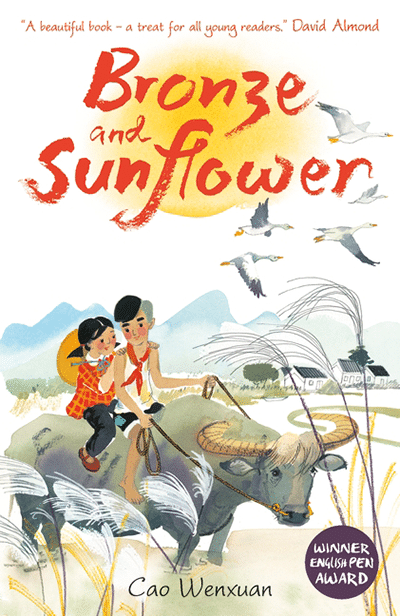

Bronze and Sunflower

- Fiction

- Set in China

Keywords: translation, family, disability, friendship, loyalty

Cao Wenxuan, author of Bronze and Sunflower, is one of China’s most esteemed and best-selling children’s book writers and has won several of China’s important awards for children’s literature. A professor of Chinese literature at Peking University, Cao Wenxuan has seen many of his books become bestsellers in China, and his work has been translated into French, Russian, Japanese, and Korean. Bronze and Sunflower is his first full-length book to be translated into and published in English. First published in England in 2016, it was the recipient of the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award. Published in the U.S. in 2017, it is now the winner of the Freeman Book Award for Young Adult/Middle School literature on East Asia.

Sunflower is an only child; when her father, an established artist from the city, is sent to the rural Cadre School for political “re-education” she has to go with him. Her father finds his new life of physical labor and endless meetings exhausting. Sunflower is lonely and longs to play with the local children in the village across the river. Bronze, a local boy from the village that she sees riding his water buffalo, is also an only child too and hasn’t spoken a word since he was traumatized by a terrible fire. Bronze and Sunflower become inseparable, understanding each other as only the closest friends can. Translated from Mandarin, the story meanders gracefully through the challenges that face the family, creating a timeless story of the trials of poverty, hardship, rural-urban divisions, the Confucian values of family and service to the society, and the power of love and loyalty to overcome hardship.

Author: Cao Wenxuan (pronounced: “Tsao Wen-shwan”; Cao is his family name, and Wenxuan is his personal name) was born in the village of Longgang 龙港村 near the town of Yancheng 盐城, in Jiangsu province 江苏, in central east China in 1954. His father was a school principal. Cao Wenxuan is now a professor of literature at Beijing University, where he studied literature. He says the idea for the story of Bronze and Sunflower came from a friend whose family had been sent to the countryside during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). During this turbulent time in Chinese history, schools were closed, including Cao’s, and he traveled throughout the countryside as part of the Dachuanlian 大串联 (big exchange; pronounced: “dah-CHWAN-lee-ehn”), a movement in which young activists were encouraged to spread the message of the Communist revolution. He was only twelve or thirteen at the time.

Geography: Jiangsu province is just north of the major financial city of Shanghai and is bordered by the Yellow Sea on its east. Its capital is Nanjing, and the province also includes the major cities of Suzhou and Wuxi. Famous for its salt marshes and wetlands, Jiangsu is flat, with plains covering 68 percent of its total area. Water covers another 18 percent, including many major rivers (the Yangtze, the Huai, the Yellow River, and the Grand Canal) and lakes (Lake Tai, Lake Hongze, Lake Gaoyou, Lake Luoma, and Lake Yangcheng). The novel is set in the wetlands of northern Jiangsu province.

Setting: The novel takes place in the late 1960s and early 1970s, during the Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution had roots in the Great Leap Forward (1958–1961), the collectivization of agriculture and industry that precipitated a famine that left as many as forty-five million dead. Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China and chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was blamed for his extremism and was partly sidelined by Communist Party leaders, who pulled back some of the most extreme collectivization efforts. Mao tried to reassert control by setting radicalized young people against the Communist Party hierarchy and what he called the “Four Olds”: Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas. While the Great Leap Forward was considered a restructuring along socialist lines of the rural areas, the Cultural Revolution was an attempt by Mao to reform urban culture and institutions and ultimately regain control of political power. When the violence in attacking the “Four Olds” in the cities became too disruptive, the urban radicalized young people were sent (sometimes voluntarily and sometimes coerced) to the countryside to “learn from the peasants.” They were known as “sent-down youth.”

At the same time, Mao attacked the urban political elite, called “cadres,” more directly. The term “cadre” (ganbu) refers to any public official in China. In 1968, the May Seventh Cadre Schools were started, in accordance with Mao Zedong’s May Seventh Directive, released to the public on May 7, 1966. In this directive, Mao suggested setting up farms, later called cadre schools, where cadres “sent down” from the cities would perform manual labor and undergo ideological re-education. Cadres would take turns going to the rural villages to gain first-hand experience in productive work, an idea called “education through labor.” Most of the cadres had grown up in the cities and knew very little about life in rural areas or farm work. Children might be left with grandparents in the cities or go with their parents to the country. In addition to work in the fields, the “sent-down cadre” spent much of their time in long “re-education” meetings to rid themselves of “Old Ideas” and “Old Habits.” Artists, like Sunflower’s father, were considered cadre and were usually restricted to producing government propaganda posters.

