it likely happened. In the year prior, Okinawan soldiers and civilians did choose to jump off cliffs to their deaths in the Saipan Islands (Banzai Cliff) and at Suicide Cliff rather than fall into enemy hands. The exaggerated description in this story may have value as a novelistic device, but it will perpetuate the stereotype that Japanese people simply did what they were told during the war.

The young Hideki is portrayed sympathetically. He has not experienced a lot in life, much less on the battlefield in which he was unwillingly inserted. Hideki is contrasted to Japanese soldiers from the mainland, who are represented as unfeeling, interested only in following orders. They do not exhibit human decency, and don’t hesitate to take the lives of other Japanese. In contrast to this portrayal, American Marines, especially one of the main characters, Ray, are benevolent, compassionate, and morally righteous. Ray is an innocent young adult from a farming family in Iowa, who, like Hideki, doesn’t know much about war, much less what it is like to participate in one.

There is a three-way tension among the American military, the Japanese Imperial Army soldiers, and Okinawan civilians caught between them. Because this is a work of fiction, a teacher should not judge Grenade for its historical accuracy. Nevertheless, it is important to note the rather one-dimensional characterization of the Japanese Imperial Army as savages and the American troops as bringers of peace and mortality.

Author: Hiroshi Nara, emeritus professor, University of Pittsburgh

2025

1. Summary

The novel Grenade starts on April 1, 1945, the same day that the Battle of Okinawa began in the Pacific Theater toward the end of World War II (1941–1945). In the first two chapters, we are introduced to Hideki Kaneshiro, a teenage boy living on the Japanese island of Okinawa, and Ray Majors, an American soldier. The chapters alternate between the viewpoints of these two characters, offering us the Okinawan and American perspectives from opposite sides of the battlefield. The loyalties of both Hideki and Ray are tested as the narrative plays out.

2. Analysis

Grenade works well as a middle school novel with any grade 6–8 curriculum that includes material about World War II in the Pacific Theater, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The chapters are accessible, written in a manner that helps students to understand the motivations that propel the main characters. Grenade also provides broader context, offering perspectives on cultural mores, geopolitical fractures, and the rise of militarism.

Hideki and Ray are described as typical soldiers: they are putting their lives on the line in response to ideologies and political circumstances. These powerful themes—the brutality and amoral nature of warfare, the propaganda and nationalism at the heart of wartime tensions, and the search for humanity at the core of both main characters—challenge the reader to think deeply about the Battle of Okinawa, a historical event that is increasingly abstract to students today.

3. Cultural & Historical Themes

Any educator using this text in their class has an opportunity to delve deeper into the history of World War II in the Pacific Theater. Teachers who use this book could talk about Hideki as an Okinawan and discuss the values instilled in him by the Empire of Japan, which towards the end of the war used the warrior code of bushido (bushidō) to propel young men into battle without adequate training.

4. Historical Relevance & Reflection: Current Event Connections

Although Grenade is a middle grade text, it can be used in tandem with current events lessons, specifically within a social studies or history classroom. Its subject matter is tied to historical moments associated with World War II: trade disputes, diplomatic conflicts, the rise of totalitarian and fascist regimes, and wars against neighboring countries. If a teacher is inclined to connect Grenade to current events, then students could discuss real-world corollaries in the twenty-first century, such as the rise of totalitarian regimes in Hungary and Turkey, the Russo–Ukrainian War, and the growth of extreme right-wing politics around the world. The personal trials and tribulations suffered by the characters Hideki and Ray could be seen in historical perspective, and students might come to understand how the same forces may be at play for soldiers facing similar circumstances today.

5. Appropriate Grade Levels

The appropriate grade levels for Grenade is middle school readers in grade 6–8. Given the issues with reading levels among middle and high schoolers, it may also be appropriate for readers in grade 9 as well. However, if teachers plan for enough in-class reading days, chunk the text appropriately, use reading group strategies alongside audio versions of the text for students who need accommodations, and budget time to check for understanding, then the text should work for a majority of middle school learners.

6. Activities

a. Reading & Discussion: If enough in-class reading time is scheduled, the teacher(s) can have meaningful Socratic roundtable discussions with students, as a class or by creating groups of students. These can serve as reflective pauses in the allotted reading time or can be used to assess how students have grasped concepts and events within the text, to determine if they have used the necessary critical reading and thinking skills they are being encouraged to develop.

b. Group Project Presentations & Reports: Students can be divided into pairs and assigned a particular concept or idea associated with This could be the Battle of Okinawa itself, or other historical aspects of the text that students can learn more about through research and writing. Topics can range from the Japanese warrior code (bushidō) that influenced Hideki, to the history of the Okinawan Islands, to the American regiments that were ordered to invade Japan. Students could write brief research papers, create slide deck presentations, or do these activities in tandem.

c. Primary Source Reading with Flowcharts: Students can be given a flowchart to use in tandem with primary sources while reading Grenade. Sources might include documentary footage, testimonials from people in Okinawa who were directly affected by the war, or testimonials from American soldiers who took part in the invasion. Primary sources can be used to paint a fuller picture of the Battle of Okinawa. The Pacific Theater can be explored from both sides of the conflict, drawing on civilian and military sources to paint a full picture. The flowchart will help students to group information from primary sources with textual evidence and analysis.

d. Cultural Immersion Activities: Consider cultural immersion activities to help students better understand the humanity and personal motivations of characters such as Hideki. Because Hideki is steeped in Okinawan and Japanese culture, teachers can find photos to show students, or even cultural artifacts that Hideki might have used on a daily basis in early twentieth-century Japan. These could range from Japanese chopsticks and rice bowl to a koi fish flag, a samurai sword, or an example of a Japanese school uniform worn during World War II. Providing a kinesthetic class activity where students can learn how Hideki would have lived his day-to-day life will help to reinforce overarching themes at the heart of Grenade.

7. Common Core Standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.2

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.5

Describe how a text presents information (e.g., sequentially, comparatively, causally).

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.8

Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.9

Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-8.10

By the end of grade 8, read and comprehend history/social studies texts in the grades 6–8 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.8.1

Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.8.2

Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.8.3

Analyze how particular lines of dialogue or incidents in a story or drama propel the action, reveal aspects of a character, or provoke a decision.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.8.10

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, at the high end of grades 6–8 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

8. Literature & Media Connections

a. Middle School Text: Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes by Eleanor Coerr

A text that mainly deals with the aftereffects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Coerr’s novel about Sadako and her ordeal can serve as a final reading for a whole unit or semester about the Pacific Theater of World War II and the impact of defeat on the Japanese people, who paid the price for the political and military mistakes of their leaders.

b. High School Text: Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths by Shigeru Mizuki

If Grenade is read in the grade 9 classroom, Mizuki’s manga novel would provide a nice supplement. Ray Majors shows us the perspective of the American forces but Hideki Kaneshiro offers a civilian perspective. By reading Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, students could learn what it was like in the Japanese military and what the Japanese thought of the efforts of their military leaders.

c. Film Connection: Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, both directed by Clint Eastwood

While these films would be more suited to a high school classroom, they provide valuable visual addendums and even more historical realism to the types of conflicts that Grenade introduces. Showing these films is up to the discretion of the teacher—it may be wise to use only specific scenes to make points about the larger conflict or specific passages of the text.

For further historical and cultural information, please refer to the Culture Notes for Grenade by Prof. Hiroshi Nara on the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia website.

Author: Matthew Kizior, M.Ed.

2025

Fill-out the online form to access the NCTA archived webinar with the author Alan Gratz