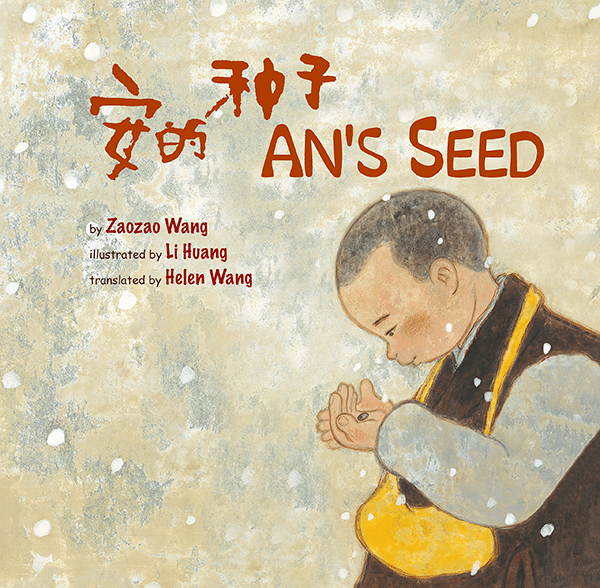

An’s Seed

- Fiction

- Set in China

Keywords: translation, bilingual, patience, mindfulness

A gentle fable about mindfulness, An’s Seed follows the actions of three young monks – Ben, Jing, and An – who are given the task of growing a lotus plant from a seed. One monk is too impetuous, one misguided, and one patient and wise. The illustrations have a simple charm befitting the story. The bilingual text may prove a bit awkward for non-Chinese readers, though. The central story is in Chinese; the English text is presented again at the end with smaller pictures. Nevertheless, its lesson on following the natural order and choosing thoughtful action is praiseworthy. A glossary of words and expressions is included for language learners.

An’s Seed is a picture book written by Zaozao Wang and illustrated by Li Huang. It tells the story of three young Buddhist monks—Ben, Jing (pronounced: Gihng), and An—each given a lotus seed by their master. The master tasks each of them with growing the seeds into full lotus flowers in the best way that they can. The novice monks go their separate ways, and each thinks about the best way to make their seed grow. A brief tale is then told of each little monk:

- Ben immediately goes to find a hoe and plants his seed in the snow-covered ground. He waits and waits for it to sprout, but nothing ever happens.

- Jing goes to find a flowerpot, soil, and a book that would teach him how to properly take care of the lotus seed. The seed starts to sprout, but to protect it, Jing puts a lid over the pot, which cuts off the oxygen and sunlight the plant needs to continue growing.

- Throughout the winter months, An does not plant the lotus seed given to him by his master. He focuses on the tasks at hand—going to market, sweeping, fetching water—until spring arrives. Then he plants his lotus seed in a pond, where it blossoms and thrives.

An’s Seed did not have to be set at a Buddhist temple or feature explicitly Buddhist characters, but the author is setting this story and its lessons within a particular cultural and philosophical paradigm. The story itself is a parable that could come right out of one of the most venerated Buddhist scriptures of all time, the Lotus Sutra. The imagery of the lotus seeds at the center of the story may even be offered as textual proof of this connection; however, the connection does not end there. Not only is An’s Seed a parable alluding to weightier philosophical texts that clearly influenced the author, but the book also offers lessons on particular Buddhist values as well. Given the book’s title, a reader might expect the main protagonist, An, to be the focus of the story. This is intentional, in that An displays two specific philosophical virtues that a Buddhist monk would be thinking about.

The first virtue is wuwei (pronounced: WOO-way), a concept translated as “non-action” that originated in Chinese Philosophical Daoism (formerly spelled Taoism and pronounced: DOW-ism) but was later absorbed by the Chan (pronounced: chahn) school of Buddhist thought as Buddhism took root in China. Wuwei is less about doing literally nothing and more about going with the natural flow of our circumstances and the world around us. This emphasizes that bending aspects of the world around us to our will is not always healthy or necessary, especially if we wish to be in harmony with the natural world. In this regard, it’s not surprising that most of the story does not focus on An’s actions. Ben’s and Jing’s actions take precedence to show their disregard for the philosophy of wuwei. They are more interested in quick results than acting in accordance with nature. An, however, understands wuwei intuitively, and he commits to plant his lotus seed in an environment where it will live and thrive. An’s everyday actions can be seen within the context of understanding the natural flow of events and the environment around him.