Authenticity and Historical Specificity Issues: Cao Wenxuan had a deep knowledge of the rural area of Jiangsu province and its country people, and the book reflects their conditions with accuracy and empathy. Life in China, though, has changed dramatically since the Cultural Revolution. The rate of urbanization has increased, and 55 percent of China’s population are now urban dwellers. While rural populations still suffer from natural disasters such as locusts and flooding, their standard of living has improved dramatically. Schooling has become more expensive, though. Special education for students with special needs, like Bronze, is still underdeveloped, and there are differences in quality between rural and urban schools.

Resources and Additional Background Material:

http://www.theclassroombookshelf.com/2017/05/bronze-and-sunflower/

https://www.britannica.com/place/China/Social-changes#ref590802

Author: Karen Kane, Columbia University, National Consortium for Teaching About Asia (NCTA)

November 2020

Overview

Originally published in Chinese in 2005

Genre: Historical fiction, Cultural Revolution

Pages: 381. Lexile: 790L Reading Level: 5.6

About the Title

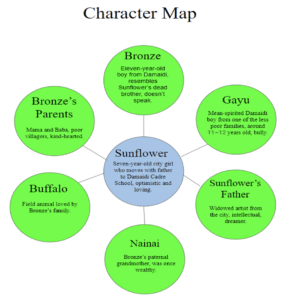

The title, Bronze and Sunflower, reflects the names of the two main characters. The author has used a third-person omniscient point of view, with the story alternating between the perspectives of the title characters.

About the Author

Cao Wenxuan (pronounced: Tsao Wen-shwen) is a Chinese author born in 1954. Cao is his family name, and Wenxuan is his given name. He grew up in rural China during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). His father was the principal at a rural school, and the family lived in poverty. Cao Wenxuan is a professor of literature at Beijing University. His novels are well-loved in China.

About the Translator

Bronze and Sunflower was translated by Helen Wang. Wang lives in London and is the curator of East Asian Money at the British Museum. Her translation of Bronze and Sunflower won the 2016 Marsh Award for Translated Children’s Literature. Wang has also translated short stories and essays from Chinese to English along with other novels for children and young adults.

Recommended Audience

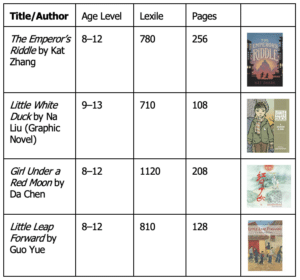

Some of Cao Wenxuan’s writing has been described as melancholy, and this is certainly true for Bronze and Sunflower. The story is beautifully told, but this book will not appeal to all students. Specifically, its slow pace may be a barrier to reluctant readers; it is recommended for readers aged 9–13. Bronze and Sunflower could also be considered for readers over the age of 13, particularly older readers who might struggle with more complex texts. The merits of Bronze and Sunflower lie not only in its poignant storytelling, but also in its rich sharing of cultural information.

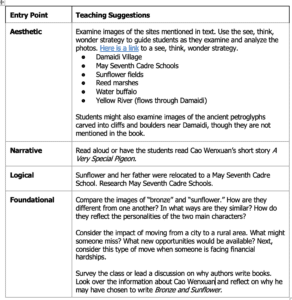

Curricular Entry Points

Specific Teaching Suggestions

Reading Suggestions

- Read Aloud or Whole Class Assigned Reading: While Bronze and Sunflower can be read aloud or assigned to a whole class as independent reading solely for its literary merits, it is an ideal book to be integrated with a social studies unit on China or East Asia.

- Excerpt: Bronze and Sunflower is touching and compelling in many ways, but it may not be the type of fast-paced story many of our middle-year students are accustomed to. Consider working with pages 1–89 as a stand-alone short story.

- Small Group or Book Club Reading Choice: Bronze and Sunflower could be assigned as an enrichment activity for a small group of students. Similarly, it could be used for book clubs around the theme of Chinese culture. See below for suggested books that could be included in a Chinese culture–themed book club along with Bronze and Sunflower.

- Character Analysis: Compare and contrast the characters Bronze and Sunflower. Consider both internal and external characteristics.

Writing/Storytelling Suggestions

- Read the song lyrics in the supplemental materials aloud, and create stories to go along with them. Where possible, make connections to the characters in Bronze and Sunflower.

- Write a story in petroglyphs using the style of those found in the hills near Damaidi village.

- Write or tell an epilogue in which Bronze and Sunflower are reunited.