The second virtue is the Buddhist concept of upaya (“skillful means”; pronounced: ooh-PAH-yuh). Skillful means are usually interpreted as particular tools or ways of thinking that Buddhist practitioners can use in their meditation practice to mature further in a shorter amount of time. The author brilliantly turns this concept on its head through the actions of Ben and Jing: by relying on expediency, these two are the opposite of skillful. By rushing to grow their lotus seeds as quickly as possible, they doom themselves to failure. An wisely demonstrates skillful means by using his knowledge to provide a healthier environment for his lotus seeds. His patience in tending to the day-to-day activities of his temple is the best use of expediency in his practice; instead of rushing to plant his lotus seed, he uses every moment wisely.

Vocabulary Terms for An’s Seed

Four Noble Truths: Included in the first sermon the Buddha preached after achieving enlightenment, the Four Noble Truths express basic truths about existence in the material realm. These truths, which the Buddha discerned through his meditations, are as follows:

- All existence is dukkha (suffering; pronounced: DOOK-kuh).

- The cause of suffering is tanha (craving; pronounced: TAN-ha).

- The cessation of suffering comes from the cessation of craving.

- There is a path that leads out of suffering and that path is the Noble Eightfold Path.

Taken together, the Four Noble Truths sum up the human condition.

Eightfold Path: The Eightfold Path is the Buddha’s remedy for the suffering and craving that are at the heart of the ignorance he identified in his Four Noble Truths. Buddhists believe that anyone who follows the principles prescribed by the Eightfold Path will eventually work their way through their ignorance and achieve a greater realization of their inherently wise and compassionate nature:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

Karma: Karma (action; pronounced: car-mah) is the Buddhist doctrine by which samsara (rebirth or reincarnation; pronounced: sam-sahr-ah) is perpetuated in the life of an individual being. Karma refers to individuals undertaking mental or physical actions or states of being, either intentionally or unintentionally, that lead to a future consequence. An individual’s rebirth relies on the type of karma they have accumulated over the course of their previous life.

The Three Kinds of Practice

- Samadhi: Usually translated as “concentration,” samadhi (pronounced: suh-MAA-dee) refers to the ideal meditative state where a practitioner is not attached to ideas, thoughts, or concepts as they focus on their breath and are able to center their mind and emotions.

- Prajna: A Sanskrit word that translates as “best knowledge/knowing,” prajna is used to refer to the Buddhist concept of wisdom and usually refers to the type of wisdom a Buddhist practitioner attains after gaining insight through meditation. Prajna (pronounced: pu-RAH-ju-nah) is seen as intuitive, natural wisdom that someone starts to embody or realize after attaining a certain state in meditation.

- Sila: Referring specifically to precepts, sila (pronounced: SHEE-la) is the Buddhist practice of keeping and maintaining precepts to cultivate more wholesome states of mind and being. The precepts are seen as a way to give a Buddhist clearer direction in their life as either a monk or a layperson, given that they are training in virtue. According to the Vinaya Pitaka (literally, Basket of Discipline) of the Buddhist Pali Canon, there are 227 precepts for male monastics and 311 for female monastics.

Lotus Flower: One of the more iconic Buddhist symbols, the lotus flower represents many different aspects of Buddhist philosophy:

- The purity of the enlightened mind amid the suffering of samsara

- Nonattachment

- Spiritual growth and/or perfection

- The stages on the path of enlightenment

- Faith

Chan (Sanskrit: dhyana; Japanese: Zen): This is a state of calm attentiveness in which one’s actions are guided by intuition rather than by conscious effort. The term is known more widely throughout the world in its Japanese form, Zen.

Wuwei: An important Daoist concept that heavily influenced Chan Buddhism (known as Zen in Japan), the term roughly translates to mean “non-action.” To practice wuwei, a person might renounce all worldly possessions and power, and commit themselves to acting in accord with the natural world, interpreted as acting in accord with the universe, the Way—the Dao. Other Daoist philosophers and practitioners seek to act out wu-wei in society, meaning that they study and pursue spiritual practice in a way that will help their secular actions accord with “natural action” (meaning that they are not out of step with the Dao).

Author: Matthew Kizior, Career Readiness Teacher

2021

Appropriate Grade Levels: This book would be best used with 2nd and 3rd graders, to expose younger children to different cultures and languages. It could also be used to touch upon larger philosophical influences in a simple and straightforward way with 7th and 8th graders.

Activities that students could potentially engage in to further their understanding of this text include the following:

Discussion: Ask the students why An did what he did. What does this say about him as a character and what are the lessons of the book?