Social Studies Suggestions

- The story is set in Damaidi (pronounced: da-MAI-dee), a small village in Zhongwei. Find Damaidi on a map of China, noting that it is located in Ningxia, an autonomous region.

- Research the differences between a province and an autonomous region in China.

- The story takes place during the Cultural Revolution. Learn more about this period.

- Explore why the government set up the May Seventh Cadre Schools.

Math Suggestions

- Plan a trip to from Beijing to Damaidi. Calculate the cost of airfare, hotels, and transportation. Consider how a modern-day trip compares to how someone would have traveled fifty years ago, during the Cultural Revolution.

- Use tangrams to create representations of a sunflower, oxen, boat, and the village buildings mentioned in the story. Here is a link to a digital tangram builder: https://mathigon.org/tangram

Art and Architecture

- Sunflower’s father was an artist who worked in bronze.

- Make a model of the Damaidi village as it may have looked during the Cultural Revolution.

- Examine Cultural Revolution propaganda posters related to Cadre Schools. Here’s a link to a web page with posters: https://chineseposters.net/themes/may-seven-cadre-schools

- Petroglyphs can be found in the cliffs near Damaidi. Explore the history of petroglyphs and view images of those near Damaidi. Students might also create their own drawings in the style of the Damaidi petroglyphs.

- Draw a water buffalo, an egret, or other animals mentioned in the story.

Science

- Investigate the life cycle of the sunflower.

- Compare Damaidi’s climate to the climate where you live. How is it the same or different?

- How do the geological features of Damaidi compare to those near your home?

- Learn about Damaidi’s flora and fauna. Water buffalo, fish, egrets, and ducks are mentioned in the story, as are sunflowers, cogon grass, and arrowhead plants.

Themes

Family: As the story begins, Bronze’s family includes a grandmother, father, mother, and son. The family takes in Sunflower and treats her as one of their own. Family members are thoughtful and caring, often sacrificing for each other.

Loss: Sunflower’s mother and brother have both died. Not only have Sunflower and her father lost these family members, but they have also lost their home and way of life in Beijing. Tragically, Sunflower also loses her father.

Friendship: Bronze and Sunflower share a deep friendship despite being from different worlds. They spend hours together in the countryside. Even though Bronze does not speak, the two seem to understand each other.

Education: Education is not compulsory during this period in the Chinese countryside. Parents must pay to send children to school, and many do not attend. Bronze’s family is very poor, yet Sunflower’s education is of utmost importance. They regularly sacrifice to send Sunflower to school.

Hardship: Sunflower’s adopted family is very poor. They have trouble providing for even basic needs. Life in general is hard, and the villagers of Damaidi endure fire, locusts, flooding, and freezing temperatures.

Perseverance: Sunflower’s family never gives up in the face of hardship.

Sacrifice: Even though they are very poor, Sunflower’s adopted family makes many sacrifices to care for her and send her to school. The family makes the ultimate sacrifice at the end of the book, when they insist that Sunflower return to the city, where opportunities for a brighter future exist.

Nature: Nature is a powerful force in Bronze and Sunflower. Sunflower’s father drowns in the river. Winters can be very cold. Locusts destroy crops, and a wildfire threatens the village.

Symbols

Sunflowers: Sunflowers are symbols of happiness and optimism. The Sunflower character is an orphan who experiences loss, yet she is happy with Bronze’s family, despite living through many hardships.

Water: Rivers can be symbols of division. A river separates Damaidi village from the May Seventh Cadre School. The former urban dwellers now working at the Cadre School are separated from the rural villagers. These two classes of people live near each other, but crossing the river is not a simple endeavor.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials can be found on the following pages:

- Character map

- Songs

- Web links

Songs

Song learned from village girls (p. 116)

The rice cakes smell sweet,

Their scent fills the kitchen.

The leaves smell so sweet,

Their scent fills the house…

Song learned from Nainai (p. 113)

Little Sister we combed your hair

And now you look like a lady!

Big Sister Jeijei, we combed your hair

And now you look like a baby!

Nainai’s song while the women weave slippers (p. 119)

When roses bloom in the spring

And the silk worm season begins,

The women go out to pick mulberry leave

In pairs, in pairs

Their baskets hang from the mulberry trees

And they strip the branches bare in tears, in tears

Web Links

Blog: Randomly Reading: Book Review for Kids, Teens, and Grownups

Map: https://mapcarta.com/32622446

Interview with translator: https://worldkidlit.wordpress.com/2021/03/11/helen-wang-talks-to-nanette-mcguinness/

Author: Karen Gaul, Grade 5 Teacher, Winchester Thurston School, Pittsburgh, PA

2023

Teacher Vision Bronze and Sunflower Teaching Guide

Book review by Lisa See

Classroom Bookshelf teaching resource

Archived Book Group Bronze and Sunflower. (Once you have created a login for yourself at asiaforeducators.org, you are able to view and access all current and archived offerings from the main page. One (free) login suffices for all).

2016 Hans Christian Andersen Award