Creative project: Students are given the chance to make their own origami lotus flowers (or other flowers, depending on the skill set of the students). The teacher can then follow up with the students and ask them how they feel about their origami flowers and how they would make sure they were maintained and taken care of. The teacher can connect this to the lessons learned through the text. Here’s a link to one of the many videos on how to fold a lotus flower: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RiBpQS_6bG0

Vocabulary: If the teacher would like to focus on the use of Chinese vocabulary and have students learn these words and their associated meanings, students could engage in a mix-and-match vocabulary and drawing activity. Students can be split into groups, with each member of the group given a different word to learn and draw (either the object or action associated with that word). A simple mix-and-match activity could include romanized Chinese words, such as zhong zhi (seed) and fa ya (sprout/sprouting). Each student would study the meaning of their word, and once all students are finished studying and drawing, they can explain to the others in their group how to pronounce the word, what they drew, and what they learned in the process.

Common Core Standards

- ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.1. Ask and answer such questions as who, what, where, when, why, and howto demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

- ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.2. Recount stories, including fables and folktales from diverse cultures, and determine their central message, lesson, or moral.

- ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.1. Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

Literature and Media Connections

If this were a higher-level text, I would suggest connecting it to philosophical and historical texts that would illuminate the details of this story. However, for lower-level learners, I would suggest supplementing the use of this text with other children’s picture books that communicate similar value systems. The best and most easily accessible supplementary children’s books that also focus on Asian philosophy and Buddhist parables are written by Jon J. Muth. The three most approachable texts are Zen Shorts, Zen Socks, and Zen Ghosts. Each has adapted Zen Buddhist parables to fit within the lessons of the main character, the giant panda known as Stillwater. These texts can be used to deepen the understanding of what the students just learned through An’s Seed, with a teacher discussing how they share common themes.

One piece of visual media that could be used to grab students’ attention and provide a more vivid picture of the Buddha’s life story and values is the film Little Buddha (1994). Starring Keanu Reeves and Bridget Fonda, the movie tells the story of the Buddha alongside the story of children discovering that they are the rebirths of Buddhist masters. Through the movie, we find out how the children’s characteristics and their exciting journey align with the lessons the Buddha learned throughout his journey to enlightenment. The movie may work well with third graders, but it would probably work better with students in fifth grade and above. Teachers of different grade levels can meet to figure out how best to present information to the students over a series of years, reinforcing concepts that students would have first been exposed to in An’s Seed by watching Little Buddha later on in their school career.

Common Core Standards

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.W.2.2. Write informative/explanatory texts in which they introduce a topic, use facts and definitions to develop points, and provide a concluding statement or section.

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.W.2.7. Participate in shared research and writing projects (for example, read a number of books on a single topic to produce a report; record science observations).

Guidelines

How is this book in response/relation to previous literature?

This book is a quick summation and presentation of key Buddhist and East Asian philosophical values, as explained in the Culture Notes for this book. This is mainly a response to the religious and philosophical literature that has influenced certain communities for centuries. If a teacher is looking for a greater understanding of the concepts in this book, I recommend reading The Dhammapada and Tao Te Ching—key texts that are approachable and short.

How could the book address universal themes or common literary tropes?

An’s Seed, while addressing the specific themes mentioned in the Culture Notes, could show the student one of many ways a person can understand and express the values of compassion, wisdom, understanding, and appreciation of the natural world, particularly when paired with the Jon J. Muth books mentioned.

What curricular entry points would the book fit into?

This book would be a good use of literature to emphasize what may have been covered about Buddhism or Chinese philosophy in the course of discussing Buddhist or Chinese history and culture. It is also a good entry point for these topics.

Any specific suggestions for teachers using the book?

While it is satisfying to talk about compassion, wisdom, and understanding—which will inevitably be the relevant topics of discussion—it is also important to be clear about what is culturally relevant and philosophically significant when presenting this book within a certain context. Please see the Culture Notes for help in this regard.

Recommended Teaching Resources

Bertolucci, Bernado, dir. Little Buddha. 1994; Los Angeles: Miramax, 2004. DVD.

The Dhammapada. Translated by Valerie J. Roebuck. New York: Penguin Classics, 2010.

Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching. Translated by D.C. Lau. London: Penguin, 2009.

Muth, Jon J. Zen Shorts. New York: Scholastic Press, 2005.

Muth, Jon J. Zen Ghosts. New York: Scholastic Press, 2010.

Muth, Jon J. Zen Socks. New York: Scholastic Press, 2015.

Author: Matthew Kizior, Career Readiness Teacher

2021